Contents

Guide

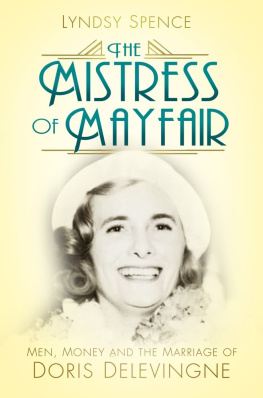

Playboys and Mayfair Men

Playboys and Mayfair Men

CRIME, CLASS, MASCULINITY, AND FASCISM IN 1930s LONDON

Angus McLaren

Johns Hopkins University Press / Baltimore

2017 Johns Hopkins University Press

All rights reserved. Published 2017

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Johns Hopkins University Press

2715 North Charles Street

Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363

www.press.jhu.edu

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: McLaren, Angus, author.

Title: Playboys and Mayfair men : crime, class, masculinity, and

fascism in 1930s London / Angus McLaren.

Description: Baltimore, Maryland : Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017004265 | ISBN 9781421423470 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781421423487 (electronic) | ISBN 1421423472 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 1421423480 (electronic)

Subjects: LCSH: RobberyEnglandLondonCase studies. | Violent crimesEnglandLondonCase studies. | CriminalsEnglandLondonCase studies. | Social classes EnglandLondonHistory20th century. | London (England)Social conditions20th century.

Classification: LCC HV6665.G72 M35 2017 | DDC 364.15/5209421dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017004265

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

Special discounts are available for bulk purchases of this book. For more information, please contact Special Sales at 410 -- 6936 or specialsales@press.jhu.edu.

Johns Hopkins University Press uses environmentally friendly book materials, including recycled text paper that is composed of at least 30 percent post-consumer waste, whenever possible.

Contents

Acknowledgments

When I first came across newspaper accounts of the Hyde Park Hotel robbery, I was puzzled to read that the villains had attacked their victim with a life preserver. For Americans a life preserver (or life jacket) is a flotation device. My difficulty in understanding what the papers meant by the phrase proved once more the truth of the line (often attributed to George Bernard Shaw) The English and the Americans are two peoples divided by a common language. I soon discovered a life preserver in 1930s Britain was a truncheon, or what North Americans would call a blackjack. Helpfully, the Oxford English Dictionary notes that Anthony Trollope and Arthur Conan Doyle often used the term. The life preserver (cudgel, baton, truncheon, cosh, nightstick, or bludgeon) was a short club, heavily loaded with a lead weight at one end and a strap or lanyard at the other. Easily concealed, it was purportedly designed for self-defense, hence the name life preserver. A single forceful blow could cause concussion and even prove fatal. The type of weapon used in the Hyde Park Hotel robbery was of scant legal importance. Nevertheless my stumbling over the curious term life preserver pricked my curiosity and drew me to the case. And as I tracked the jewel thieves through police reports and press accounts, I realized, to my surprise and excitement, that an investigation of the public response to their misdeeds offered a fresh perspective on many aspects of 1930s British society.

But should I devote a book-length study to the misdeeds of wastrels and scoundrels? George Orwell, who warned that the author was besmirched by the material he handled, might well have viewed even the desire to launch such a project as betraying a kind of spiritual inadequacy. were more understanding. Taking time out of their busy schedules, Lucy Bland, Stephen Brooke, Brian Dippie, Jack Little, and Nikki Strong-Boag read early versions of the entire manuscript. Adrian Bingham shared his unrivaled knowledge of the interwar press. I owe special thanks to Robert Nye. He not only read several drafts, but his enthusiastic support of the study also lifted my spirits when, like many authors, I reached that stage of wondering whether the project made any sense at all. I am also grateful to Judith Allen, Peter Bailey, Paul Delany, Catherine Ellis, Michael Finn, Matt Houlbrook, Jim Kempling, Kathy Mezei, Tom Saunders, and Tim Travers for peppering me with ideas and suggestions. Terence Greer offered to help with the cover illustration. More contributions came from Susannah and Richard Taffler and Aime and Michael Birnbaum, who were, in addition, wonderful hosts during my repeated stays in London.

I owe much to the helpful staffs of the National Archives, the Archives of Kent State University, Wellington College Archives, Harrow School Archives, Oundle School Archives, the libraries at the University of Victoria, the University of British Columbia and Simon Fraser University, and the British Library. Jaimee McRoberts at the British Library News Room was particularly considerate. Willi Lauri Ahonen generously translated a Finnish passage for me; Tineke Hellwig and Dick Unger did the same from the Dutch. Jill Ainsley was an imaginative and industrious research assistant, and at the University of Victoria, Karen Hickton has been an ever-helpful departmental secretary. My previous books were all supported by the Social Science and Research Council of Canada, which allowed me to make several overseas research trips. I am happy to acknowledge once more the Councils crucial role in generously encouraging historical research. This study was launched with the funds left over from my last major grant.

And finally, no words can adequately express all that I owe to Arlene, who has supported me in so many ways. One trifling example: Im embarrassed to think of the number of times I have interrupted her in the midst of writing or reading to share with her yet another anecdote relating to playboys or Mayfair men. She not only tolerates these countless intrusions and hears me out; she often has a better notion than I do as to how such material could be most effectively used. It is due to her aversion to the use of the strained or artificial that I do not conclude these acknowledgmentsas I had first plannedby lauding her as my life preserver.

So Orwell said of Cyril Connolly for writing The Rock Pool (1936). See George Orwell: An Age Like This: 19201940 , in The Collected Essays, Journalism, and Letters of George Orwell , ed. Sonia Orwell and Ian Angus (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1968), 1:226.

INTRODUCTION

In the spring of 1938 the English author Fryniwyd Tennyson Jesse wrote to her friend Grace Burke Hubble, the wife of the American astronomer Edwin Hubble: I do not know whether the respectable newspaper which I am sure you and Edwin take, had an account of the trial over here known as the trial of the Mayfair men. Anyway I went to it. It was not an important trial but very interesting as a social phenomenon. London society found the trial of the Mayfair men or the Mayfair playboys (as they were often called) absolutely riveting. Four young men in their twenties, all products of elite English public schools, and respectable families, had conspired to lure to the luxurious Hyde Park Hotel a representative of Cartier, the famous jewelry firm. There they brutally bludgeoned him and then made off with eight diamond rings that today would be worth approximately half a million pounds. Such well-connected young people were not supposed to appear in the prisoners dock at the Old Bailey. Not surprisingly, the popular newspapers had a field day in responding to the publics appetite for information on the accuseds pasts, their friends, and families. The trial is fascinating, and not simply for what it tells us about four young mens loutish behavior; the contemporary press and public of the 1930s saw that this court case revealed aspects of class, gender, politics, crime, and punishment that had otherwise escaped serious scrutiny.