Introduction: The Blackbird,

the Badger and the King

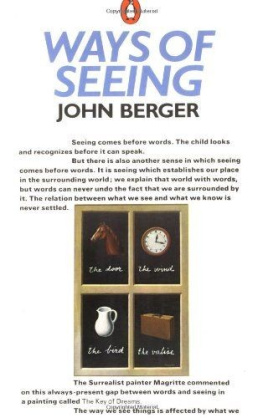

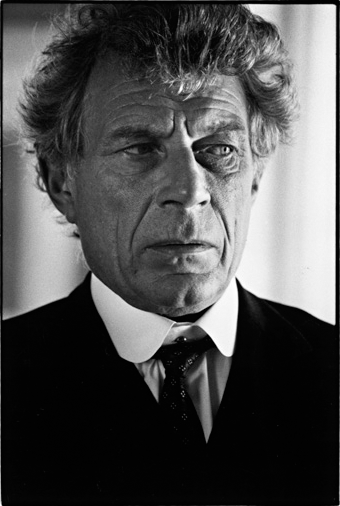

Dressed in full-length leathers, riding his giant Honda Blackbird 1100 CC motorbike, John Berger cuts a curious figure for one of Europes greatest living intellectuals. Residents of Quincy, the sleepy Savoyard village hes called home since 1975, are used to seeing this expat octogenarian (born Hackney, north London, 1926), this costaud white-haired novelist-playwright, film scriptwriter-poet, art critic-essayist, organic intellectual engag, dart through windy Alpine passes at breakneck speeds, looking like a cross between a portly Batman and a real-life Jean Ferrero, Bergers alter ego from To the Wedding.

When Berger first moved to his Haute-Savoie beat, home was several modest rooms near Mieussys Baroque church, with its striking bulbous spire. Summers then were passed on the alpage at Roche-Pallud, high up around 1,500 metres, in a chalet that had neither electricity nor running water. Descending into the valle du Giffre, Berger later settled at a more clement 700 metres in a spacious old farmhouse, replete with barn and ornate spruce balcony, that had been empty for twenty years before his occupation. The property was constructed long before skiers and tourists and kitsch wooden holiday cabins colonized the area. Once upon a time, in a traditional abode like this, denizens ate and slept next to their beasts.

Berger had come to the Haute-Savoie from Geneva, some 50 kilometres due west, where he had lived since 1962, aftercold-shouldering what he said was a closeted, provincial London in those days. So he uprooted himself, initially to an apartment next door to Geneva airport, at avenue de Mategnin, seemingly ready for a fast getaway, only to extricate himself again a decade or so later, dramatically in spite of the short distance, bedding himself down in the hay and in the land of semi-literate mountain peasants.

In coming to alpine France what had Berger forsaken? Phoniness, comfy literary cliques, the limelight, seductive city lights? Perhaps. What had he sought? Authenticity, the need to see and feel oppression close up, in its concrete form? Probably. What had he become? An immigrant? No, he had come here by choice, as a free man, as a privileged man not as a seventh man. Besides, Bergers migration was against the migratory flow of the impoverished masses, those who move exclusively from the countryside to the city and not the other the other way around, not in a direction that corroborates privilege. That is presumably why he prefers to call himself a stranger, somehow always a stranger, even after 35 years of belonging, a stranger in a disappearing culture.

Perhaps Berger was trying to avoid what Guy Debord called the society of the spectacle, the topsy-turvy world in which falsity becomes an ultimate truth we are now compelled to respect, even worship. Debord quit Paris not long after Berger had quit London; the former had gone to the most lost of lost Auvergne villages, to a cottage, he said, that opened directly onto the Milky Way. But Debord had come to cut himself off, to turn his back on society, playing no part in local auvergnate life. He lived behind a high stone wall, a wall a mason had built even higher at Debords behest. Bergers house, by contrast, has no walls and is completely open to the street. Berger hates walls, walls of separation, walls that cut people off from one another, walls that keep people in as well as out. Anybody can come and knock at Bergers front door; his is one of the first houses on the left as you enter Quincy, just as the lane bends and narrows.

) Rather than turning his back on locals, Berger has embraced them, has integrated himself within village life with his American wife, Beverly, even raising a kid there Yves, an artist, born in 1976, who attended the local school and now lives next door; he uses papas barn as his studio. (Berger also has a daughter, Katya, a translator and film critic, and Jacob, a filmmaker, both from an earlier, formative relationship with the Russian-born linguist Anya (Anna) Bostock, with whom Berger penned several essays and translated the poetic works of Aim Csaire and Bertolt Brecht. G., Bergers Booker Prize-winning novel, is dedicated to Anya, and to her sisters in Womens Liberation.)

Berger claims he came to the Haute-Savoie to learn, to understand an endangered species, to see and feel oppression first-hand, mimicking with the French peasantry what Karl Marxs old comrade Frederick Engels did with Manchesters working class, understanding their condition, their worsening condition. Berger wanted to see where Europes migrant workers set off from, wanted to witness the old life they had left behind. I came to listen, he says, in order to write, not to speak on their behalf. I wanted to touch something that had a relevance way beyond the French Alps. Far from retreating, I was homing in on a point that touched a nerve bud about a very important development in contemporary world history.