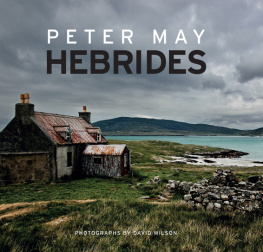

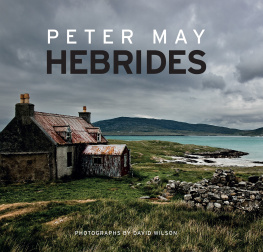

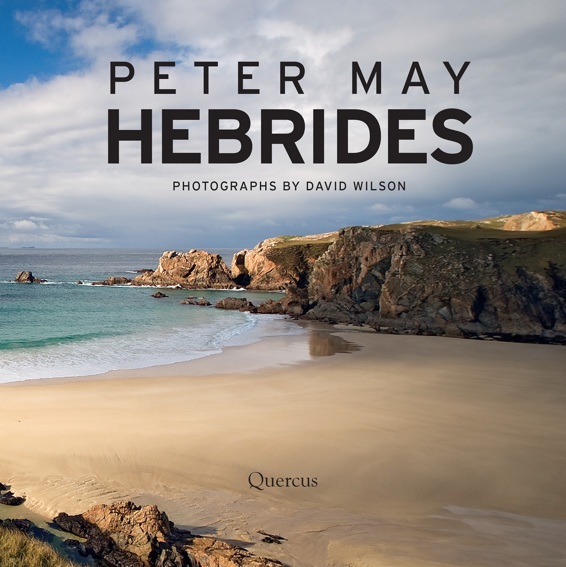

PETER MAY

HEBRIDES

PHOTOGRAPHS BY DAVID WILSON

This book is dedicated to the memory of Lena Kelsall-Boyle

Contents

Tong

This misty dawn over Tong to Tiumpan Head and Point might have looked just like this thousands of years agoexcept for the houses we can see strung along the near horizon.

T his is not an official travelogue taking you on a journey around the tourist high points of the Outer Hebrides. It is a highly personalized account of the islands as I experienced them. Although an outsider, I have lived and breathed these islands as both a television producer filming here in all weathers, and as a novelist whose dark crime thrillers set among them have become bestsellers.

Love them or hate them, once visited these Western Isles will stay with you for the rest of your life.

Dominated by the force of the weather and the power of the Church, they resemble very little to be found on the mainland. As a part of the British experience they are quite unique, and are much further from London and the centers of political power than can be measured in miles alone. Gaelic language and culture prevail, influenced by centuries of Norse occupation. Its music is primal and distinctively Celticfrom the unaccompanied Gaelic psalm-singing that raises goose bumps on the arms, to the haunting Hebridean melodies of Karen Matheson and Capercaillie, Runrig, or Julie Fowlis.

Everyone experiences the Outer Hebrides differently. This is the story of my relationship with the islands: how I first came here, how I spent my time here, and how after a ten-year absence I was drawn back to write the books that would become the most successful of my writing life.

The photographs have been taken by my good friend David Wilson. David was my designer on Machair, the Gaelic-language TV drama that I cocreated and produced. David loved the islands so much that when Machair finished he stayed. He now lives out on the west coast of Lewis and spends his time capturing the magic of the land and seascapes for digital posterity.

I hope that you will join us and enjoy the journey on which Hebrides will take you, and that by the end of it you will have fallen in love with these islands, as I have.

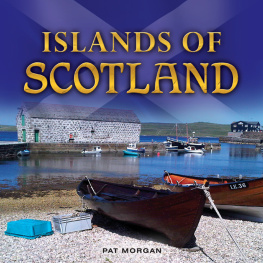

Peter May

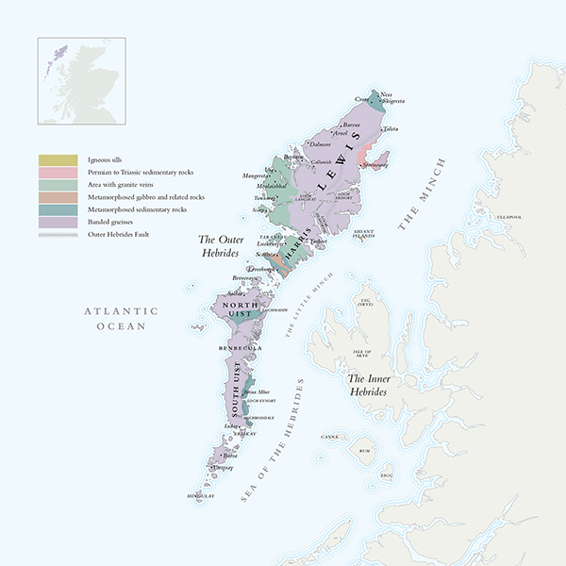

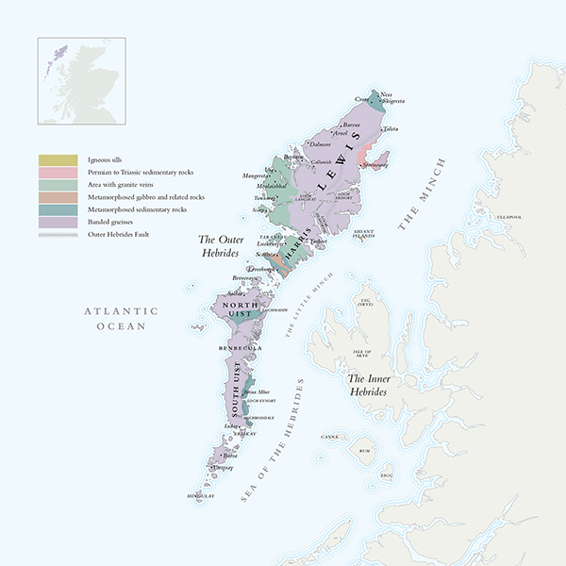

T he Outer Hebrides is a 124-mile- (200 km-) long archipelago off the northwest coast of Scotland. It stretches from Lewis in the north to Berneray in the south, and includes outlying islands such as St. Kilda and the Shiant Isles. The islands vary from the peat-covered uplands of Lewis and the mountains of South Harris, to the wonderful sandy beaches of Barra and the Uists and the breathtaking cliffs of St. Kilda. The spine of the islands was formed by ancient gneisses while the Shiant Isles and St. Kilda are quite young in geological terms, and were created when the Atlantic opened up around 55 million years ago. Since then the Outer Hebrides have been shaped by sea, ice, wind, and rain, to present the starkly beautiful islands we see today.

The Shiants

The Shiant Isles as seen from Lemreway on the east coast of Lewis. They are a comparatively recent geological creation. Beyond them we see the Isle of Skye.

Uig strata

The different rock strata and colors can be seen very clearly here in these outcrops of rock at Uig, southwest Lewis.

Rocks at Dalbeg

The beach at Dalbeg on the west coast of Lewis is littered with giant pebbles that chart the passage of millions of years.

South Uist dawn

Early morning on South Uist could be mistaken for the dawn of time.

The mainland from beyond Tong

The distant snow-covered peaks. of the mainland seen from near Tong, north of Stornoway. Only the houses on the left show the presence of human beings in this timeless landscape.

The mainland from Bayble

This picture has an almost prehistoric feel to it. These are the mountains of the mainland as seen across the Minch from Bayble on the Eye Peninsula.

The geological history of the Outer Hebrides can be read in the rocks and sediments that make up the islands. Their history dates from the Precambrian period more than 525 million years ago, when the Lewisian gneisses were formed, to the Quaternary period, which began around 2.6 million years ago, extending through the last ice age 11,500 years ago to the present day. In between there were major geological upheavals on Earth that changed and formed and shaped the islands. At one point they comprised part of a major landmass, before continents clashed and blocks of the Earths crust moved against each other along the Outer Hebrides fault, throwing up the Caledonian mountains.

Hard to believe, but what later became Scotland once lay close to the equator. Tropical forests grew in low-lying areas, forming the deposits of coal that were later mined in the central belt. As the continents moved, so Scotland drifted north. Its hot, dry climate produced sands and pebbles later forming rocks that can be found near Stornoway today.

At the time of what was known as the Laxfordian Event, 1,700 million years ago, molten rock was forced into the gneisses of South Harris and western Lewis, forming sheets and veins of hard pink granite. And since the granite was less easily eroded than the surrounding gneiss, these developed into the spectacular sea stacks that can now be seen off the coast of Uig.

Sea stacks, Uig

These rock stacks at Uig demonstrate the different rates at which rocks are eroded.

During the Jurassic period floodwaters filled the basin that now forms the Minchthe body of water between the islands and the mainland. It became a shallow sea supporting life of all kinds, and dinosaurs roamed its coasts. Between 23 and 65 million years ago erupting volcanoes along the west coast of Scotland forced molten rock into the layers of sediment in the surrounding seas and formed the magma chambers now exposed as St. Kilda.

Next page