I NTRODUCTION

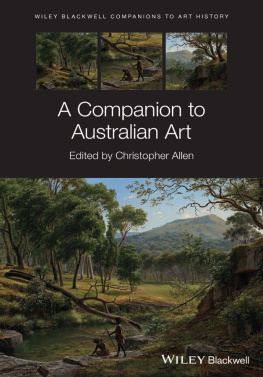

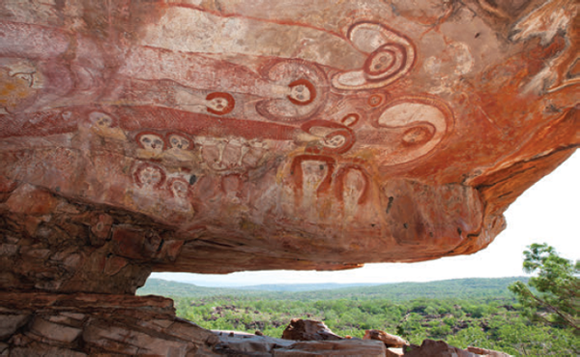

N OT LONG AGO Western interest in Indigenous Australian art was largely confined to archaeologists and anthropologists who saw in its antiquity the origins of human culture. Anthropologists were spurred by the last chance to study what they believed were the final remnants of an ancient Stone Age society before it disappeared into the onrush of modernity. Archaeological investigations of rock art continue apace, but anthropologists, regretting the error of their ways, now study Indigenous art as a living modern culture.

Towards the end of the twentieth century the Western artworld entered the fray, though its interest had a considerable prehistory. In the latter half of the nineteenth century a few enthusiasts began to acknowledge the aesthetic qualities of Indigenous Australian art. In the years after the First World War a handful of modernist artists and designers made it a cause in their efforts to develop a distinctive Australian modern art, but it wasnt widely valued until after the Second World War. Even then it was classified as primitive art, with art historians and critics deferring to anthropologists. Art historians only became seriously interested in the 1980s, when the art was moved upmarket to the bright lights of the contemporary art scene. While the artworlds focus has been on contemporary Indigenous art, once swept into the artworld it was also carried into the history of art.

Anthropologists have either written or heavily influenced all accounts of Indigenous Australian art, including considerable recent scholarship on regional art practices for example Hetti Perkinss (b. 1965) exhibition Crossing Country and three general overviews.

The crucial starting point of this book is that Indigenous art has a modern history; it is one of many modernisms produced from modernitys global reach. If Ernst Gombrich is our guide, in Australia modern art began a year earlier than in Europe. The really modern times, said Gombrich in 1964, announce the break in tradition: it dawned when the French Revolution of 1789 put an end to so many assumptions that had been taken for granted for hundreds, if not thousands of years. Gombrich had in mind the European experience, but Aborigines living around Sydney harbour faced a much more profound break in the assumptions of their civilization when the revolution of 1788 exploded on their shores. Led by a man of the Enlightenment, Governor Arthur Phillip (17381814), 300 marines (including their families), 750 convicts, fifteen officials and over 100 sundry livestock disembarked in the last week of January, making camp on the picturesque wooded foreshore of what today is called Circular Quay. It might seem a small intervention in this large, sparsely populated continent but it precipitated a cultural and biological revolution as violent as any that ushered in the modern era.

Today, at this site of first invasion, the harbour ferries unload thousands of commuters into the concrete jungle of Sydneys central business district. Many of these commuters would be familiar with an Indigenous busker, his body painted Aboriginal style, playing amplified modern didgeridoo music with CDS to sell. A permanent fixture on the quay, he reminds us of the special history of this place: that all this concrete, steel and glass has not erased Indigenous culture, and importantly for this book, that transcultural transactions exceed and thereby challenge the boundaries of existing identities and discourses. In the Museum of Contemporary Art, a hundred metres alongfrom the busker, can be seen a different sort of Indigenous art hanging alongside more familiar artworld exemplars of contemporary art.

Throughout most of the nineteenth century the term Indigenous art simply meant art made by Aborigines. Most of it was collected within the colonized territories from those who had survived the invasion, just as tourists now purchase a CD from the busking musician at Circular Quay. This changed around the turn of the twentieth century when a distinction began to be drawn between Aborigines who lived beyond the frontier and those contaminated by modernity. The hunt was on for the last surviving authentic Aborigines before they too inevitably fell, like the busker, to the advance of modernity and its inauthenticities. From this point Indigenous art tended to mean art made by Aborigines living in remote regions. To this day Indigenous art is bifurcated into remote and urban practices, as if it has two histories. Nevertheless, these two histories can be told within a single narrative of transculturation, though one that occurs at different tempos depending on the intensity of the colonial encounter.

In remote Australia Aborigines live in small communities, often comprising a few hundred people who have poor living conditions but usually speak their own language and are close to their traditions. This has allowed them to retain the brand of authentic Indigenous art despite these regions now being well and truly modernized. The brand has been lucrative: between 1996 and the global financial crisis in 2008 it propelled an exponential growth in art sales in both the primary and secondary markets (the latter was worth over A$ 25 million in 2007). Most readers will pick up this book to learn about this phenomenon. I hope to not disappoint them, but I also intend to take them on a larger journey that puts the art into a wider historical context.

One of the most remarkable features of Indigenous Australian art is its extraordinary impact given the small size of the population. The 2011 census counted 669,900 Aborigines, 3 per cent of the Australian population or half the size of Australias fifth largest city, Adelaide. About 80 per cent of Aborigines live in metropolitan and regional Australia, with 34.8 per cent or 233,000 resident in Australias major cities. Only 91,600 Aborigines, or 13.7 per cent, live in remote Australia.