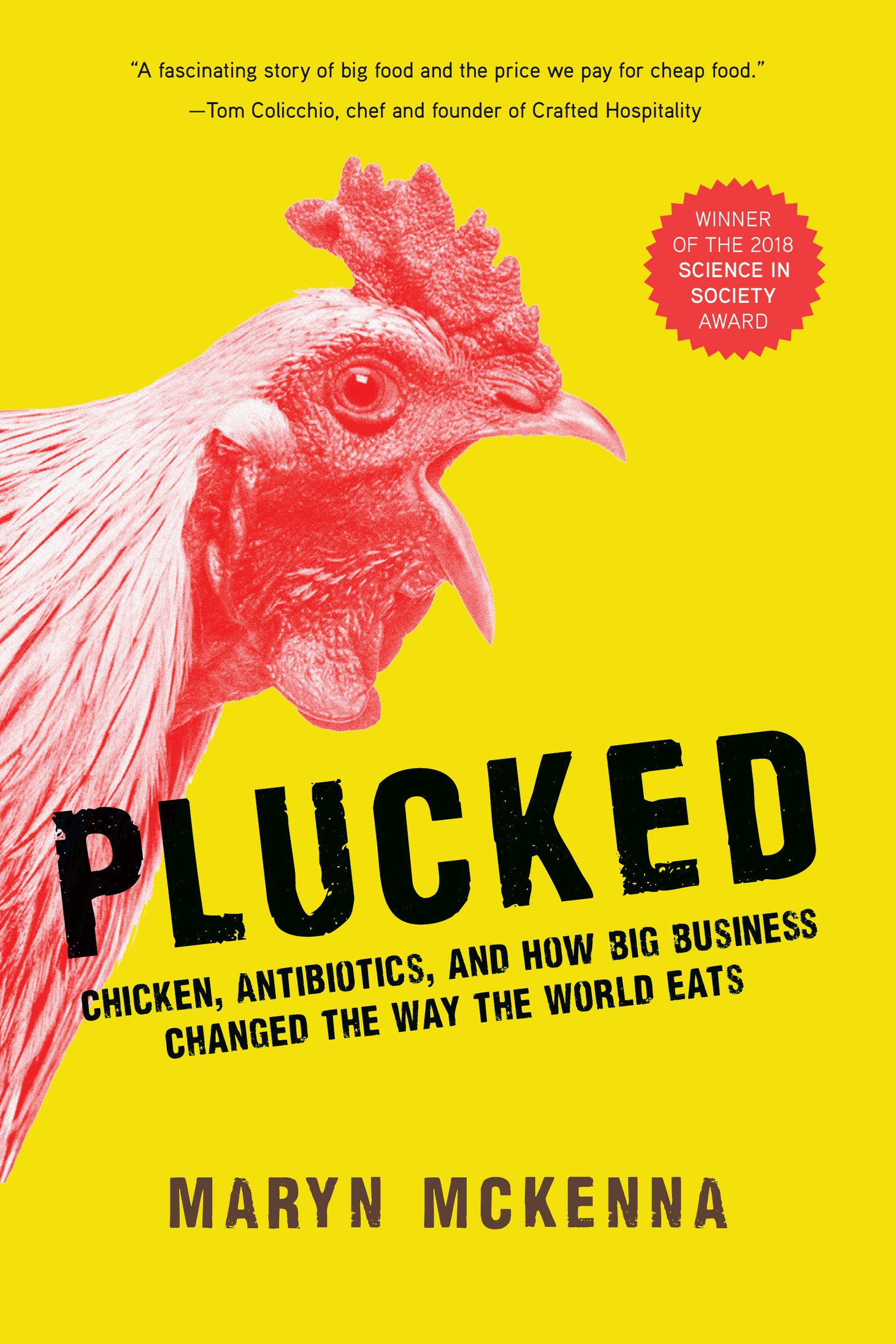

PRAISE FOR PLUCKED:

Maryn McKennas enthralling book is ostensibly about chicken but is really about us: the foolish choices we have made and the happier, healthier future that awaits if we liberate this most American of foods from the drug fix we have imposed on it.

Dan Fagin, author of the Pulitzer Prizewinning Toms River

Every now and then I read a book that I believe holds the power to radically remake the world for the better. [This] is just such a book.

Anna Lapp, author of Diet for a Hot Planet

Maryn McKenna is the leading journalist worldwide on antibiotic overuse and resistance. In [this book] she tells a crucial part of that story: the vast misuse and overuse of antibiotics in industrial farming.

This clear, urgent explanation of how we got here and whats at risk should be required reading for anyone who wants to see change happen.

Lance B. Price, Ph.D., founder and director of the Antibiotic Resistance Action Center

Always curious, never pedantic, Maryn McKenna shows empathy for man and sympathy for fowl, while giving voice to scientists and farmers who have concluded that antibiotic-drugged chickens imperil the American diet. [This book] is beautifully written, rendering her research and the agitations of reformers all that more persuasive.

John T. Edge, author of The Potlikker Papers

Maryn McKenna is one of the best journalists in America reporting on public healthThis important book is a must-read for anyone wanting to understand why our approach to producing food is unsustainable and the changes we must make if we dont want to return to a pre-antibiotic era.

Richard E. Besser, M.D., president and CEO of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

A must-read for anyone who cares about the quality of food and the welfare of animals.

Mark Bittman, author of How to Cook Everything

Published by National Geographic Partners, LLC

1145 17th Street NW Washington, DC 20036

Copyright 2019 Maryn McKenna. All rights reserved. Reproduction of the whole or any part of the contents without written permission from the publisher is prohibited.

Previously released in hardcover as BIG CHICKEN: THE INCREDIBLE STORY OF HOW ANTIBIOTICS CREATED MODERN AGRICULTURE AND CHANGED THE WAY THE WORLD EATS Copyright 2017 Maryn McKenna.

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC and Yellow Border Design are trademarks of the National Geographic Society, used under license.

ISBN: 978-1-4262-1962-7

Ebook ISBN9781426221217

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows:

Names: McKenna, Maryn.

Title: Big chicken : the incredible story of how antibiotics created modern agriculture and changed the way the world eats / Maryn McKenna.

Description: Washington, D.C. : National Geographic, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017011586 | ISBN 9781426217661 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Antibiotics in animal nutrition. | Drug resistance in microorganisms. | ChickensMicrobiology. | PoultryMarketing. | ChickensMarketing.

Classification: LCC SF98.A5 M35 2017 | DDC 636.5/0895329dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017011586

Since 1888, the National Geographic Society has funded more than 13,000 research, exploration, and preservation projects around the world. National Geographic Partners distributes a portion of the funds it receives from your purchase to National Geographic Society to support programs including the conservation of animals and their habitats.

Become a member of National Geographic and activate your benefits today at natgeo.com/jointoday.

For rights or permissions inquiries, please contact National Geographic Books Subsidiary Rights:

Interior design: Katie Olsen

19/VP-CG/1

v5.4

a

For Bob Lauder

On this earth there are plagues and there are victims, and its up to us, as much as possible, not to join forces with the plagues.

Albert Camus, The Plague, 1947

I think any industry producing meat for almost the price of bread has got a big future.

Henry Saglio, to the U.S. House of Representatives, 1957

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

EVERY YEAR I SPEND SOME TIME in a tiny apartment in Paris, seven stories above the mayors offices of the 11th arrondissement. The Place de la Bastillethe spot where the French Revolution sparked political change that transformed the worldis a 10-minute walk down a narrow street that threads between student nightclubs and Chinese fabric wholesalers. Twice a week, hundreds of Parisians crowd down it, heading to the march de la Bastille, stretched out along the center island of the Boulevard Richard Lenoir.

Blocks before you reach the market, you can hear it: a low hum of argument and chatter, punctuated by dollies thumping over the curbstones and vendors shouting deals. But even before you hear it, you can smell it: the funk of bruised cabbage leaves underfoot, the sharp sweetness of fruit sliced open for samples, the iodine tang of seaweed propping up rafts of scallops in broad rose-colored shells. Threaded through them is one aroma that I wait for. Burnished and herbal, salty and slightly burned, it has so much heft that it feels physical, like an arm slid around your shoulders to urge you to move a little faster. It leads to a tented booth in the middle of the market and a line of customers that wraps around the tent poles and trails down the market alley, tangling with the crowd in front of the flower seller.

In the middle of the booth is a closet-size metal cabinet, propped up on iron wheels and bricks. Inside the cabinet, flattened chickens are speared on rotisserie bars that have been turning since before dawn. Every few minutes, one of the workers detaches a bar, slides off its dripping bronze contents, slips the chickens into flat foil-lined bags, and hands them to the customers who have persisted to the head of the line. I can barely wait to get my chicken home.

The skin of a poulet crapaudinenamed because its spatchcocked outline resembles a crapaud, a toadshatters like mica; the flesh underneath, basted for hours by the birds dripping onto it from above, is pillowy but springy, imbued to the bone with pepper and thyme. The first time I ate it, I was stunned into happy silence, too intoxicated by the experience to process why it felt so new. The second time, I was delighted againand then, afterward, sulky and sad.

I had eaten chicken all my life: in my grandmothers kitchen in Brooklyn, in my parents house in Houston, in a college dining hall, friends apartments, restaurants and fast-food places, trendy bars in cities and old-school joints on back roads in the South. I thought I roasted a chicken pretty well myself. But none of them were ever like this, mineral and lush and direct. I thought of the chickens Id grown up eating. They tasted like whatever the cook added to them: canned soup in my grandmothers fricassee, her party dish; soy sauce and sesame in the stir-fries my college housemate brought from her aunts restaurant; lemon juice when my mother worried about my fathers blood pressure and banned salt from the house. This French chicken tasted like muscle and blood and exercise and the outdoors. It tasted like something that it was too easy to pretend it was not: like an animal, like a living thing.