OTHER THOMAS MERTON BOOKS PUBLISHED BY NEW DIRECTIONS The Asian JournalBread in the WildernessCollected PoemsGandhi on Non-ViolenceThe Geography of LograireLiterary EssaysMy Argument with the GestapoNew Seeds of ContemplationRaids on the UnspeakableSelected PoemsThomas Merton in AlaskaThoughts on the EastThe Way of Chuang TzuThe Wisdom of the DesertZen and the Birds of Appetite Copyright 1944, 1949 by Our Lady of Gethsemani Monastery Copyright 1946, 1947 by New Directions Copyright 1952, 1954, 1955, 1956, 1957, 1961, 1962, 1963, 1967. 1968 by The Abbey of Getharmani, Inc. Copyright 1964 by The Abbey of Getharmani Copyright 1968 by Thomas Merton Copyright 1961, 1963, 1965. 1966, 1967, 1968, 1969, 1970, 1971, 1976, 1977,

Copyright 1944, 1949 by Our Lady of Gethsemani Monastery Copyright 1946, 1947 by New Directions Copyright 1952, 1954, 1955, 1956, 1957, 1961, 1962, 1963, 1967. 1968 by The Abbey of Getharmani, Inc. Copyright 1964 by The Abbey of Getharmani Copyright 1968 by Thomas Merton Copyright 1961, 1963, 1965. 1966, 1967, 1968, 1969, 1970, 1971, 1976, 1977,

1985, 2005 by The Trustees of the Merton Legacy Trust Copyright 2005 by Lynn R. Szabo Copyright 2005 by Kathleen Norris Copyright 2005 by Paul Quenon The poem Ermine Street, on p. 46 are used by permission of the Trustees of the Merton Legacy Trust. 46 are used by permission of the Trustees of the Merton Legacy Trust.

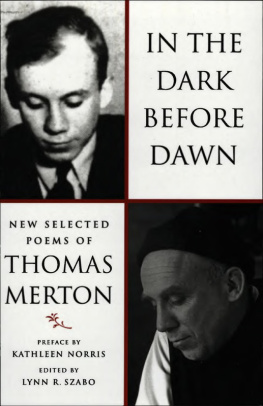

All rights reserved. Except for brief passages quoted in a newspaper, magazine, radio, or television review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher. Book design by Sylvia Frezzolini Severance First published as New Directions Paperbook 1005 in 2005 Published simultaneously in Canada by Penguin Books Canada Limited Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Merton, Thomas, 19151968 In the dark before dawn new selected poems of Thomas Merton / edited with an introduction and notes by Lynn R. Szabo: preface by Kathleen Norris. p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0811223102 (e-book) I. Szabo, Lynn. II. Title. PS3525.E7174A6 2005 811.54dc22 2004030957 New Directions Book are published for James Laughlin by New Directions Publishing Corporation, 80 Eighth Avenue, New York, NY 10011 I think poetry mustI think poetry mustStay open all nightIn beautiful cellarsCanto 53 from Cables to the Ace (1968)

PREFACE

T he prolific writer Thomas Merton had much to say to the world, but his poems are the fruit of listening.

Merton recognized early on that in an increasingly violent and cacophonous world, the ability to listen is constrained, and even threatened. Particularly in his verse, he became a prophet of language. In Cables to the Ace, Merton speaks of Words replaced by moods. Actions punctuated by the hard fall of imperatives. More and more smoke No one need attend. Listening is obsolete.

So is silence. (150) Writing in the late 1960s, Merton foresaw the relentless onslaught of commercial and political verbiage that so distracts and wearies us in the early twenty-first century. Listen is the first word of St. Benedicts Rule for monks, and in order to hear well, one must be quiet. If today both silence and listening are difficult to find, increasingly relegated to the realm of the monastery, it is also true that those monasteries are much in demand. The guest quarters at Mertons abbey of Gethsemani, like those of many Benedictine and Trappist monasteries in America, are often booked a year in advance.

It would appear that monks, the inheritors of a 1,700-year-old Christian tradition, and the silence they foster, are not anachronistic, but more necessary than ever. All poets must learn to listen, in the words of Benedict, with the ear of the heart. (RB Prologue; 1) They must learn to nurture a certain quality of attention that lends itself to the writing of verse. The poet who is a monk lives in a way that intensifies this process, as a life pared down to its essentials encourages close attention to the resonant tones of scripture and the lighter notes of wind and birdsong. Monks spend a good part of their time listening to one another recite scripture and the poetry of the psalms, and their days remain stubbornly in tune with the rural rhythms of sunrise and sunset. (Mertons Selected Poems, 1967 ed., xv) In this book we hear moonlight ringing upon the ice as sudden as a footstep (53) and the cries of playing children, Clear as water, their words coming from a distance, words that flower / On little voices, light as stems of lilies. (77) We stand with Merton in the cemetery at Gethsemani and hear the treble harps of night begin to play in the deep wood praising the holy sleep of the monks buried there, as all the frogs along the creek / Chant in the moony waters to the Queen of Peace. (33) A vast hospitality is contained in these spare lines, as trees, insects, frogs, the moon, the Blessed Virgin, and the remembered dead are each acknowledged and made welcome. (33) A vast hospitality is contained in these spare lines, as trees, insects, frogs, the moon, the Blessed Virgin, and the remembered dead are each acknowledged and made welcome.

The generous gesture is typical of Merton and echoes an earlier poem, For My Brother: Reported Missing in Action, 1943, in which he summons for his brother Christs tears that fall silently, Like bells upon your alien tomb. / Hear them and come: they call you home. (181) To venture a dangerously worn word, Merton has a mystics sense of unity, and in his poems he wants to bring as much together as he can. Sometimes he does it with monastic simplicity, as in the brief, poignant Song for Nobody, in which a sunflower is seen as a gentle sun in whose dark eye / somebody is awake, and heard as it Sings without a word / By itself. (95) But Merton can also insist on plenitude, and a wild extravagance flowers in much of his work, such as a lengthy meditation of flying out of OHare during the 1960s. He asks, Should the dance of Shivashapes / All over flooded prairies / Make hosts of (soon) Christ-Wheat / Self-bread which could also be / Squares of Buddha-Rice (167) The farmland and rivers he passes over flood him with images of Vietnamese villages in flames, generals giving news conferences, and the literature of his boyhood, the adventures of both Tom Swift and Huckleberry Finn.

Flying west, over South Dakota, he envisions Mount Rushmore as four Walt Whitmans / Who once entrusted the nation to rafts, and hears a politician lying, promising a weapon, presumably napalm, that as a mildly toxic invention can harm none / But the enemy. (170) The thematic organization of this book allows the reader to journey with Merton through the themes that were most important to him: being in many different landscapes and staying in one place, worshiping and contemplating, being a person of faith in a world of doubt and fully engaging with that world. Merton repays the world with constant, close attention, amplified by wit, humor, and a no-nonsense, finely tuned bullshit detector. He writes with both praise and scorn of cities, recognizing that they are full of human beings, and thus opportunities for grace: Here in the jungles of our waterpipes and iron ladders, / Our thoughts are quieter than rivers, / Our loves are simpler than the trees, / Our prayers deeper than the sea. (25) But the city also is fueled by cruel economies that allow an American executive to swim in India, in chlorinated / Indigo water where no / Slate-blue buffalo has ever / Got wet, (21) while ignoring the impoverished children playing in dust hard by the hotels front door. What may be most valuable for the contemporary reader is the way that Mertons poems offer evidence that ecstasy, and specifically religious ecstasy, is still possible in this world, and still meaningful.

Copyright 1944, 1949 by Our Lady of Gethsemani Monastery Copyright 1946, 1947 by New Directions Copyright 1952, 1954, 1955, 1956, 1957, 1961, 1962, 1963, 1967. 1968 by The Abbey of Getharmani, Inc. Copyright 1964 by The Abbey of Getharmani Copyright 1968 by Thomas Merton Copyright 1961, 1963, 1965. 1966, 1967, 1968, 1969, 1970, 1971, 1976, 1977,

Copyright 1944, 1949 by Our Lady of Gethsemani Monastery Copyright 1946, 1947 by New Directions Copyright 1952, 1954, 1955, 1956, 1957, 1961, 1962, 1963, 1967. 1968 by The Abbey of Getharmani, Inc. Copyright 1964 by The Abbey of Getharmani Copyright 1968 by Thomas Merton Copyright 1961, 1963, 1965. 1966, 1967, 1968, 1969, 1970, 1971, 1976, 1977, PREFACE

PREFACE