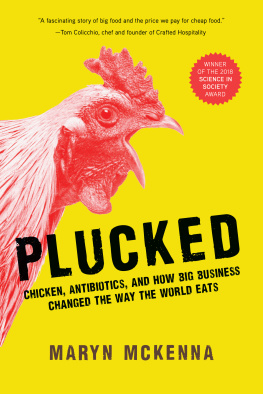

SUPERBUG

THE FATAL MENACE OF MRSA

MARYN MCKENNA

FREE PRESS

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2010 by Maryn McKenna

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof

in any form whatsoever. For information address Free Press Subsidiary Rights Department,

1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

First Free Press hardcover edition March 2010

FREE PRESS and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases,

please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949

or business@simonandschuster.com.

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event.

For more information or to book an event contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau

at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com .

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

McKenna, Maryn.

Superbug : the fatal menace of MRSA / Maryn McKenna1st Free Press hardcover ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Staphylococcus aureus infections. 2. Methicillin resistance.

I. Title. [DNLM: 1. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureusUnited States.

2. Health PolicyUnited States. 3. History, 20th CenturyUnited States.

4. History, 21st CenturyUnited States. WC 250 M478s 2010]

QR201.S68M45 2010

616.9297dc22 2009037793

ISBN 978-1-4165-5727-2

ISBN 978-1-4391-7183-7 (ebook)

For Loren

Everybody knows that pestilences have a way of recurring in the world; yet somehow we find it hard to believe in ones that crash down on our heads from a blue sky. There have been as many plagues as wars in history; yet always plagues and wars take people equally by surprise.

ALBERT CAMUS, The Plague

CONTENTS

AUTHORS NOTE

I first became aware of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, MRSA, in 2003, when I shadowed a group of epidemiologists from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Los Angeles Department of Public Health through an outbreak investigation. Disease detection was not new to me: I was the CDC beat reporter for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, and my job was to chase the CDC as it chased epidemics around the world. My newsroom colleagues jokingly called me Scary Disease Girl.

The Los Angeles outbreak, though, was not so much frightening as it was puzzling. Serious MRSA skin infections were appearing in gay men who frequented sex clubs. The task facing the disease detectives was finding out whether the bug was behaving as it always had, passing between people who had contact with each others skin, or with surfaces such as benches that skin had recently touched, or whether it had taken on the characteristics of a sexually transmitted disease. It was an intriguing outbreak, full of questions about policy and publicity, sexual behavior and bacterial unpredictability, and I marked it down mentally as interesting and moved on. (The verdict, in the end: skin-to-skin and skin-to-surface contact, no different from a gym.)

Fast-forward three years, and I had left my newspaper job and was studying for twelve months in the media fellowship program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, investigating overcrowding and stress in emergency rooms. I spent eight overnight shifts a month in ERs in several cities. In every city, MRSA was everywhere I looked. Patients had minor skin infections, huge gaping wounds, grave infestations of bone and muscle, and critical pneumonias that got them whisked immediately to the ICU. I cannot forget one man who unbuttoned the cuffs of a crisply creased dress shirt to reveal that he had wrapped both forearms in hand-towelsbecause bandages were not sufficient to contain the seepage from infections that had eaten through his skin and deep into muscle, exposing the white flash of tendons in the open pit of his elbow. I was horrified. This was much more serious than boils from a gym bench. But the attending physician I was shadowing that night, though compassionate, was otherwise unimpressed, because he saw some form of MRSA infection, usually many MRSA infections, on most nights of the week.

A year later, I wrote a story for Self magazine about the unappreciated threat that community-associated MRSA posed to women and childrenunappreciated because, at the time, coverage of MRSA in most of the press was limited to reports of outbreaks in prisoners and sports teams, which is to say, men. If I needed a measure of how much MRSAs incidence had changed since my first encounter with the bug, the reaction to that 2007 story gave it to me. Almost one hundred women, and a number of men as well, emailed me, called me, or wrote me anguished letters about how MRSA had disrupted their families and drained their bank accounts. Shortly afterward, I began publishing a blog to gather MRSA stories, also called Superbug. It has been running for more than two years now, and in that time, not a week has gone by but someone has contacted me unprompted because they need to describe how MRSA has shattered their lives.

For most of my career as a reporter, I took pleasure in being a disease geek talking to other disease geeks, telling stories that combined the surprises of biology and the intricacies of epidemiology with a faint frisson of fear. But when I examined my professional life, I realized that many of the outbreaks I drew my readers into were caused by diseases that may have fascinated them, but did not imminently threaten them. When I contemplated how MRSA advanced while I was not paying attention, I felt as though I had been telling my readers to stare up at the mountains for fear one of them might one day fall on us, while all the time a flood was rising unnoticed around our feet.

MRSA is that flood. It is a crisis in many dimensions. Its advance exposes huge gulfs between medical researchers and health care workers, between health care and public health, between public health and the public it is intended to serve. It illustrates failures of science, failures of the marketplace, and failures of support for research and innovation. It touches the way we fund our schools and schedule our work lives, and it demonstrates that the way we raise food animals is not sustainable or safe.

As Superbug shows, the history of MRSA is the history of three overlapping epidemics: in hospitals, in everyday life, and now in animals. We could have responded to each as they occurredwhen our toes were wet, or our ankles. We failed. Now the flood is somewhere around our knees, and rising.

Maryn McKenna

Minneapolis, 2009

SUPERBUG

CHAPTER 1

THE FIRST ALERT

Tony Loves knee ached.

The rangy, round-headed thirteen-year-old had banged into a friend a week ago while they were playing volleyball in the school gym. They crashed to the floor together, arms and untied shoelaces flying, and Tony scraped his elbow. After school, he and his mother and his grandmother had bandaged the cut and shrugged it off. He was a teenager, after all; Clarissa Love, his mother, expected her son to be rambunctious. It was mid-September 2007. The weather was still hot south of Chicago and Tony was still in summer mode, twitching behind his desk at school until the bell rang and he could burst out and work it off. The scratch was no big deal, and Tony was tough; he was the second child of six, and the only boy until his baby brother, the youngest, had come along. Tony saw himself as the man of the family, keeping his sisters in line while Clarissa, who was thirty, worked as an aide for the disabled.

Next page