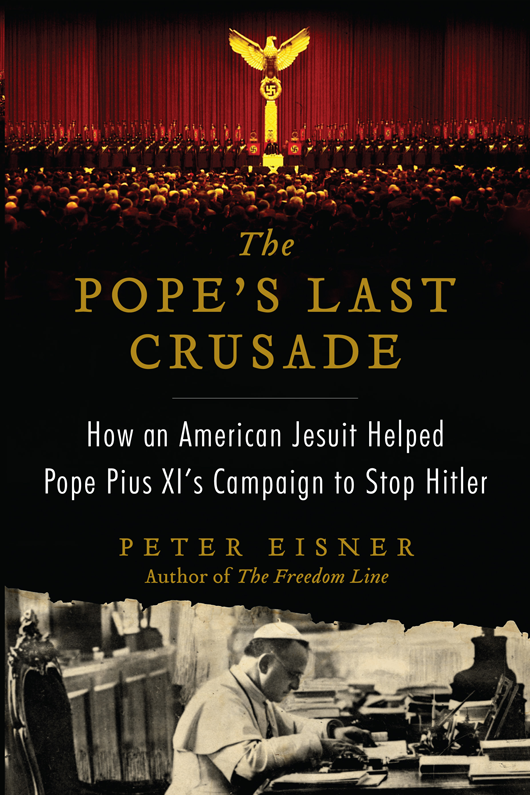

NONFICTION

The Freedom Line: The Brave Men and Women Who Rescued

Allied Airmen from the Nazis During World War II

COAUTHOR OF

The Italian Letter: How the Bush Administration Used a Fake

Letter to Build the Case for War in Iraq

Author photograph by Miguel Pagliere

PETER EISNER has been an editor and reporter at the Washington Post, Newsday, and the Associated Press. His 2004 book, The Freedom Line, was the recipient of the Christopher Award. Eisner also won the InterAmerican Press Association Award in 1991, and was nominated for an Emmy in 2010 for his role as producer at the PBS news program World Focus. Eisners other books include The Italian Letter, written with Knut Royce, which traces fraudulent U.S. intelligence prior to the U.S. invasion of Iraq. He lives in Bethesda, Maryland.

Visit www.petereisner.com

Visit www.AuthorTracker.com for exclusive information on your favorite HarperCollins authors.

To my parents

It is on the whole more convenient to keep history and theology apart.

H. G. Wells, A Short History of the World

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

A Settling of Accounts

ONE

Nostalgia Confronts Reality

TWO

A Crooked Cross

THREE

The Imposition of the Reich

FOUR

The Popes Battle Plan

FIVE

The Flying Cardinal

SIX

A Democratic Response

SEVEN

In the Heat of the Summer

EIGHT

The Popes Discontent

NINE

Shame and Despair

TEN

A New Year and an End to Appeasement

ELEVEN

Will There Be Time?

TWELVE

Change Overnight

THIRTEEN

The New Regime

New York City, May 20, 1963

T HE REVEREND JOHN LaFarge was fully aware of his place and moment in life. He had dedicated himself to kindness and goodness, to peace and principles. Now in his final years, at age eighty-three, he recognized that his life was coming full circle.

If by chance death comes suddenly and unannouncedand who can be sure that it wont, he had said, it will come as a friend. Our own terminal Amen will ring true as the response to the Creators primal Amen which sent us into this world.

He had accomplished a great deal, though there was still a lot left to do. High among the priorities these days was his support for Martin Luther Kings upcoming march on Washington. LaFarge had spoken out strongly and frequently about civil rights as fundamental to the promise of America. He was frequently in touch with King and others planning the march, especially his longtime friend, Roy Wilkins, the executive director of the NAACP. For half a century, LaFarge had been one of the Catholic Churchs clearest voices calling for racial justice.

LaFarge had been a young Jesuit priest working, praying, and living with poor blacks in rural Maryland and defended their chance to obtain equal education and equal rights. He marveled at their resilience; they were downtrodden yet they still possessed that great flame of faith... for three centuries had glorified the lives of Marylands black folk.

He knew, however, that without adequate schools, the Faith would perish, and the folk themselves would be defrauded of their legitimate development. LaFarge had long wanted the Catholic Church to be a leader in fighting discrimination. Before World War II, LaFarge was a lonely voice among white clergy when he called for an immediate end to racism. In 1936, he had written an influential book, Interracial Justice, which called on churches to lead the fight against racism. Once the light of science is turned upon the theory of race, he wrote, it falls to pieces and is seen to be nothing but a myth. The obliteration of racial injustice and intolerance would continue to be his lifes work.

He still felt the fire of justice and saw reasons for optimism. Dr. King had been leading a protest movement in Birmingham, Alabama, where eleven hundred African American students had been arrested for civil disobedience against segregationbravely seeking the simple right to sit at a luncheon counter, to drink from a water fountain, or to read a book in a library. The civil rights movement was maturing. Great leaders had emerged; white men and black men walked together, demanding justice. The end of legalized racism was in sight.

The younger Jesuits around LaFarge adored him and noticed with dismay that Uncle John was ailing, haggard at times and hiding his discomfort as he ambled about the Jesuit community residence at America magazine on West 108th Street. Sometimes he appeared to be in so much pain that he could hardly take a step at all.

Not that LaFarge had pulled back on his schedule. He never complained about physical ailments and always maintained his good humor. He had lived and worked with his Jesuit brethren at the America magazine headquarters since 1926, rising from associate to the editor of the magazine, and now writing a frequent column. Even today, he came and went, prayed, shared meals, and discussed current events with the others around him.

And yet Uncle John was a distant, mysterious figure. He seemed to carry secrets with him. Perhaps, in these final days, LaFarges determined silence was wavering, and he was ready to unburden himself. Every evening after supper, the Jesuits gathered in the downstairs recreation room, where they chatted and sipped after-dinner drinks. One night, LaFarge began talking about something he had never mentioned. He began by asking if he had ever told them the story of his trip to Europe, the summer before World War II. He knew he hadnt and all other conversation stopped.

Exactly twenty-five years earlier, in May 1938, LaFarge had been sent to Europe on a reporting assignment; his goal was to study the churchs welfare under siege, while at the same time taking the pulse of the continent. LaFarge described his trip, in part, as a fact-finding mission. He had heard very clearly what was being said about Europe and Hitler and the threat of war, but he wanted evidence, wanted to understand and to describe life under Hitler and the prospects of war. It was his first trip to Europe in decades and his first as a foreign correspondent. There was an aspect of nostalgia to the triprecalling the time as a young man when he had set out on his first life adventure at the turn of the century, steeped in old-world literature, devoted to his faith.

But everything was different in Europeand he wasnt sure what he would find. He did not trust the reports in the New York newspapers and the dispatches from news agencies. Was Europe on the brink of an inferno? Would a new world war engulf Europe? Or was it all an exaggeration? He wanted to listen, to ask questions of people he could trust, of common folk, and of politicians. Being a correspondent had given him a privileged status to meet with opinion makers, other journalists, key politicians, and friends in the clergy. LaFarge was able to observe the final throes of freedom.

By the spring of 1938, Hitlers Greater Germany extended into Austria; the priest had expected to be followed, monitored, and spied upon.

Next page