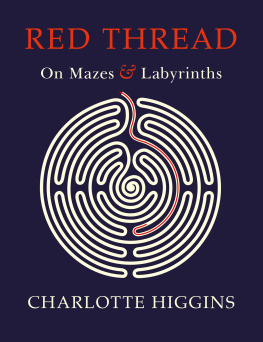

MAZES AND LABYRINTHS

A GENERAL ACCOUNT OF THEIR HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT

BY

W. H. MATTHEWS

1922

Mazes and Labyrinths by W.H. Matthews.

David De Angelis 2017 [all rights are reserved]

CONTENTS

To

ZETA

whose innocent prattlings on the summer sands of Sussex

inspired its conception this book

is most affectionately

dedicated

PREFACE

ADVANTAGES out of all proportion to the importance of the immediate aim in view are apt to accrue whenever an honest endeavour is made to find an answer to one of those awkward questions which are constantly arising from the natural working of a child's mind. It was an endeavour of this kind which formed the nucleus of the inquiries resulting in the following little essay.

It is true that the effort in this case has not led to complete success in so far as that word denotes the formulation of an exact answer to the original question, which, being one of a number evoked by parental experiments in seaside sand-maze construction, was: "Father, who made mazes first of all?" On the other hand, one hesitates to apply so harsh a term as "failure" when bearing in mind the many delightful excursions, rural as well as literary, which have been involved and the alluring vistas of possible future research that have been opened up from time to time in the course of such excursions.

By no means the least of the adventitious benefits enjoyed by the explorer has been the acquisition of a keener sense of appreciation of the labours of the archaeologist, the anthropologist, and other, more special, types of investigator, any one of whom would naturally be far better qualified to discuss the theme under considerationat any rate from the standpoint of his particular branch of learningthan the present author can hope to be.

The special thanks of the writer are due to Professor W. M. Flinders Petrie for permission to make use of his diagram of the conjectural restoration of the Labyrinth of Egypt, Fig. 4, and the view of the shrine of Amenemhat III, Fig. 2 , also for facilities to sketch the Egyptian plaque in his collection which is shown in Fig. 19 and for drawing the writer's attention thereto; to Sir Arthur Evans for the use of his illustrations of double axes and of the Tomb of the Double Axe which appear as Figs. , , and respectively ( Fig. 8 is also based on one of his drawings); to M. Picard (of the Librairie A. Picard ) for leave to reproduce the drawing of the Susa mosaic, Fig. 37 ; to Mr. J. H. Craw, F.S.A. (Scot.), Secretary of the Berwickshire

Naturalists' Club, for the use of the illustrations of sculptured rocks,

Figs. and ; to the Rev. E. A. Irons for the photograph of the Wing maze, Fig. , and to the Rev. G. Yorke for the figure of the Alkborough "Julian's Bower," Fig.

.

The many kind-hearted persons who have earned the gratitude of the writer by acceding to his requests for local information, or by bringing useful references to his notice, will perhaps take no offence if he thanks them collectively, though very heartily, in this place. In most cases where they are not mentioned individually in the text they will be found quoted as authorities in the bibliographical appendix. The present is, however, the most fitting place in which to express a cordial acknowledgment of the assistance rendered by the writer's friend, Mr. G. F. Green, whose skill and experience in the photographic art has been of very great value.

Grateful recognition must also be made of the help and courtesy extended to the writer by the officials of several libraries, museums, and other institutions, notably the British Museum, the Society of Antiquaries, Sion College, and the Royal Horticultural Society. W. H. M.

Ruislip, Middlesex.

1922.

CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION

A DELIGHTFUL air of romance and mystery surrounds the whole subject of Labyrinths and Mazes.

The hedge-maze, which is the only type with which most of us have a first-hand acquaintance, is generally felt to be a survival of a romantic age, even though we esteem its function as nothing higher than that of a playground for children. Many a tender intrigue has been woven around its dark yew alleys. Mr. Compton Mackenzie, for example, introduces it most effectively as a lovers' rendezvous in "The Passionate Elopement," and no doubt the readers of romantic literature will recall other instances of a like nature. The story of fair Rosamond's Bower is one which will leap to the mind in this connection.

This type of maze alone is worth more than a passing thought, but it is far from being the only, or even the most interesting, development of the labyrinth idea.

What is the difference, it may be asked, between a maze and a labyrinth? The answer is, little or none. Some writers seem to prefer to apply the word "maze" to hedgemazes only, using the word "labyrinth" to denote the structures described by the writers of antiquity, or as a general term for any confusing arrangement of paths. Others, again, show a tendency to restrict the application of the term "maze" to cases in which the idea of a puzzle is involved.

It would certainly seem somewhat inappropriate to talk of "the Cretan Maze" or "the Hampton Court Labyrinth," but, generally speaking, we may use the words interchangeably, regarding "maze" as merely the northern equivalent of the classic "labyrinth." Both words have come to signify a complex path of some kind, but when we press for a closer definition we encounter difficulties. We cannot, for instance, say that it is "a tortuous branched path designed to baffle or deceive those who attempt to find the goal to which it leads," for, though that description holds good in some cases, it ignores the many cases in which there is only one path, without branches, and therefore no intent to baffle or mislead, and others again in which there is no definite "goal." We cannot say that it is a winding path "bounded by walls or hedges," for in many instances there are neither walls nor hedges. One of the most famous labyrinths, for example, consisted chiefly of a vast and complicated series of rooms and columns. In fact, we shall find it convenient to leave the question of the definition of the words, and also that of their origin, until we have examined the various examples that exist or are known to have existed.

It may be necessary, here and there, to make reference to various archaeological or antiquarian books and other writings, but the outlook of the general reader, rather than that of the professed student, has been mainly borne in mind.

The object of this book is simply to provide a read-able survey of a subject which, in view of the lure it has exercised throughout many ages and under a variety of forms, has been almost entirely neglected in our literaturethe subject of mazes and labyrinths treated from a general and not a purely archological, horticultural, mathematical, or artistic point of view.

Such references as have been made have therefore been accompanied in most cases by some explanatory or descriptive phrase, a provision which might be considered unnecessary or out of place in a book written for the trained student.

For the benefit of such as may wish to verify, or to investigate more fully, any of the matters dealt with, a classified list of references has been compiled and will be found at the end of the book.

The first summary of any importance to be published in this country on the subject was a paper by the Venerable Edward Trollope, F.S.A., Archdeacon of Stow, which appeared in the

Next page