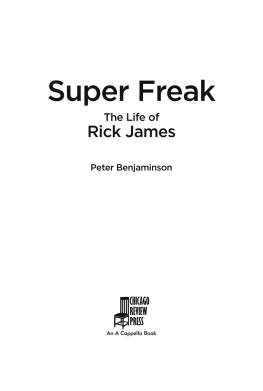

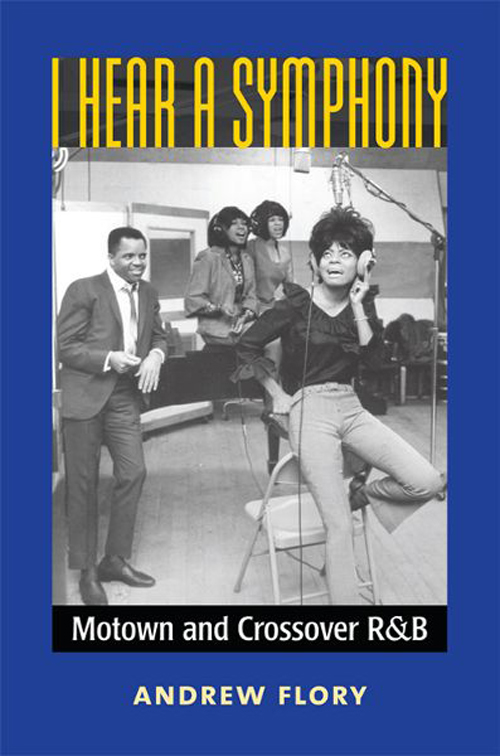

I Hear a Symphony

I Hear a Symphony

Motown and Crossover R&B

Andrew Flory

University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor

Copyright 2017 by Andrew Flory

All rights reserved

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher.

Published in the United States of America by the

University of Michigan Press

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Flory, Andrew.

Title: I hear a symphony : Motown and crossover R&B / Andrew Flory.

Description: Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press, [2017] |

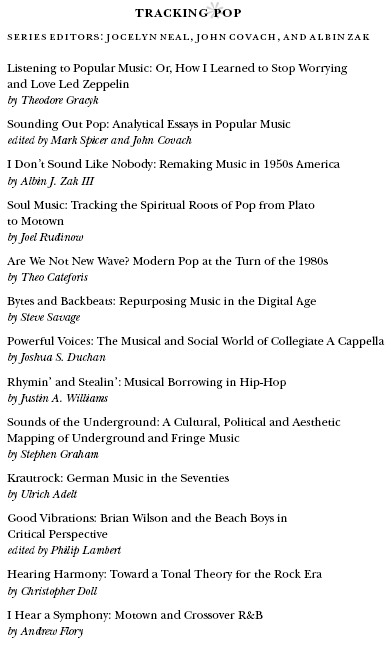

Series: Tracking pop | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017011934| ISBN 9780472036868 (pbk. : alk. paper) |

ISBN 9780472117413 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780472122875 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Motown Record CorporationHistory. | Rhythm and blues musicHistory and criticism.

Classification: LCC ML3792.M67 F56 2017 | DDC 781.64409774/34dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017011934

Thank you to the Dragan Plamenac Endowment of the American Musicological Society, funded in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

Contents

IT SEEMS FITTING to begin by thanking the creative people at Motown. The musicians, songwriters, producers, arrangers, technologists, photographers, business people, and so many others. They made the music. They are the inspiration for the book.

So many people have helped me during my Motown research. Ive been working on Motown projects for more than a decade and the debts add up. On the industry side, Harry Weinger was the greatest asset that any Motown scholar could want. Keith Hughes was constantly available with resources, time, and advice. Andy Skurow always seemed to get me out of a predicament by knowing something that I thought was unknowable. Others who generously gave me materials, provided advice, or shared their stories include Mick Patrick, Eric Charge, Jim Saphin, David Nathan, David Bell, Shelly Berger, Lindsay Farr, Mike McLean, Andrew Morris, George Troia, Mary Johnstone, Salaam Remi, Beatriz Staples, Mickey Gentille, David Ritz, Howard Manheimer, and Amy Gernon.

I studied in a lot of research facilities while writing this book. I cannot imagine undertaking this enterprise without the help of the librarians and staff at the Detroit Public Library, Eastern Michigan University, the Bentley Historical Library, Bowling Green State University, the British Library, Indiana University (Archives of African-American Music and Culture), UNCChapel Hill (Southern Folklife Collection), and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Library and Archives. I could fill a page with all of their names and write another book (or two) with the stories that they helped me to find.

Ive been lucky to work at several fantastic institutions of higher education while working on Motown research projects. The Music Department at UNCChapel Hill was fantastically supportive of my work. I am also thankful to Tracy Fitzsimmons, Bryon Grigsby, Larry Kaptain, and Michael Stepniak at Shenandoah University for giving me a lot of research support. I now work in an unbelievably encouraging environment at Carleton College. My Music Department colleagues deserve great thanks for their conversations, instigations, and advice. They include Larry Archbold, Justin London, Ron Rodman, Melinda Russell, Nikki Melville, Alex Freeman, Hector Valdivia, Lawrence Burnett, Andrea Mazzariello, Megan Sarno, Carole Engel, Diane Frederickson, Susan Shirk, and Holly Streekstra. The Interlibrary Loan specialists Carleton took a lot of extra time to help me track down rare sources. Thanks also to Carletons Hewlett-Mellon Fellowship, Gilman Grant, and Humanities Center and to Dean Bev Nagel and President Steve Pozkanzer for their continued support of my research and teaching.

Ive encountered thousands of students during the last fifteen years. I have been lucky to teach many classes about popular music, and during each my students have helped me to approach my ideas from different perspectives. It has been inspiring to work with a number of very talented and helpful assistants at both Shenandoah and Carleton, including Robbie Taylor, Alan Weiderman, Billy Barry, Miles Campbell, Jen Winshop, Julian Killough-Miller, Matt Jorizzo, Zhilu Zhang, Stella Fritzell, Sookin Lee, Josh Ruebeck, Ben Weiss, Elaine Rock, Lydia Hanson, Cyrus Deloye, Will Richards, and Molly Hildreth.

I am also thankful to a marvelous circle of people who work in academia, whose interests intersect in some way with mine. Whether I see them at conferences, on stage, or in the studio, I would not view music in the same way if it werent for people like John Howland, Phil Ford, Travis Stimeling, Mark Burford, David Brackett, Annie Randall, Mark Clague, Bob Fink, Daniel Groll, Jason Decker, Mike Fuerstein, Joanna Love, Chris Reali, Mark Katz, John Brackett, Jon Hiam, Adam Olson, Walt Everett, Phil Gentry, Theo Cateforis, Mary Simonson, Will Fulton, Pat Rivers, and Brian Wright. Many of these friends provided feedback on portions of this manuscript, and I am very grateful for their time and willingness to help.

Chris Hebert has the calm presence that should be required of all editors. He helped me countless times using a supportive but firm style that is extremely difficult to achieve. John Covach has been my academic mentor for fifteen years. I cannot thank him enough. He encouraged me to pursue Motown studies and brought me to the Tracking Pop series in its earliest days. Albin Zak was also invaluable as a mentor. He guided me through the writing process from beginning to end, read numerous sections of the book multiple times, and always convinced me that I could make it better. Mary Francis, Susan Cronin, Mary Hashman, and Joy Margheim from the University of Michigan Press were extremely helpful at the end of the process.

The Flory and Billings families have been very understanding about my odd hours and seemingly endless amounts of work during vacations and holidays. My three children, Charlotte, Ben, and Alexander, are the loves of my life. I wouldnt get through many of my hardest days without their cheerfulness and energy, and they make the best days even better. I reserve the greatest thanks for my wife, Kate. Without her I would never have had the courage to enter academia and I certainly wouldnt have been able to envision or complete a project like this. I dedicate the book to her.

[Motown] did something that you would have to say on paper is impossible. They took black music and beamed it directly to the white American teenager.

Jerry Wexler

MOTOWN RECORDS was launched in Detroit in 1959 by an African American man named Berry Gordy. It was one of several hundred record companies focused on rhythm and blues (R&B) that opened for business during a steady music industry expansion following the Second World War. R&B was defined by the race of its performers, whose records and live performances relied on outlets catering to a black clientele, such as black appeal radio stations, neighborhood record stores, and public spaces where jukeboxes provided entertainment. Most of the small, independent record companies (indies) that specialized in R&B were able to gain a foothold because they had little competition from major labels. But some of the more ambitious R&B firms reached even farther. Outfits like Atlantic, King, and Specialty were successful in the more lucrative mainstream pop market, which required not only going head to head with the majors but also winning over the larger pop-loving public with unfamiliar musical sounds. This phenomenon of commingling music markets that had once been mostly self-contained was known as crossover. It slowly became more common during the 1950s, setting the stage for a musical and cultural revolution in the years to come.

Next page