InterVarsity Press

P.O. Box 1400, Downers Grove, IL 60515-1426

World Wide Web: www.ivpress.com

Email:

2014 by Travis Scholl

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from InterVarsity Press.

InterVarsity Press is the book-publishing division of InterVarsity Christian Fellowship/USA, a movement of students and faculty active on campus at hundreds of universities, colleges and schools of nursing in the United States of America, and a member movement of the International Fellowship of Evangelical Students. For information about local and regional activities, visit intervarsity.org .

Scripture quotations, unless otherwise noted, are from the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

While all stories in this book are true, some names and identifying information in this book have been changed to protect the privacy of the individuals involved.

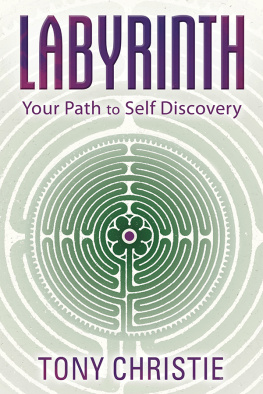

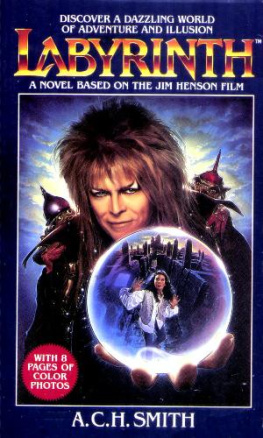

Labyrinth photo on p. 16: Dan Gill

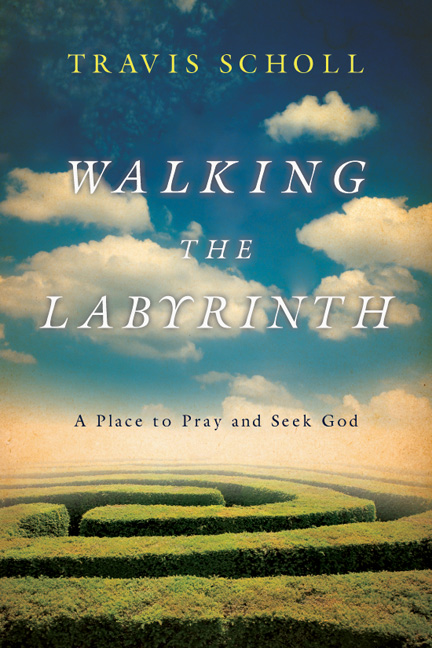

Cover design: Cindy Kiple

Images: maze landscape: James Thew/ Fotolia.com

old paper background: Kontrec/iStockphoto

ISBN 978-0-8308-9593-9 (digital)

ISBN 978-0-8308-3583-6 (print)

For Jenny

If the labyrinth is life, we walk it together.

I thought of a labyrinth of labyrinths, of one sinuous spreading labyrinth that would encompass the past and the future and in some way involve the stars.

JORGE LUIS BORGES THE GARDEN OF FORKING PATHS

He was in the wilderness forty days.

MARK 1:13

Foreword

T RAVIS SCHOLL WINDS HIS WALK through the one labyrinth and all the labyrinths in the company of St. Mark. I cant think of a better companionexcept that you come toonor a wiser choice.

We end in the infinities. We end where we began.

This is the pattern of Marks Gospel. Let me explain. In the smack beginning of his ministry, Jesus came to Galilee. I dont believe this is merely a historical choice. In fact I think Mark knew already that he would end the story with much the same words. The white-robed man sitting in the empty tomb tells the women: He has been raised; he is not here. But go, tell his disciples and Peter that he is going ahead of you to Galilee; there you will see him, just as he told you.

Mark does not end, as do all the other Gospels, with a sense of completion: a final commission in Matthew, an ascension in Luke and John. In fact, given that promise that the disciples will meet him in Galilee (if we accept the scholars conviction that the Gospel cuts off at 16:8), Mark seems to have no ending at all. We end where we began, in Galilee! Why? Because Mark does not believe the story has an end. Having finished one reading, he wants us to read the whole story againbut this time in the light of the resurrection! And again, Jesus will walk ahead of them to Jerusalem. Over and over and over.

Travis Scholls labyrinth is exactly like that! A walk with Jesus to be taken over and over and over.

But each new walk changes his labyrinth a little from the last because he uses personal experience throughout. Scholls varying moods, his fears, his sorrows, his delights, constantly make each round new.

And so it should be for you who will read his book.

Once you have finished reading of labyrinths heaped on labyrinths, read it again, only this time read it seeking your own experiences!

This is the way of all personal devotions.

Walt Wangerin Jr.

part one

Before the Beginning

On Ash Wednesday, in the year of our Lord 2011, I began walking the labyrinth.

I have been walking it ever since.

I came upon the labyrinth by accident. In 2008, my wife and I moved into our home in St. Louis, Missouri, returning to our hometown after living in Connecticut for a while. Getting to know the neighborhood, I was walking past a church near our house, First Presbyterian Church, which sits at the dead-end of Midland into Delmar Avenue. Glancing at the churchyard, I discerned thin circles of cobblestone brick enmeshed in the grass.

I walked closer and recognized its circular pattern. I had heard and read about labyrinths before. And ever since college, I had read and reread the Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges (18991986), the writer whose paradoxical fictions are labyrinths, like M. C. Escher sketching with words. Now I stood at the literal foot of its infinite path. Its open entrance invited me.

I began to walk.

After that first discovery, I would walk its path occasionally, as the mood struck. For all I know, I am this labyrinths only pilgrim. I have never noticed anyone else walking it.

The labyrinth first intrigued me as a leisurely curiosity. But then came the questions: Why walk a labyrinth anyway? What am I supposed to do as I walk it?

Walking the labyrinthany labyrinthis a curious thing. The labyrinth is a distinctive kind of maze. Its purpose is singular, as is its path. Thus it isnt the kind of game we typically think of when envisioning a maze, hoping we make the right choices to reach the end.

As a matter of fact, a labyrinth does not have an end per se. It has a center. And as long as you follow the path, you will reach the center. Every time. So there is a kind of mindlessness to the labyrinth.

But I soon discovered a purpose in the mindlessness. The labyrinth, paradoxically, stirs up a new kind of mindfulness, an awareness of the path that opens its pilgrims into a deeper sense of their surroundings, the lifeworldshome, neighborhood, work, family, friendships, ad infinitumin which they find themselves.

In short, the path of the labyrinth is the process of discovery. Its path is process itself. I walk the labyrinth to discover anew the worlds I inhabit. I walk it to discover what I thought was previously undiscoverable, what I didnt even know was there. Which is why I can walk the same labyrinthtime and againand still find the path new.

What started as leisure was now turning to discipline. And the path is always new, because, as a spiritual discipline, the labyrinth is a path of contemplation, reflection, prayer.

On the surface of it, it is a place for silence and for speaking into silence, for speaking to One unseen. But beneath the surface, walking the labyrinth is a profound discipline in listening, in active silence, in finding movement and rhythm in the stillnesses underneath and in between every days noise. Walking the labyrinth is an exercise in finding the voice speaking in whispers underneath the whirlwind of sound.

And yet beneath the silence, the labyrinth tells a story, a history.

Here is its beginning: Daedalus, the ancient Greek father of architects, built the mythical first labyrinth, step by treacherous step. At its center sat confined the grotesque half-man, half-bull named Minotaur, for whom it was built as a prison. As the story is told, Daedalus built the prison-maze with such intricate cunning that he nearly trapped himself within its circuits.

It would be awhile later, as Ovid tells it in his Metamorphoses, that the warrior Theseus would be forced to brave the labyrinth to kill the Minotaur. To keep from losing his own way, Theseus held in his hand a clue of thread, its thin, lustrous strand falling behind him to mark the path. The end of the thread was held in the hand of a companion waiting at the entrance.