The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

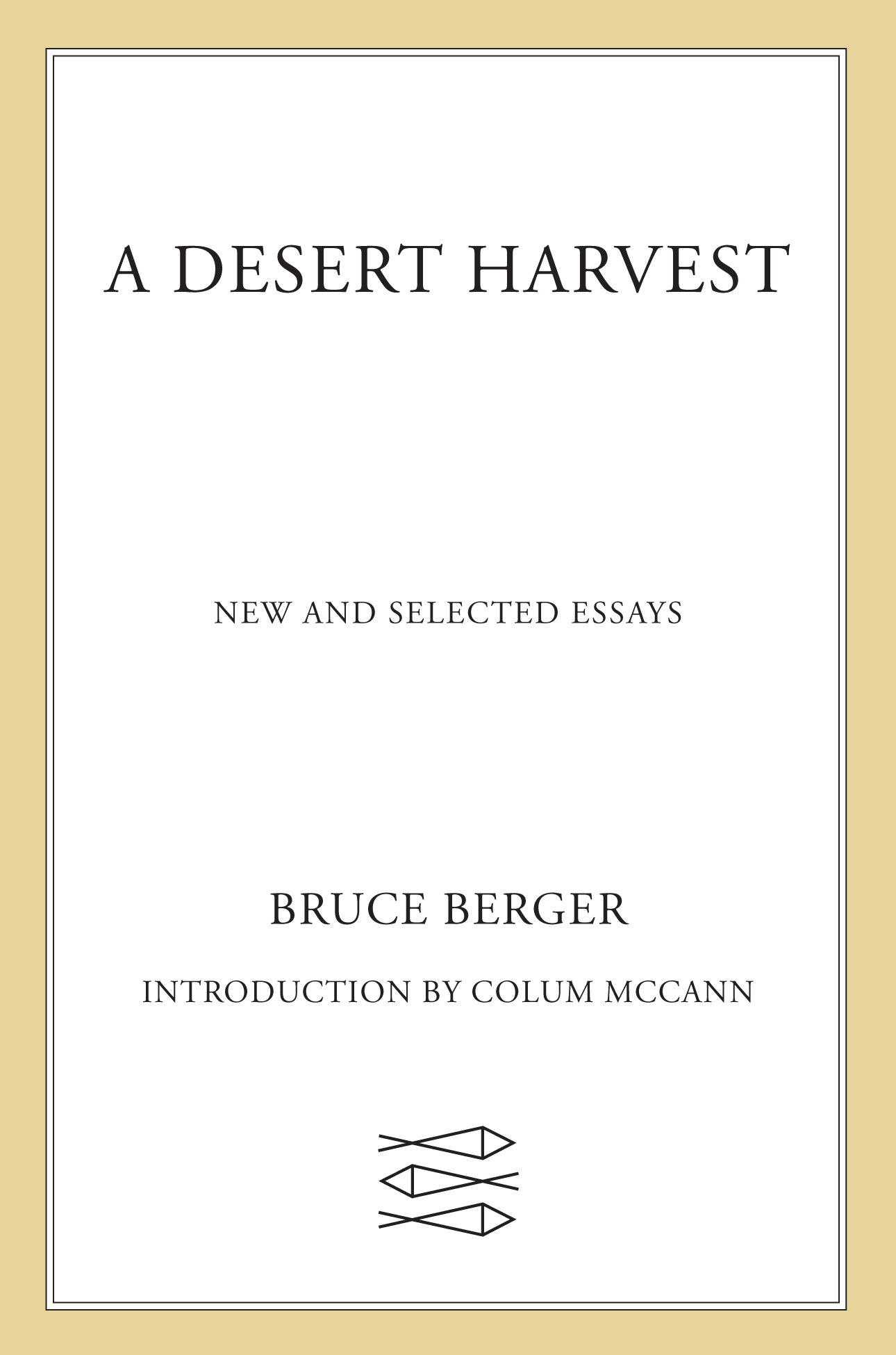

Colum McCann

The American musician John Cage is credited with helping to pioneer the idea of the prepared piano, where unusual itemsamong them tuning forks, screws, spoons, rubber tubes, cardboard, plastic sheathing, bolts or paper clipscan be inserted on or between the strings to alter the nature of the pianos sound. The music, then, is changed. A note can be elongated or damped or even turned inside out.

The degree of change is dependent, of course, upon what is used to alter the piano, but these days just about anything can find its way into the belly of the electric upright or the baby grand. All one needs to shift the musical landscape is the hardware and a touch of imaginative genius. The first is easy enough to come by; the second is obviously a lot more elusive.

It should come as no surprise that apart from his work as an essayist and a poet, Bruce Berger is also a pianist of the highest order. What I mean is that he actually plays the pianoat parties, at fund-raisers, in homes, in concert halls. He knows his music and he can command an audience. He might once have made a living as a musician, but thankfully he did notinstead, for quite a while now, Bruce Berger has been sliding a series of prepared pianos out into the literary landscape.

Berger appears to be a classicist at firstthe sort of writer who might guide you into the drawing room and play quite competently, even beautifully, that which might be expected: the taut essay that opens up the possibilities that lie just beyond the windows. But spend a little more time listening and you begin to understand that he has indeed shifted the timbre of the piano and that the windows are, in fact, not only open but daringly so, floor to ceiling, north to south, east to west. He has prepared the language somehow, secretly, imaginatively, and it contains a sort of whisper to break the convention of the drawing room, to entice you outside to experience the wind and the light and the dust. The adventure starts here. How about wheeling the piano down the hill? How about swerving in and out of a line of neglected cactus? How about leaving it for a moment in that dormant arroyo? How about turning a corner in the town of La Paz into another street, into an alleyway just beneath the convent? How about sounding out a few notes of old Chicago jazz to surprise the living daylights out of your desert? How about turning the piano away from the sunset? How about throwing out a little discordant noise from the stars?

Which is to say that Bruce Berger is a literary surprise: he has prepared the piano and we might not ever know how he did it, but somehow he makes the local sound universal, and at the same time brings the universal back around to the local.

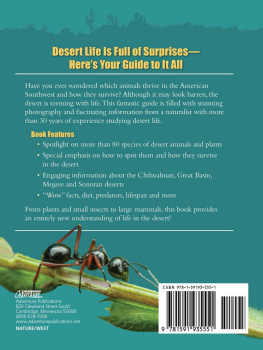

Bruce Berger has always been on the inside of the curve. As he says himself, he sank his first earthly roots not in the Chicago of his childhood, but when he set foot in the Sonoran Desert. After that, he floated in Glen Canyon before it was dammed; drove down the Baja Peninsula before it was paved; lived on Cannery Row before it became a boutique; and put down roots in Aspen before it appeared in the national gossip rags. He never clangs down too hard on these key moments in his life. Hes not interested in drawing attention to himself; rather, its what happens around him that truly matters, the otherness of life. Theres no showing off or fanning out the coattails. He exists quietly in these places and times, and manages, then, to draw out their exact essence.

In fact, Berger owns a beautiful wood cabin right in the heart of Aspen, Colorado. Whats fascinating about this is that theres little or nothing of contemporary Aspen to it at all: its modest, its shy, its quiet, its functional, its humble, it hasnt come under the knife. It sits on a tiny flick of a path just off Main Street, surrounded by rental units yet somehow all on its own, with an incredible western view, a perfect reflection of so much of his work: right there, in the heart of things, yet isolated and thrown back too. (With a piano, of course, amid shelves and shelves full of neatly stacked books: I was lucky enough, once, to spend a couple of weeks there while writing a novelI swear I can still hear the books whispering to the piano.)

A taste for the desert is a taste for ultimates, Berger writes, and death is the backdrop against which all we know comes to brilliance. There is often a whiff of sadness in Bergers work: the landscape under threat, the creativity stifled, the familiar house lost, the highway arriving or never even beginning, the mother figure passing away, the rare bird flitting from the branch.

At the same time he manages a sense of astonished being. Just because its dark doesnt mean that the darkness prevails. Bergers world is not mannered or prescribed in any way. He discovers the gorgeous in the individual. He sees finality as a radiance. Upon coming upon a dying plant, he finds that the more grotesque its deformities, the more humanly it seems to express itself.

All the essays gathered hereshort and longspeak to Bergers glocal world, global and local both. He speaks to physics and environmentalism and a new form of mythology in the ordinary. The short essays read like pure poems. The longer ones allow themselves to dawdle awhile. Theres a bravery in this. Picking a favorite is like picking a child, of course. I adore the mad genius of Cactus Pete, for instance, and I am charmed by the pithy beauty of How to Look at a Desert Sunset, but the essay that continues to rattle in me is The Search for Mata Hari: read it and weep, and then exalt in layer upon layer of discovered music. Walk through the streets of La Paz in a new pair of shoes bought simply because one man can play the piano and many men and women want to listen. (I hope its not too much of a spoiler, but Id like to echo the last line, which reads: That was extraordinary. I hope I can hear it again.)

Bergers writing is meticulous and beautiful, discerning and tender. It throws off the appearance of ease, but one can tell that an ocean of thought and craft has gone into each and every sentence. There is a lot of work underneath the words. His prose has sometimes been described as having a whiff of the intellectual, which in America seems to be a curse. It is indeed smart and clever, but he manages to avoid writing in rapt self-abstraction. It is as if Wallace Stevens has told him that the worst of all things is not to live in a physical world. Berger himself has often talked about writing toward the intersection of humanity and landscape.

His other concern is with language and its possibilities, its areas of recalcitrance and exhaustion, its capacity to aestheticize and therefore in some sense redeem quotidian reality. Whether were canyons or musicians, he writes, we must dig into it and shape what we can. Indeed, the side canyons lead us to the deeper areas of experience. A large part of the charm comes in the buried humorwhen it becomes apparent, its like discovering ice in the middle of the hike, rare and refreshing. Sometimes Berger, especially in his self-effacing slanthonestycan make you flat-out belly-laugh. You can almost see the little Chicago boy in shorts and mismatched shirt standing on the edge of the suburbs in Phoenix, ready to dash out and get marvelously lost.