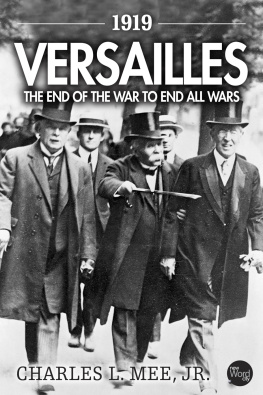

S INCE this book was first published in 1933 we have experienced a Second German War. Before many months have passed we may be faced with the necessity of negotiating a second peace. These negotiations will take place in circumstances of even greater strain and complexity than those which overwhelmed the peacemakers of 1919. The only value which this study of the Paris Peace Conference possesses is that it is an authentic record, although written with the limited vision of a junior official, of the manner in which knowledge and good intentions were swept away by the torrent of events. That torrent, when the time comes to frame the next settlement , will be ten times more formidable; there is no reason to suppose that the wisdom, integrity and endurance of the statesmen and their electorates will be ten times more solid.

The first misfortune of those who went to Paris in 1919 was that they had not foreseen the forces of fear, ambition and selfishness which victory would unleash. They did not realize that the turbulent waters of any post-war world can be contained only by the concrete of rigid principle and the dykes of a firmly enforced programme. They relied upon the wattle of improvisation and a few hastily gathered sods of compromise; these were quickly overrun by the flood.

It may be useful, therefore, in preparing a new edition of Peacemaking1919, to reconsider the conclusions which, ten years ago, seemed so obvious; and to suggest some at least of the lessons which the negotiators of future peace treaties can learn from the errors and misfortunes of their predecessors.

To my mind there are twelve main lessons.

1. Wehavelearntthatthosewhodesiretomakepeacemustfirstunderstandthecausesofwar.

I should like to feel that a group of United States scholars, as upright and as intelligent as those who formed the nucleus of Colonel Houses Enquiry in 1917, were devoting their combined attention to the study and analysis of the several factors which drove an unwilling Europe towards the catastrophe of 1939. Without some such diagnosis we shall be in danger of applying remedies to the symptoms of the illness rather than to its causes. Even in regard to the symptoms there is no general agreement. There are those who attribute the disaster solely to the monomania of Herr Hitler; there are those who throw all the blame upon the pugnacious temperament of the German people; there are those who, in their ignorance, believe that the whole fault lies with the diplomacy of the Great Powers or more specifically with the iniquities of the Treaty of Versailles. The Germans, on the other hand, have been taught to believe that the instigators of the war were the bankers and capitalists of London or New York who are supposed, in a moment of inconceivable aberration, to have plotted their own destruction. Many serious students concentrate upon the economic and social aspects of the malady and trace its origin to inflation, the depression of 1929, and the unemployment problems which were thereby produced. Others again emphasize the demographic aspect, and define as the most important single factor the denial to over-populated countries of an emigration outlet to Australia and the United States. And the determinists take the simplified view that the poor Powers, observing that the rich Powers were showing signs of decay, supposed that their opportunity had come at last.

No single explanation can, however, account for the fact that a world which, by a vast majority, was a pacific world, was plunged against its will into the widest and most intense war in history. Much detached study will be necessary if the several explanations are to be stated in their true order of importance. A mistake in diagnosis is certain to create errors of treatment.

I suggest that in their study of this almost unanswerable problem the new United States Enquiry will derive but scant assistance from the purely political or historical approach; they will find it more useful to bear constantly in mind the analogy of medicine. Wars, like illnesses, are produced not so much by any identifiable infection, as by the action of some bacillus upon an unhealthy organism. The health or ill-health of an organism, moreover is not to be defined in isolated terms, or ascribed solely to the absence or presence of certain factors. It is the combination of varied elements, (conditioned by the temperament, environment, past history and present stage of development of the victim) which renders an organism either subject or immune to the bacillus of war. To diagnose the condition of an individual (even when given the full advantages of time, apparatus and co-operation) is a task requiring immense scientific experience; to diagnose the condition of a nation is a task which may well exceed the capacity of the human brain.

Yet unless we understand the real causes which induced the German people (as distinct from the National Socialist party) to go to war, then we shall not found the future peace upon conditions which shall eliminate from the German body this apparently endemic disease.

2. Afteralongwaritisimpossibletomakeaquickpeace.

The negotiation of a reasonable peace-treaty requires calm and time. Calm is denied to the negotiators owing to the passions aroused by victory after war; time is also denied to them owing to the impatience of their electorates to return to civilian life. However compelling may be the wisdom possessed by the statesmen who negotiate the next peace treaty, the popular pressure to which they will be exposed will be even more embarrassing than that which hampered statesmen at the Paris Peace Conference. The present war is likely to be longer, and has certainly been more atrocious, than that of 191418. On the one hand the desire for retribution, especially in the occupied countries of Europe, will be even more intense than before; on the other hand the clamour for demobilization and a rapid peace is unlikely to be less insistent. The probability that war with Japan will continue after the defeat of Germany will not ease the problem, although it may present it in a different form. The attention of the United States will be diverted away from Europe towards the Pacific: the difficulty of mobilizing large British forces for the Far East will not be diminished if other large British armies have to remain mobilized for garrison duties in central Europe. Yet although the strain of maintaining energy over a wide area will be even greater than before, the need for time will be more essential. We shall be dealing with a Europe racked by hatred, fear, nationalism and hunger. It will take many months of intensive relief work before Europe recovers her sanity. But until she does so, we cannot hope to make a sound or lasting peace.

It will thus be the duty of all responsible people, the duty of Parliament and of the Press, to risk unpopularity by telling the people that they cannot hope to pass in a single night from war to peace. The Armistice will have to be followed by a long and weary period of rehabilitation and reconstruction; peace will have to be created gradually and in different ways in different areas; only after months, perhaps even years, of preparation can the final Congress be assembled. That is a lesson which we must both learn and teach.

3.