Table of Contents

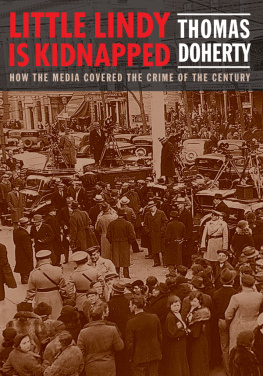

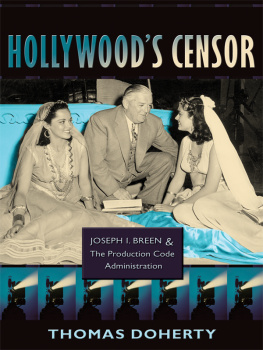

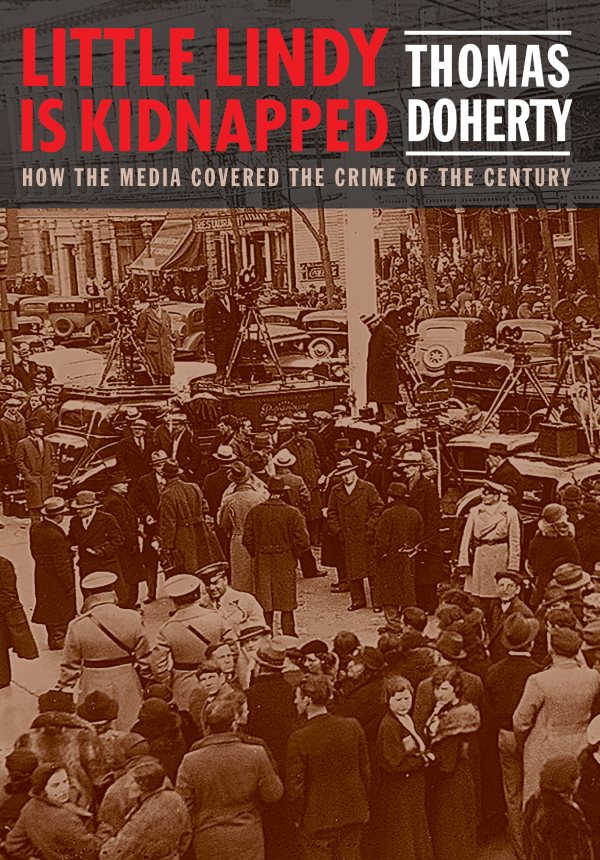

LITTLE LINDY IS KIDNAPPED

LITTLE LINDY IS KIDNAPPED

How the Media Covered the Crime of the Century

THOMAS DOHERTY

Columbia University PressNew York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2020 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-55265-3

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Doherty, Thomas, author.

Title: Little Lindy is kidnapped: how the media covered the crime of the century / Thomas Doherty.

Description: New York City: Columbia University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020009654 | ISBN 9780231198486 (cloth) | ISBN 9780231552653 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Lindbergh, Charles Augustus, 1930-1932,KidnappingPress coverage.

Classification: LCC HV6603.L5 D64 2020 | DDC 070.4/49364154dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020009654

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Front cover photo: Outside the Hunterdon County Courthouse in Flemington, New Jersey, the expectant crowd and the media await the jurys verdict in the Trial of the Century, February 13, 1935.

Back cover photo: Charles Lindbergh leaves the back entrance of the Hunterdon County Courthouse, Flemington, New Jersey, January 10, 1935.

CONTENTS

For Sandra

T his is a true media book not a true crime book. The detective work examines the ways the newspapers, radio, and newsreels covered what they rightly figured was the Crime of the Century, though they were still only one-third into it.

The guilt of the man executed for the crime remains, in some circles, a matter of controversy, but the justice of the verdict is the topic for a different book. To lay my cards on the table, I accept the conventional wisdomthat Bruno Richard Hauptmann planned the kidnapping of, and killed, either maliciously or through misadventure, the twenty-month-old son of Charles and Anne Lindbergh on the night of March 1, 1932. Yet anyone looking at the strange circumstances surrounding the case must admit that the kidnap-murder of the Lindbergh baby is a story that defies neat resolution, that to open the case files and sift through the evidence boxes is to get emmeshed in a web of loose ends and unlikely occurrences. Many of the smartest armchair detectives of the day, including criminal attorney Samul S. Leibowitz and journalist Adela Rogers St. Johns, believed that Hauptmann must have had at least one accomplice. I demur, but concede the possibility.

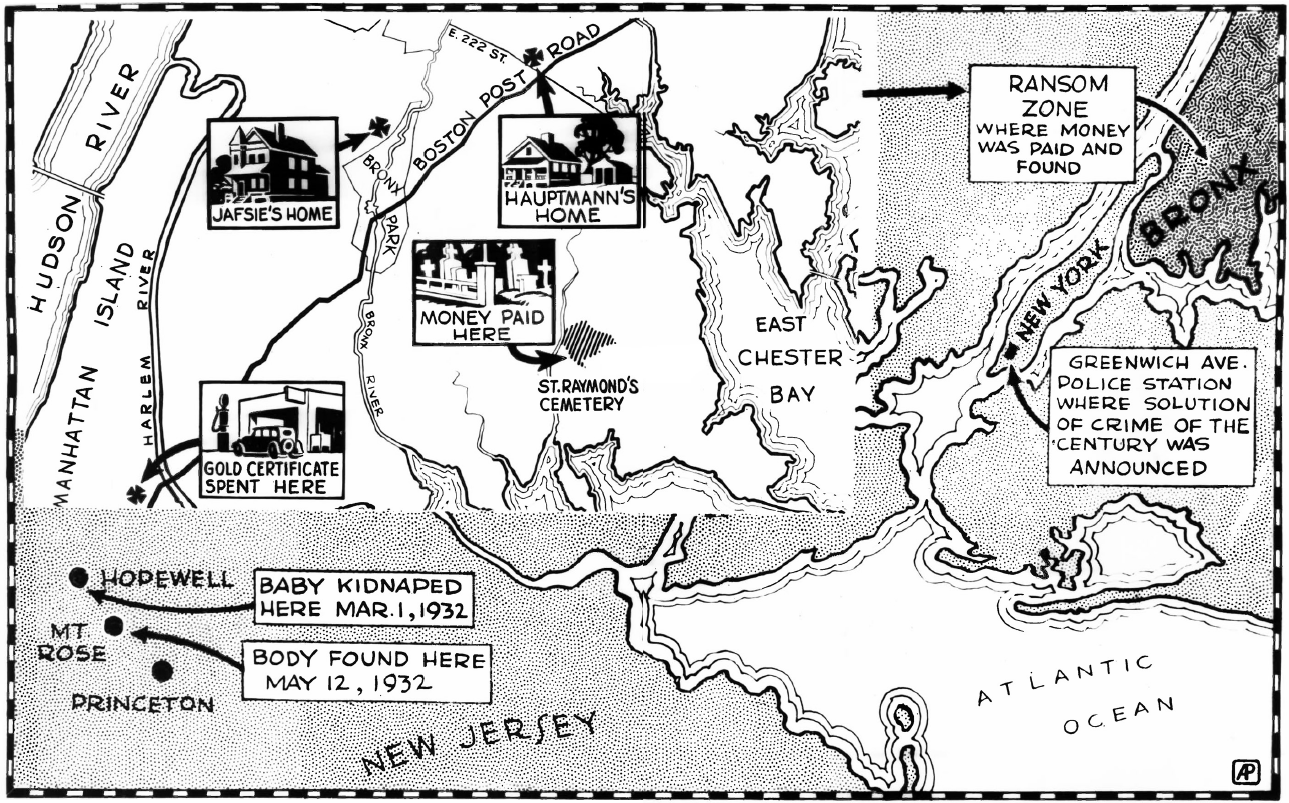

A map of the principal sites of the Lindbergh kidnap-murder published on September 20, 1934, after the capture of Bruno Richard Hauptmann.

Experts on the Lindbergh case will notice that I have not mentioned some signature incidents or followed up on some tantalizing clues. The metal thumb guard Betty Gow found while strolling down the gravel road at Highfield on April 1, 1932was it overlooked by the New Jersey state troopers, who overlooked so much, or was it planted for her to find on the day before Dr. John F. Condon exchanged the ransom money with Cemetery John? The address and phone number that belonged to Dr. Condon, written on a closet door in Hauptmanns Bronx homedid Hauptmann write it or was it planted by a malicious cop or newspaperman? I have not attempted to give a comprehensive, no-stone-unturned account of the Lindbergh caseto examine every piece of evidence found at the crime scene, every witness questioned, and every legal maneuver in the trial. I have streamlined the crime story to give the reader the background necessary to appreciate what I have foregrounded, the media story.

I hope readers who dissent from my approachand verdictwill nonetheless find the media story illuminating. For each of the three news lanes on the information highway, the Lindbergh case marked a transformative passage. Surprisingly, despite the many works chronicling the case, little has been written about the media angle of this most media-saturated of stories. The cultural historical synchronicity alone offers fertile terrain: the crime coincided with the tipping-point moment of penetration for radio and sound newsreels.

In tracing the media trail, I have also tried to evoke the emotions that Americans felt when following the news of the tragedy that had befallen the most beloved couple of the time. It would be nave not to acknowledge the tawdry voyeurism in the curiosity and the competitive exhilaration in the coverage, but it would be too cynical not to appreciate the sympathetic bond the story engendered on all sidesin investigators, journalists, and ordinary Americans who grabbed a newspaper extra, reached for the dial, or watched the newsreels in pity and horror. The news was taken to heart; it concerned the loss of a baby everyone knew by his nickname.

I n the spring of 27, recalled a wistful F. Scott Fitzgerald, still dazzled by the natural phenomenon from four years earlier, something bright and alien flashed across the sky, a meteor in the form of a young man who seemed to have nothing to do with his generation.

Fitzgerald meant that Charles Augustus Lindbergh was everything the Jazz Age was not: serious, traditional, and quietquietly professional, quietly determined, and quietly heroic, a self-made man who earned his wealth and fame not by investing on margin or coining advertising slogans or play-acting on the silent screen, but with an awe-inspiring feat of individual initiative and dauntless courage. In an age of crass ballyhoo and false gods, Lindbergh was the real McCoy.

A Thirty-Three-and-a-Half-Hour Vigil

At 7:22 A.M., on the drizzly morning of May 20, 1927, Lindberghtwenty-five years old, lean as a rail, movie-star handsometook off in a balsa wood monoplane from Roosevelt Field on Long Island destined for Le Bourget Field outside of Paris, a distance of 3,640 miles. He flew alone, and he flew nonstop. The blind plane had no direct field of vision ahead; the pilot depended on a periscope for forward orientation and looked out the side windows to get his bearings and make landings. Built just weeks before under Lindberghs supervision by Ryan Airways, Inc. of San Diego, California, the aircraft was named the Spirit of St. Louis, in honor of the consortium of pubic-spirited citizens from Missouri who bankrolled the enterprise. In the previous century, when humanity was still tethered to the ground, St. Louis had been the gateway to the American West, the starting point for pioneers embarking on a dangerous pilgrimage through Indian country. Lindberghs journey also broke a trail into a new frontierand history.

Born on February 4, 1902, in Detroit, Michigan, descended from flinty Swedish stock, Lindbergh was reared in Minnesota, the son of a prominent attorney, businessman, and Republican congressman and a schoolteacher. Too young to have served in and been disillusioned by the Great War, he fell in love with its terrifying new combat weapon and by age nineteen had earned his pilots license. Abandoning the study of mechanical engineering at the University of Wisconsin, he barnstormed across the Middle and Far West, thrilling crowds at county fairs and air shows with stunt flying and parachute jumps.