When Henri Vaillancourt goes off to the Maine woods, he does not make extensive plans. Plans annoy him. He just gets out his pack baskets, tosses in some food and gear, takes a canoe, and goes. He makes (in advance) his own beef jerkyslow-baking for many hours the leanest beef he can find. He takes some oatmeal, some honey, some peanut butter. Not being sure how long he will be gone, he makes only a guess at how much food he may need, although he is going into the Penobscot-Allagash wilderness, north of Moosehead Lake. He takes no utensils. He prefers to carve them. He makes his own tumplines, his own carry boards. He makes his own paddles. They have slender blades, no more than five inches across. He roughs them out with his axe and carves them with his crooked knife, a tool well known in the north woods, almost unknown everywhere else. Andhis primary functionhe makes his own canoes. He carves their thwarts from hardwood and their ribs from cedar. He sews them and lashes them with the split roots of white pine. There are no nails, screws, or rivets keeping his canoes togetherjust the rootlashings, in groups spaced handsomely along the gunwales, holding the framework to the bark.

Vaillancourt built his first canoe in 1965, when he was fifteen. He had tried to make other canoes in earlier years, always working by trial and error, until error prevailed. He had never paddled a canoe, had not so much as had a ride in one. In a passionate way, he had become interested in Indian life, and the aspect of it that most attracted him was the means by which the Indians had moved so easily on lakes and streams through otherwise detentive forests. He wanted to feelif only approximatelywhat that had been like. His desire to do so became a preoccupation. He has said that he would have settled gladly for a ride in a wood-and-canvas canoe, or even an aluminum or a Fiberglas canoeany canoe at all. But no one he knew had one. His townGreenville, in southern New Hampshirewas small and had suffered from closing mills and regional depression. Greenville had ponds but no canoes. So far as he could see, there was only one way to achieve his wish. If he wanted to ride in a canoe, he would have to make one, and from materials at hand. White birches were all through the woods around the town. After his first couple of failures, a cousin who had become aware of his compulsion sent him an old copy of Sports Afield in which an article described, without much detail, how the Indians had done it. Henri laid out a building bed, went out and cut bark and saplings, and began to grope his way into a technology that had evolved in the forest under anonymous hands andas he would learnwas much too complex merely to be called ingenious. His standards werewhere else?in their nascent stages, and he made his ribs out of unsplit saplings. What came up off the bed, though, was a finished, symmetrical, classical canoe. He picked it up and took it to a pond. He is lyrical (uncharacteristically lyrical) in describing that moment in that day and the feel of the canoes momentum and response.The first canoe I ever got into was one of my own. I can launch the best ones now and they dont thrill me one-tenth as much. It was the glide, the feel of it, just the sound as it rustled over the lily pads.

He took the canoe home and, before long, destroyed it with an axe. It was a piece of junk, he explains. I didnt want it around to embarrass me. Pieces of it still crop up here, now and then, and they go into the stove. He had had his initial thrill, and it had felt good, but his standards had gone shooting skyward, and that first canoe would never do. He formed an ambition, which he still has, to make a perfect bark canoe, and he says he will not rest until he has done so. He says that some of his canoes may look perfect to other people but they dont to him, because he sees things other people cannot discern. He has built thirty-three birch-bark canoes. He is in his mid-twenties now, andwith the snowshoes and paddles he makes in winterhe does nothing else for a living. Three or four Indians in Canada are also professional makers of bark canoes, and one old white man in Minnesota. All the restthe centuries of themare dead. With a singleness of purpose that defeats distraction, Henri Vaillancourt has appointed himself the keeper of this art. He has visited almost all the other living bark-canoe makers, and he has learned certain things from the Indians. He has returned home believing, though that he is the most skillful of them all.

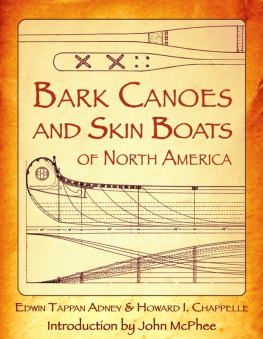

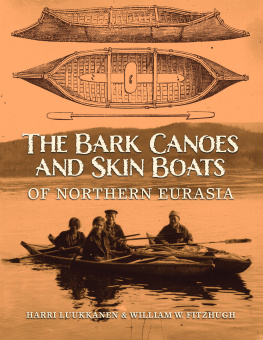

What he learned from the Indians was minor detail, such as using square pegs instead of round ones to secure his gunwale caps. His actual teacher (through the printed sketch and the printed word) was Edwin Tappan Adney, who died in the year that Vaillancourt was born. Without Adney, Vaillancourt might today be working in a plastics factory. Adney was an American who went to New Brunswick in the eighteen-eighties and built a bark canoe under the guidance of a Malecite. He was twenty, and he recorded everything the Malecitetaught him. For the next six decades, he continued to collect data on the making and use of bark canoes. He compiled boxes and boxes of notes and sketches, and he made models of more than a hundred canoes, illustrating differing tribal styles, differences within tribes, and differences of design purpose. A short, low-ended canoe was the kindest to portage, and the best to paddle among the overhanging branches of a small stream. A canoe with a curving, rocker bottom could turn with quick response in white water. A canoe with a narrow bow and stern and a somewhat V-sided straight bottom could hold its course across a strong lake wind. A canoe with a narrow beam moved faster than any other and was therefore the choice for war. Adney so thoroughly dedicated himself to the preservation of knowledge of the bark canoe that he was still doing research, still getting ready to write the definitive book on the subject, when, having reached the age of eighty-one, he died. Over the next dozen years or so, Howard I. Chapelle, curator of transportation at the Smithsonian Institution, went through Adneys hills of paper and ultimately wrote the book, calling it The Bark Canoes and Skin Boats of North America. Large in format, it has two hundred and forty-two pages containing drawings, diagrams, photographs, and a text that frequently solidifies with technical density:

When the bark has been turned up and clamped, the gores may be trimmed to allow it to be sewn with edge-to-edge seams at each slash. This is usually done after the sides are faired, by moving the battens up and down as the cuts are made, then replacing them in their original position. The gores or slashes, if overlapped, are not usually sewn at this stage of construction.

The U.S. Government Printing Office released the book in 1964, and Henri Vaillancourt first heard of it a couple of yearslater, when someone passing through town happened to mention it. He sent for a copy. The book enabled him, while still in his teens, to take a big step toward the perfection he was imagining when he hacked his first boat to pieces. His second completion was, in his words, a very tolerable canoe.