DARK HISTORY OF THE

POPES

BRENDA RALPH LEWIS

This digital edition first published in 2012

Published by

Amber Books Ltd

Bradleys Close

7477 White Lion Street

London N1 9PF

United Kingdom

Website: www.amberbooks.co.uk

Appstore: itunes.com/apps/amberbooksltd

Facebook: www.facebook.com/amberbooks

Twitter: @amberbooks

Copyright 2012 Amber Books Ltd

ISBN: 978 1 908696 32 8

PICTURE CREDITS

AKG Images; Alamy; Art Archive; Art-Tech/John Batchelor; Bridgeman Art Library;

Cody Images; Corbis; De Agostini Picture Library; Getty Images; Heritage Image

Partnership; iStockphoto; Library of Congress; Mary Evans Picture Library;

Photos12.com; Photos.com; Public Domain; Ronald Grant Archive;

Science Photo Library; TopFoto

All rights reserved. With the exception of quoting brief passages for the purpose of review no part of this publication may be reproduced without prior written permission from the publisher. The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. All recommendations are made without any guarantee on the part of the author or publisher, who also disclaim any liability incurred in connection with the use of this data or specific details.

www.amberbooks.co.uk

CONTENTS

The Basilica of St. Peter in the Vatican City (pictured), constructed between 1506 and 1626, is one of the holiest sites in Christendom.

INTRODUCTION

The Pope in Rome holds the oldest elected office in the world. In the nearly 2,000 years it has existed, the papacy has helped forge the history of Europe, and has also reflected both the best and the worst of that history. Several popes schemed, murdered, bribed, thieved and fornicated, while others committed atrocities so appalling that even their own contemporaries were shocked.

T his was especially true of the darkest days of the papacys dark history when Christendom was gripped by a hysterical fear of witchcraft or any dissent from the path of true religion as ordained by the popes and the Catholic church. Some of the most heinous crimes ever committed in the name of religion all of them with papal sanction occurred during the five centuries or so during which a ferocious struggle raged over Europe to eliminate error: any belief, practice or opinion that deviated from the official papal line.

Virtual genocide, for example, eliminated the Cathars, an ascetic sect centred around the southwest of France, who believed that God and the Devil shared the world. In 1231, the first Inquisition was introduced to deal with them. Inquisitors used horrific tortures such as the rack and the thumbscrew to extract confessions. The end was often death in the all-consuming flames of the stake. As well as heretics, thousands of supposed witches, wizards, sorcerers and other agents of the Devil died in the same horrific way.

In less savage form, the Inquisition caught up with the 17th-century astronomer Galileo Galilei, who was censured for supporting views about the structure of the Universe that were contrary to Church teachings. Galileo believed in that the Earth orbited the Sun, while the Church taught that the Earth was at the centre of the universe. Galileo ended his life as a prisoner in his own house, and some 350 years passed before the Vatican admitted that he had been right all along.

The Vatican had its own, self-imposed prisoners: the five popes who declined to recognise the Kingdom of Italy and for nearly sixty years refused to leave the precincts of the Vatican. Eventually, in 1929, Pius XI realised that isolation was making the papacy an anachronism and signed the Lateran Treaties that enabled it to rejoin the modern world.

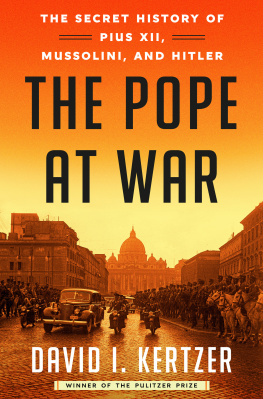

Ten years later, in 1939, the extreme dangers of this modern world were brought home to another Pius Pope Pius XII who was confronted with the combatants in World War II, both of whom sought papal sanction for their efforts. Pius XII gave his support to neither, but by following his own path made himself a hero and a saviour to some, but a villain, even a criminal, to others.

To the east of the basilica is the Piazza di San Pietro, or St. Peters Square, flanked by 284 Doric columns topped by 140 statues of saints (pictured).

St Peters Basilica in Vatican City (pictured) was by tradition the burial site of St Peter, the first Bishop of Rome and first in the line of papal succession. Here its dome rises above the facade begun in 1605 by the architect Carlo Maderna.

I

THE CADAVER SYNOD, THE RULE OF THE HARLOTS, AND OTHER VATICAN SCANDALS

One thousand years ago and more, political instability was rife in Rome. At that time, the image of the papacy was everything from outlandish to weird to downright appalling. All kinds of dark deeds stuck to its name. Corruption, simony, nepotism and lavish lifestyles were only part of it, and not necessarily the worst.

Benedict IX (pictured), one of the most scandalous popes of the 11th century, was described as vile, foul, execrable and a demon from Hell in the disguise of a priest.

D uring the so-called Papal Pornocracy of the early tenth century, popes were being manipulated, exploited and manoeuvred for nefarious ends by mistresses who used them as pawns in their own power games. With some justification, this era was also called the Rule of the Harlots.

HOW TO FIND A MISSING POPE

So many popes were assassinated, mutilated, poisoned or otherwise done away with that when one of them disappeared, never to be seen again, it was only natural to scan a list of violent explanations to find out what had happened to him. Death by strangulation in prison was a frequent cause. Had the vanished pope been hideously mutilated and therefore made unfit to appear in public? Had he made off with the papal cash box? Or should the brothels and other houses of ill repute be searched to find out if he was there? Often, there was no clear answer and explanations were left to gossip and rumour.

A VARIETY OF VIOLENT ENDS

The variety of violent ends suffered by popes during the Papal Pornocracy was astonishing. For example, in 882 CE one pope, John VIII, failed to die sufficiently quickly from the poison administered to him. His assassins, losing patience, smashed his skull with hammers to move things along. A tenth-century pope, Stephen IX, suffered horrific injuries when his eyes, lips, tongue and hands were removed. Amazingly, the unfortunate man survived, but was never able to show his mutilated face in public again. Another pope, Boniface VI, was elected to the Throne of St Peter even though he had twice been downgraded for immorality. Boniface was said to either have died of gout, or was poisoned or deposed and sent away to allow another pope, Stephen VII, to take his place. Boniface disappeared from history but he did so with suspicious rapidity: his reign lasted only 15 days. Afterwards, Stephen was let loose on the many powers and privileges of the papacy that he was expected to use for the benefit of his sponsors, the House of Spoleto in central Italy and its domineering chatelaine, the Duchess Agiltrude, the instigator of the scandalous Cadaver Synod of 897 CE.