I n his last professional boxing bout in Detroits Olympia Stadium on 11 January 1950, 20-year-old featherweight Berry Gordy Jr outpointed another local fighter, Joe Nelson. Gordy, who was about to serve his country in the Korean War, had established a reputation during his 17-match career as a determined boxer who was willing to take risks to get a result. He had lost three of those 17 bouts but had won 12. It was a record that closely matched his later career in the music industry a career that changed America.

Gordy is a winner, and in the 1960s he showed it by achieving something no one else in American history had managed: he made music that was able consistently to cross the great divide between its African-American birthplace and the mainstream of society. First the USA, then the world clicked fingers, sang along, grooved and danced to the Sound of Young America, as Gordy dubbed his wares. How could they fail to? Motown musics contagious rhythms and irresistible vocal urgings struck a universal chord and, as the US faced up to its Civil Rights responsibilities, made a nonsense of the countrys history of segregation in the popular music charts and society at large.

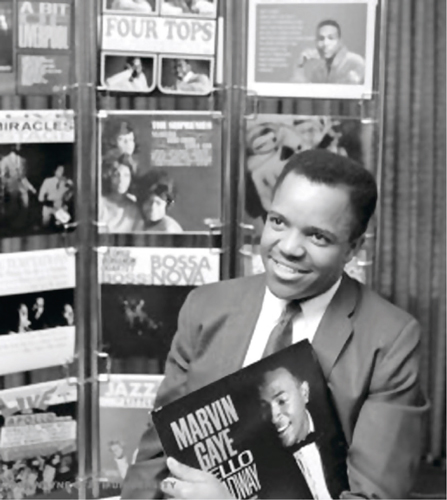

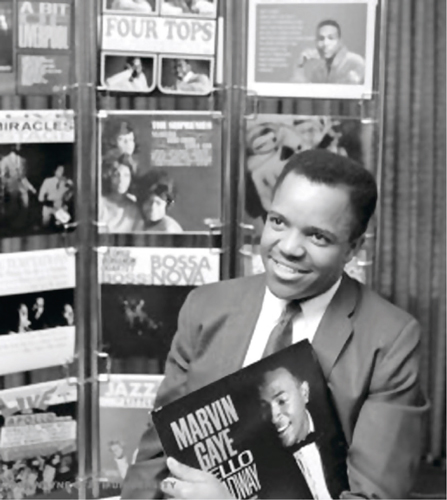

Not that Gordy had any idea of the enormous changes America was about to go through when he borrowed $800 from his family and embarked on his Motown adventure on 12 January 1959. Aside from his boxing career he had worked in the auto industry for which his home town was famous, run a record store and written songs. Hed gained the approval of singer Jackie Wilson and recorded some of his compositions, including the renowned Reet Petite in 1957. Then hed discovered a local group with grand aspirations, the Matadors, and formed a friendship with their leader, William Smokey Robinson.

The Matadors became the Miracles; Robinson listened to Gordys songwriting tips; the latter built a portfolio of R&B artists with whom he wrote and produced. Then Robinson urged Gordy to scratch an itch that had been bothering him for some time and launch a record label: Motown Records. It took a mere nine days for Marv Johnsons Come To Me to be issued on the Tamla label, on 21 January 1959. The next release, featuring Wade Jones, was on the Rayber label, and then the Miracles made their Motown label debut with Bad Girl.

Above:2648 West Grand Boulevard, Detroit, Michigan the base from which Motown disseminated the Sound of Young America until 1972

Above:Berry Gordy invested $800 borrowed from his family to bring about a musical revolution

Motowns first taste of national success came when a song Gordy had co-written, Money (Thats What I Want), was recorded by Barrett Strong and released in August 1959. Initially issued on the Tamla label, it was picked up by Anna Records (started by Gordys sisters Anna and Gwen) and hit number two on the R&B chart and 23 on the Billboard Hot 100. Motown was getting up a head of steam, but Gordy had to wait until September 1960 for the Miracles Shop Around (Tamla) to go all the way to the top of the R&B chart and tantalisingly close to the peak of the pop listings.

By that time Gordy had bought the white-framed house at 2648 West Grand Boulevard that was to be the home of his Motown operation until 1972. Showing typical audacity, he had a sign proclaiming the building as Hitsville USA affixed over the front door a claim whose accuracy was to be proved many times over. The garage was converted into a studio, and it was there that Shop Around and countless other hits were recorded.

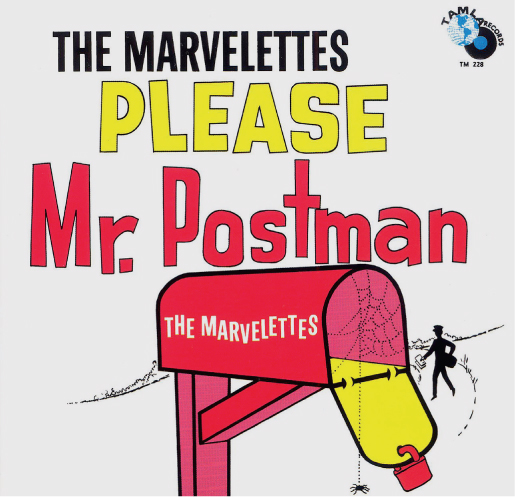

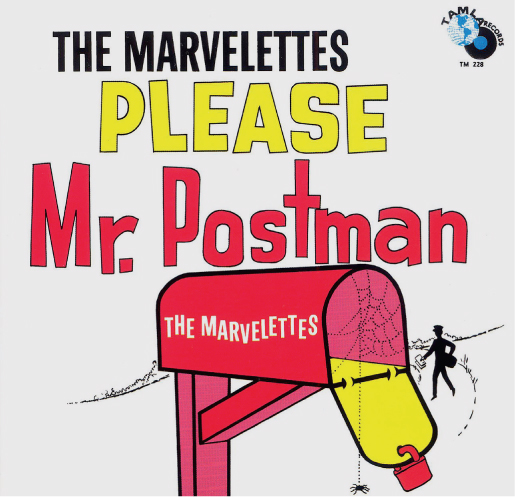

The Motown stable was growing as talented young artists from Detroits working class joined in the race to be the first to reach number one on the pop chart. That honour went to the Marvelettes, whose 1961 song Please Mr Postman had been co-written by a young Brian Holland. Meanwhile, Gordy was busy building Motown into an independent hit factory that would rival and even exceed the output of the huge corporations.

There were whispers in the 60s that he had modelled Motowns slick processes on the assembly lines of Detroits car manufacturers: having found a good product he turned out similar ones, and did it quickly. All the elements of music factory production were there: the in-house songwriting and production units like Robinson and Holland-Dozier-Holland; the house musicians and support singers; the performing geniuses Marvin Gaye, Little Stevie Wonder, Mary Wells, the male and female vocal groups like the Temptations and the Supremes; the weekly quality control meetings.

But however the music was produced, it was fresh and glorious and it was played on millions of transistor radios, making Motown into a phenomenon the like of which the world had never seen and has not seen since. Motown took the rhythms and the call-and-response formats of African-American music forms and transformed them with superb melodies, memorable lyrics, brilliant musicianship, handclaps, wailing singers, blasting horns and driving bass and drums. Where Did Our Love Go, Dancing In The Street, Get Ready, Reach Out hit succeeded hit as the stars illuminated the 60s.

Above:Berry Gordy Boulevard Detroit thoroughfare named after Motowns founding father

Britons took to the Motown sound like ducks to water, getting their fixes on the Tamla-Motown label from 1965 and sometimes making stars of artists who struggled in the States. That label was just one of many that Gordy introduced over the years to spread and diversify his message: Gordy, Miracle, Soul, VIP, Mel-o-dy and Rare Earth were just a few.

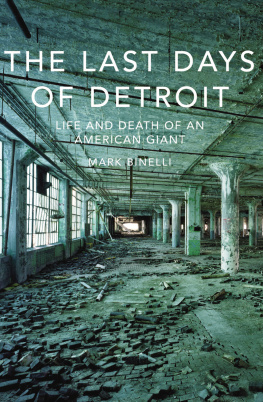

Motown changed; of course it did. Artists and backroom teams came and went, and in 1972 the company aided its expansion into the wider entertainment industry by moving to Los Angeles. The company evolved with the changing times in the 70s and 80s and then, in 1988, Gordy sold his holding in Motown to MCA Records. The label kept producing world-class music, though, even when ownership passed to Polydor in 1994. Nowadays the light is kept burning under the Universal Motown banner.

Above:Please Mr Postman by the Marvelettes the first record from the Motown stable to make it to the top of the US pop chart

Motown celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2009, marking the occasion with a huge reissue exercise that saw much of its stupendous back catalogue introduced to new generations. So the records that got feet moving in the 60s continue to do so.

S tand-up comedian Sinbad discovered sisters LeMisha, Orish and Irish Grinstead singing in the lobby of the Caesars Palace casino in Las Vegas. He sent them to a talent show in Atlanta, Georgia, where Michael Bivins of R&B group New Edition liked what he saw. After their recorded debut, with cousin Amelia Childs, on Subways hit single This Lil Game We Play, Kameelah Williams replaced Amelia. Orish came and went from the group she was to die aged 27 in 2008 but, with the help of Missy Misdemeanour Elliott, work started on the groups first album, No Doubt (1996). The album yielded three hit singles, earned the group a