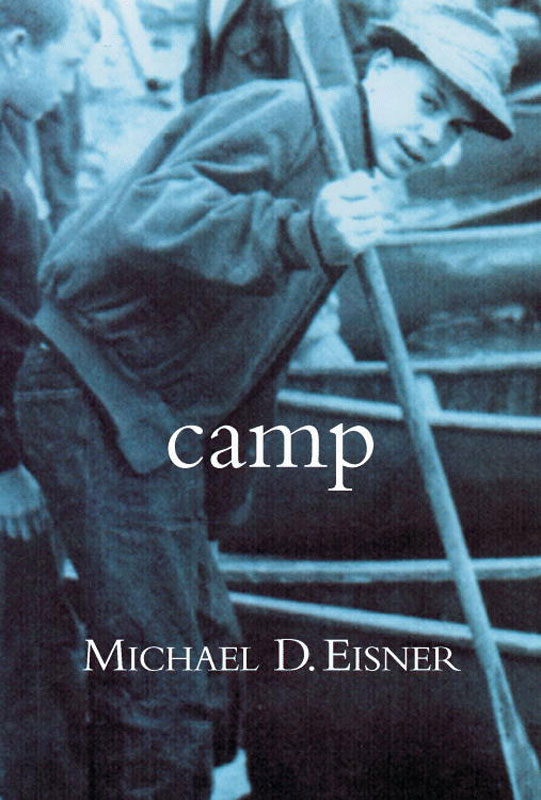

Copyright 2005 by The Eisner Foundation, Inc.

Foreword 2005 by John McPhee

All rights reserved.

Endpaper maps and photograph accompanying the dedication 2005, archives of Camp Keewaydin; photograph accompanying author bio courtesy of the Eisner family.

Song lyrics found in the prologue are from Go the Distance, music by Alan Menken, lyrics by David Zippel, 1997 Wonderland Music Company, Inc. and Walt Disney Company. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

Warner Books

Hachette Book Group USA

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our Web site at www.twbookmark.com.

First eBook Edition: June 2005

ISBN: 978-0-7595-1398-3

To Waboos

Niminwenindam Kikeniminn.

(Algonquin for I am happy to know you.)

If forty years in the entertainment business have taught me one thing, its that any creative project requires the devotion and dedication of many. This small labor of love was no different. Larry Kirshbaum at Warner Books believed in this book long before I had written its first word, and his wisdom, enthusiasm, and good humor... and the fact that he went to Camp Indianola in Madison, Wisconsin... were all appreciated along the way. Also, I want to thank Aaron Cohen for his tireless efforts in helping to bring this book to lifewithout him it would still be just a good idea. I want to acknowledge my three sons, who carried on the family tradition at Keewaydin and kept my love for the place alive. I also want to thank my lawyer of thirty years, Irwin Russell, for riding the currents with me. My office staff, Virginia Hough, Beth Huffman, and Dee Case, helped me track down old scrapbooks, photos, and memorabilia from my daysand my sons daysat camp. Peter Hare and his staff at Keewaydin couldnt have been nicer, more supportive, or more accommodating. And Sandy Chivers and everyone at Keewaydin Temagami were the most gracious of hosts during our visit. But of course I want to especially thank my wife, Jane, who patiently listens to camp stories told often more than once.

John Mcphee

At Vassar College a few decades ago, I read to a gymful of people some passages from books I had written, and then received questions from the audience. The first person said, Of all the educational institutions you went to when you were younger, which one had the greatest influence on the work you do now? The question stopped me for a moment because I had previously thought about the topic only in terms of individual teachers and never in terms of institutions. Across my mind flashed the names of a public-school system K through 12, a New England private school (13), and two universitiesone in the United States, one abroadand in a split second I blurted out, The childrens camp I went to when I was six years old.

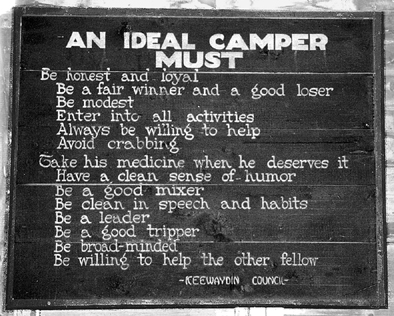

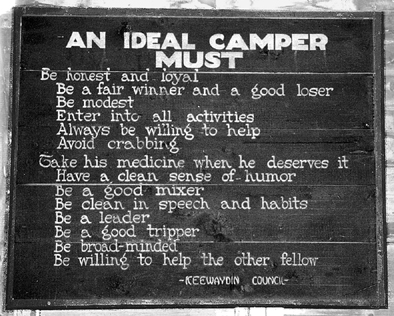

The response drew general laughter, but, funny or not, it was the simple truth. As I once began a piece of writing in The New Yorker magazine, I grew up in a summer campKeewaydinwhose specialty was canoes and canoe travel. It was at the north end of Lake Dunmore, about eight miles from Middlebury, in Vermont. In addition to ribs, planking, quarter-thwarts, and open gunwales, you learned to identify rocks, ferns, and trees. You played tennis. You backpacked in the Green Mountains on the Long Trail. If I were to make a list of all the varied subjects that have come up in my articles and books, adding a check mark beside interests derived from Keewaydin, most of the entries would be checked. I spent all summer every summer at Keewaydin from age six through fifteen, and later was a counselor there, leading canoe trips and teaching swimming, for three years while I was in college.

The Kicker was the name of the camp newspaper, and its editor was my first editor, a counselor named Alfred G. Hare, whose surname translated to the Algonquian Waboos, a nickname that had been with him from childhood and would ultimately stay with him through his many years as Keewaydins director. Waboos was a great editor. He laughed in the right places, cut nothing, and let you read your pieces aloud at campfires. If this book, in its varied appreciations of Keewaydin, has a hero, hes it.

When I first arrived at Keewaydin as a child (my father was the camps physician), the name Eisner was all over the placeon silver trophies and on the year-by-year boards in the dining hall that listed things like Best Swimmer, Best Athlete, Best Singles Canoe. The author of this book was not one of those Eisners. When I first arrived at Keewaydin, he was still pushing zero. He had five years to wait before he was born. His father, Lester, was among the storied Eisners, and so were assorted uncles and cousins. Over time, multiple Eisners would follow. In 1949, when Lester Eisner brought Michael to the camp to see if he would like to enroll there (a scene of some hilarity that you will find a few pages hence), I was in the first of my three years as a counselor in the oldest of the four age groups into which the camp was divided. In the two summers that followed (the last ones for me), he was in the youngest group and I didnt know him from Mickey Mouse. I was aware only that another Eisner had come to Keewaydin.

Summer camps have varying specialties and levels of instruction. They differ considerably in character and mission. No one description, positive or negative, can come near fitting all of them or even very many. Keewaydin was not a great experience for just anybody. My beloved publisherRoger W. Straus, Jr., founder of Farrar, Straus & Girouxwent to Keewaydin when he was thirteen years old and hated every minute of it. That amounts to about eighty thousand minutes. Over the years, he spent at least a hundred thousand minutes making fun of me for loving Keewaydin. The probable cause was Keewaydins educational rigor. Gently but firmly, you were led into a range of activity that left you at the end of the summer with enhanced physical skills and knowledge of the natural world. You wanted to go back, and back. Mike Eisner went back in 2000 (hardly for the first or last time). He was fifty-eight. Keewaydin was celebrating the career of its eighty-five-year-old emeritus director. Three people spoke at a Saturday night campfire. Each was introduced only by name, with no mention of any business or profession or affiliation, just, in turn, Peter Hare, Russ MacDonald, Mike Eisner. In his blue jeans and ball cap, walking around the flames with his arms waving, Eisner told three hundred pre-teen and early-teen-aged kids escalating stories of his own days at Keewaydin. They listened closely and laughed often. Few, if any, knew who else he was.

It All Started At A Knicks Game

New York, Madison Square Garden, courtside, 2001. The Knicks against the Pacers. The score was tied, and halftime was about to end.

I could sense that I was about to be approached by a stranger. His intent, I assumed, was to offer a comment about a new ride at Disney World or hand me a movie script.

Instead, he gave me a card identifying himself as George Stein, head of the Tri-State Camping Conference. Above the noise of an impatient crowd as the second half began, he said hed heard I was an enthusiast of summer camp. His group was holding an annual conference and wanted me to speak about my experiences. Without hesitation, I said, yes. The word