HOLLYWOOD AND

Hitler 19331939

FILM AND CULTURE

JOHN BELTON, EDITOR

FILM AND CULTURE A SERIES OF COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS FOR THE LIST OF TITLES IN THIS SERIES, SEE

HOLLYWOOD AND

Hitler 19331939

THOMAS DOHERTY

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

NEW YORK

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2013 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-53514-4

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Doherty, Thomas Patrick.

Hollywood and Hitler, 19331939 / Thomas Doherty

pages cm. (Film and culture)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-16392-7 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-231-53514-4 (ebook)

1. National socialism and motion pictures. 2. Motion picture industryUnited StatesHistory20th century. 3. Motion picturesPolitical aspectsUnited StatesHistory20th century. 4. Motion picture industryGermanyHistory20th century. 5. Motion picturesPolitical aspectsGermanyHistory20th century. 6. Motion pictures in propagandaGermanyHistory20th century. 7. Motion pictures, AmericanGermanyHistory20th century. 8. Motion pictures, GermanUnited StatesHistory20th century. 9. Nazis in motion pictures. I. Title.

PN1995.9.N36D65 2013

791.43094309'04dc23 2012046863

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover image: Song of Songs 1933 Paramount Productions Inc. Courtesy of Universal Studios Licensing LLC

Cover design: Lisa Hamm

References to Internet Web sites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

To SandraAgain

CONTENTS

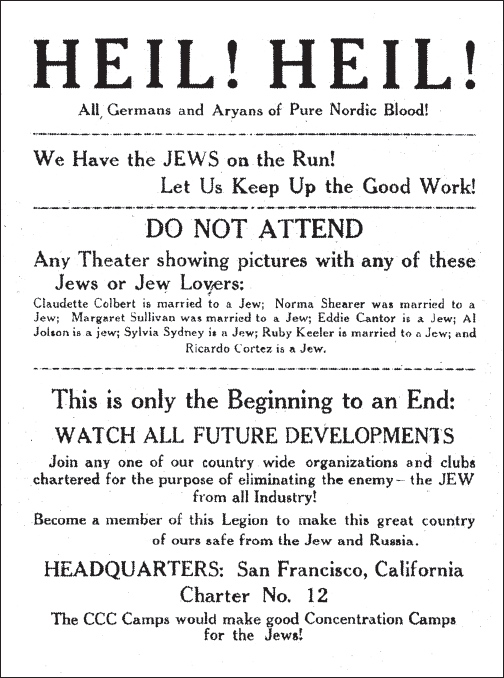

Homegrown antisemitism: a leaflet denouncing Hollywood Jews, 1936.

H ollywood first confronted Nazism when a mob of brownshirts barged into a motion picture theater and trashed a film screeninga resonant enough curtain-raiser, if a bit heavy-handed on symbolism.

On December 4, 1930, All Quiet on the Western Front (1930), Universal Pictures spectacular screen version of the international best seller by Erich Maria Remarque, premiered at the Mozart Hall, a showpiece venue in Berlin, the true capital of the Weimar Republic, the democratic federation founded in 1920 and hanging on by a slim thread ten years later. The antiwar epic was the first must-see film, not starring Al Jolson, of the early sound era. Only a few years earlier, Jolson had shattered the mute solemnity of the silent screen with the soulful racket of The Jazz Singer (1927), a technological marvel and cultural bellwether about an ethnic, religious, and racial chameleona Jewish boy in blackfacewho hits the big time in America, actually becomes American, by singing jazz and shaking his hips on the Broadway stage.

Only the clash of ignorant armies filled the soundtrack of All Quiet on the Western Front. Directed by Lewis Milestone, a Russian-born veteran of the U.S. Army Signal Corps, the somber death march kept faith with Remarques bitter perspective on the Great War, a wrenching tale of blithe cannon fodder led to the slaughter by dreams of glory and the lies of cynical old men. The film won top honors from a professional guild founded just two years earlier, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, garnering a pair of trophies not yet dubbed Oscar for Best Director and Best Production.

Remarques sentiments were shared by most of the people so lately in each others crosshairs: the real enemy was war, not Germany, England, or France, still less the United States, a tardy combatant who had emerged from the bloodbath relatively unscathed, the body count for its entire hitch in service not matching the deaths suffered by the British, French, and Germans at the Somme, or Verdun, or Pachendale. With a presold story and a heartfelt message, the international market for what critics and audiences alike hailed as a cinematic masterpiece seemed auspicious, nowhere more so than in Germany, the war-ravaged home of the author.

Yet since the January 1929 publication of Remarques novel, a bildungsroman steeped in the antiwar atmospherics of the Weimar Republic, a rival zeitgeist had swept over Germany. Led by a former corporal on the Western front, the most extreme of the right-wing militarist groups continued to fight for a noble cause lost only because the gallant warriors had been stabbed in the back by the Armistice of November 11, 1918, and crushed underfoot by the Versailles Treaty. For the Nazis, the Great War remained a festering wound and a powerful recruitment tool. The partys paramilitary wing, the Sturmabteilung (storm troopers, or S.A.)street thugs known by the brown color of their uniformstood ready to do battle, Armistice or not.

Anticipating a turbulent reception in Germany, Universal tried to head off trouble by soliciting prior clearance from Baron Otto von Hentig, the German consul general in San Francisco, who flew down to Los Angeles for a private screening at Universal Pictures.

The first public screening in Berlin augured well. Mirroring the reactions of American, British, and French audiences, the opening-night crowd at the Mozart Hall watched in quiet reverie. After all, like the book, the film was a deeply German story: of a patriotic young Gymnasium student, blazing with fervor for the Fatherland, who marches into carnage, disillusionment, and ultimately, inevitably, death, felled by a snipers bullet as he reaches over a parapet to touch a fluttering butterfly. The final image plays taps for the dead on all sides: a double exposure of fresh-faced, smiling recruits, looking back into the camera, not accusingly, just oblivious to what awaits them, over a field of graveyard crosses.