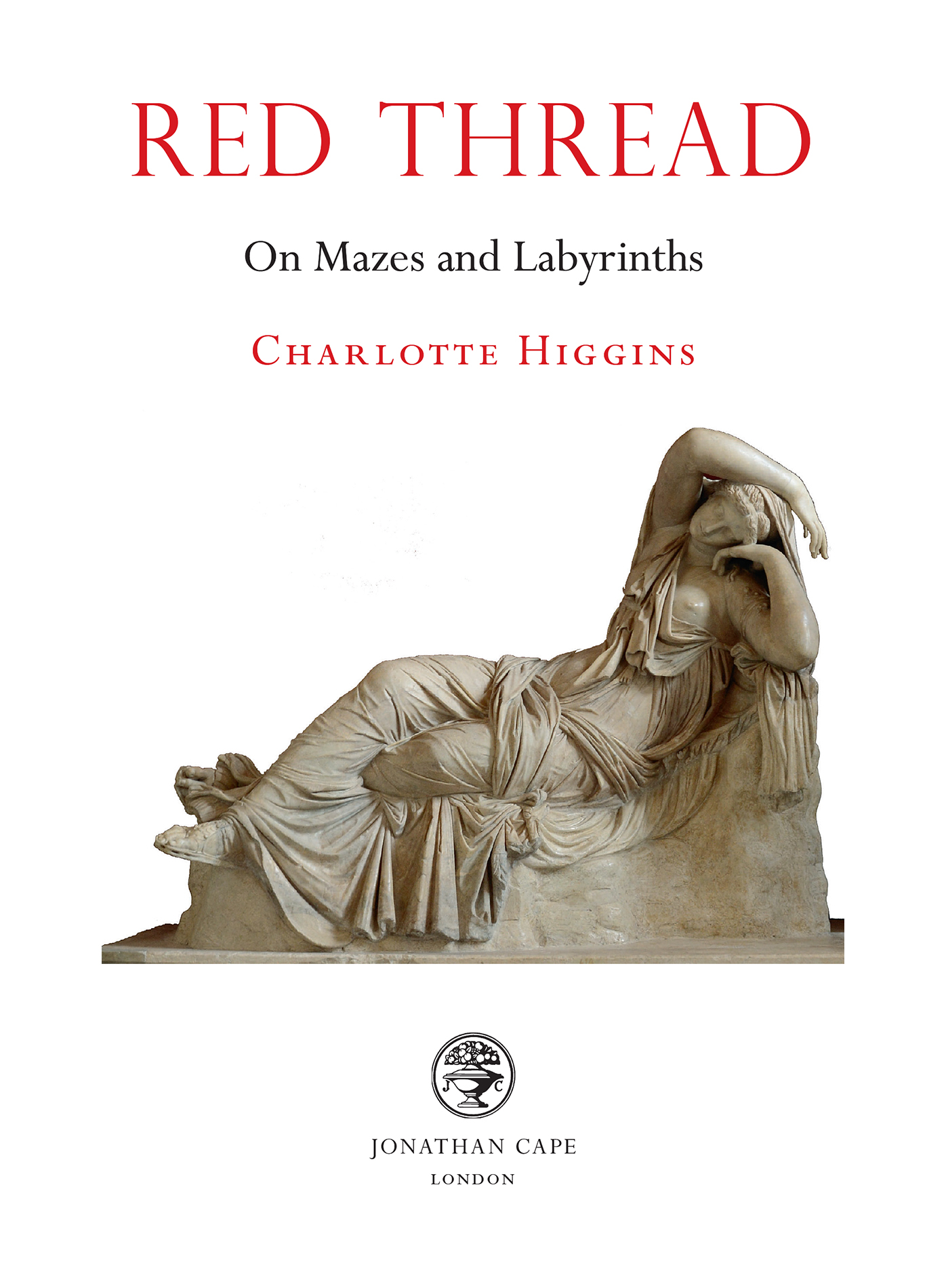

ALSO BY CHARLOTTE HIGGINS

Under Another Sky: Journeys in Roman Britain

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Epub ISBN: 9781473524002

Version 1.0

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

VINTAGE

20 Vauxhall Bridge Road,

London SW1V 2SA

Vintage is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

Copyright Charlotte Higgins 2018

Cover design Suzanne Dean

Charlotte Higgins has asserted her right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

First published by Jonathan Cape in 2018

penguin.co.uk/vintage

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

For Richard Baker

Though of old a Palace, the Labyrinth, of which in spite of clearing and partial reconstitution we have only today a fragment of a fragment, is discontinuous in many directions and in places artificially linked. The visitor who wishes to explore its full circuit still needs the guidance that of old was provided by Ariadnes clew.

Arthur Evans,

foreword to A Handbook to the Palace of Minos at Knossos ,

by John Pendlebury

E UROPA

There was a girl who lived by the sea. She would often wander to a meadow near the waters edge to feel the grass beneath her bare feet, the rush of salt air in her mouth. One day she saw a white bull grazing there. How beautiful he was! His sharp horns gleamed as if some master of the Renaissance had carved and polished them. The girl came cautiously towards him: he took grass from her hand and ate, his brown eyes trusting. She grew bolder and reached out to touch the soft loose pelt on his neck and chest. He let her do it. She picked flowers, wove them into circlets, twined them around his horns. She stroked his shaggy neck and felt his warm whiskery breath on her cheek. She rubbed her face against the silky coat of his broad flank. Eventually he lowered his immense weight to the ground, tucking his front legs beneath him with a clumsy, grunting manoeuvre. She lay down next to him, and he nuzzled her with his soft, damp nose. After a while she wanted to adjust his crown of flowers and so, more and more confident, she straddled his muscled neck, his brawny back, reaching forward to neaten the garland. At that moment, he began to heave himself up. The girl felt herself move with him; she clung on as he jerked to his feet, and then all of a sudden there she was what delight actually riding her tame bull. He ambled through the meadow onto the beach. There, still placid, he lumbered into the softly lapping water. He trod deeper. The girl laughed, and her calves cooled in the chill of seawater.

That was when the bull made an ungainly plunge and shouldered himself right into the sea. The girl felt everything change as his hooves struck free from the sand and he began to swim. There seemed a new purpose in him, a new strength. In an instant they were in the open water. The girl screamed, but there was no one to hear her. She tried to twist off his back, but she was too late: they were so far from the shore, the bull moving with such uncanny speed, that to swim back would be beyond her strength. Instead, she clung on as he moved through the water. Her pink shawl ballooned out behind her like a sail. Bizarre marine creatures surfaced and formed a grinning escort: horse-headed hippocamps and fish-tailed nereids and tritons. A flock of cupids flew above and blew her mocking kisses. When she shrieked at them to help her, they only laughed. After a while she stopped screaming. She even stopped crying. Much, much later, the bull clambered up onto an unfamiliar shore. Exhausted, disoriented, almost paralysed with terror, she slumped off his back onto the sand. Then the bull was gone and in his place a blinding, terrible light, which resolved itself into something like but not quite like a man. He was a god, and she did what he wanted.

Nine months later, the girl, whose name was Europa, had a baby. She named him Minos. He grew up to become the ruler of the island, which was called Crete. Like his father, Zeus, the king of the gods, Minos was famous for his lawgiving and stern justice. His land was prosperous: ninety cities grew up there, which he ruled from a magnificent palace he built at Knossos. His power stretched from the island to the edges of the mainland, and the busy seaways between.

One day Minoss wife, Pasipha, was inspecting the great royal cattle herds. Usually it was a task that she endured rather than enjoyed, but on this occasion her eye was caught by a new beast: a great bull, splendid and handsome, with a glow about him, almost of intelligence, that set him apart from the other creatures. She took an interest in him: she began to go to him regularly, to feed him, groom him. At first her fascination seemed like a harmless diversion. But as the weeks passed, she found herself thinking about him all the time: his power, his animal beauty, his apparently inexhaustible understanding of her loneliness. It came to be that her nights were full of the bull: shed dream about him, imagine doing extraordinary things with him. She was horrified with herself. She tried to put him out of her mind, tried to distract herself with spinning and singing. But the bull was all she could see: the creature had completely invaded her. It was as if shed been possessed by some god; as if she were under a curse.

She went to Daedalus, the artist whom Minos employed at his court. In secret, and with the promise of much gold, she told him what was required. Daedalus responded with sketches, a maquette, a prototype: there was no moral scruple that he could not overcome with his joy in invention. In a hidden part of his workshop he fashioned a hollow simulacrum of a cow. It was so realistic that you would think it lived and breathed it had a heifers velvety fur, liquid eyes that really blinked, and trembling, sensitive nostrils. When Minos was off fighting one of his interminable wars, Pasipha summoned up her courage; she struggled into the cow machine and, carefully operating the mechanical legs as she had been taught by Daedalus, went to the bull.

Later, she had a baby, if you could call it that. Its lower half was boy-shaped, but the neck and shoulders were those of a little black calf. His name was Asterion, but mostly he was known as the Minotaur meaning Minoss bull. He bellowed: all babies bellow. But he never formed words. He grew fast to maturity. After a year, he was a shaggy giant. He loved the wide meadows and the pastures, the cry of the hoopoe and the shadow of the hawk on the grass as it flew for its prey. He delighted to walk among the fields of orchid, of iris, of asphodel. They should have left him to roam the secret wilds, the mountains and the high valleys. He would have come to little harm he might even have been happy if he had found the centaurs in their remote woodland clearings, or the nymphs of the trees and springs, or the fauns and satyrs, the other biformed creatures of nature. But he was a shame and a disgrace to the king a bestial reminder of Pasiphas unnatural desires. Which meant another job for Daedalus.

Next page