PITT SERIES IN RUSSIAN AND EAST EUROPEAN STUDIES

Jonathan Harris, Editor

Published by the University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, Pa., 15260

Copyright 2012, University of Pittsburgh Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Printed on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hicks, Jeremy.

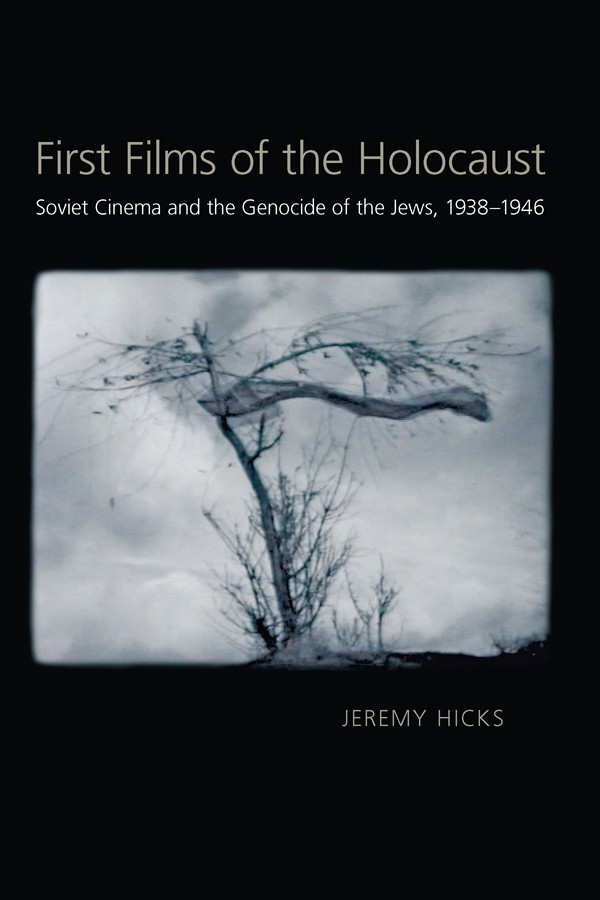

First films of the Holocaust : Soviet cinema and the genocide of the Jews, 19381946 / Jeremy Hicks.

p. cm. (Pitt series in Russian and East European studies)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Includes filmography.

ISBN 978-0-8229-6224-3 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Holocaust, Jewish (19391945), in motion pictures. 2. Antisemitism in motion pictures. 3. Jews in motion pictures. 4. Motion picturesSoviet UnionHistory. I. Title.

PN1995.9.H53H53 2012

791.43'652924dc23 2012030693

ISBN-13: 9780822978084 (electronic)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book emerged from two sources. One primary origin lay in conversations with Howard Jacobs, whom I was lucky enough to teach; with Libby Saxton, a colleague at Queen Mary, University of London; and with Evgenii Tsymbal, a visiting scholar there. The other source was a chance discovery of documentary film footage relating to the Holocaust in the Russian documentary film archive (RGAKFD, Krasnogorsk). First and foremost, I owe a personal and intellectual debt to these people, as well as to that archive; its staff, especially Elena Kolikova; and the archives director, Natalia Kalantarova.

Once formulated, this research project would not have been realized as a book without the generous and gracious funding of the Philip Leverhulme Trust, enabling me to devote myself to research in the 20092010 academic year. Equally important has been the support from individuals in various quarters of Queen Mary: my immediate colleagues in the Russian department, Andreas Schnle, Anna Pilkington, and Olga Makarova; Rdiger Grner, in the wider School of Languages, Linguistics and Film; and others in the college more generally.

Other than the RGAKFD, a number of Russian archives have provided generous assistance to me in the pursuit and completion of this project. In particular, I would like to thank the staff of the RGALI, especially Dmitrii Neustroev and the director, Tatiana Goriaeva; Gosfilmofond, especially Valerii Bosenko and its deputy director and guiding light, Vladimir Dmitriev, who kindly gave me lifts, as well as its current director, Nikolai Borodachev; the Museum of Cinema (Moscow), especially Emma Malaia and the director, Naum Kleiman; and the GARF and RGASPI. British film collections have been no less accommodating to me, and I would like to thank the IWM (especially Matthew Lee), the BFI, and the National Film and Television Archive. I have also benefited enormously from the University College Londons School of Slavonic and East European Studies Library, the British Library, the Russian State Historical Library (Istorichka), the Russian State Library (Leninka), and the British Film Institute Library.

Friends who have helped me obtain materials and aided me in other ways include Evgenii Margolit, Nikolai Izvolov, Aleksandr Deriabin, Sergei Kapterev, Crispin Brooks, Barbara Wurm, and John Haynes. Other academic colleagues who have helped by commenting constructively and productively on various parts of this work include Karel Berkhoff, David Shneer, Olga Gershenson (whom I thank for sharing her thoughts with me and for her helpful critique of the errors in an earlier version of ), Natascha Drubek-Meyer, Valrie Pozner, Ilia Altman, Valerii Fomin (even though he disagreed with the project), Julian Graffy, David Gillespie, Gil Toffell, Stuart Liebman, the members of the SSEES Russian Cinema Research Group, and participants at the numerous conference panels where I have given earlier versions of parts of the book. I would also like to thank Peter Kracht and the University of Pittsburgh Press for the interest they have shown in this project and the anonymous readers, especially the second one, whose comments helped me strengthen the book considerably.

I would also like to thank Valrie Pozner, Birgit Beumers, and Dieter Steinert for permitting me to reproduce reworked versions of previously published material in chapters .

As with all my work, I owe an unpayable debt to Inger and Nina, who have endured, inspired, and sustained me.

I would like to dedicate this book to the memory of my friend Pete Glatter, who made me think.

A NOTE ON TRANSLITERATION

In the text, I follow Library of Congress transliteration standards except for a few famous Russian names, where I have used the familiar form. Thus, instead of Ilia Erenburg, it will be Ilya Ehrenburg. The bibliography and endnotes, however, follow the Library of Congress norms throughout.

I have also employed Russian versions of Ukrainian proper names, without diacritical marks, in the main text, because they are the forms most familiar to Western readers. I include myself in this number, as the greater part of my sources are Russian or English, not Ukrainian. Thus, I shall refer to Aleksandr and not Oleksandr Dovzhenko, to Kharkov and not the Ukrainian version Kharkiv, and likewise to Kiev and Babyi Iar, not Kyiv and Babyn Iar.

Unless otherwise attributed, all translations are my own. Consequently, most of the film titles in the book are my own translations from Russian, and the reader may encounter them elsewhere in slightly different translations.

Introduction

For many, the Holocaust has become the most important historical event of the twentieth century. Indeed, it has become part of the American experience, providing Americans a point of reference firmer even than the Civil War or Pearl Harbor. As an extreme of human behavior, it informs not only the understanding of history but also contemporary politics as the international community strives to comprehend, prevent, or prosecute programs of genocide, a term itself coined to describe the Nazis attempted extermination of the Jews.

Images, especially cinematic ones, have been a crucial means for inculcating public awareness of the Holocaust. Indeed, widespread Western skepticism about Nazi crimes was decisively defeated by screening newsreels of the camps at the end of the war. More recently, several popular films, including Marvin J. Chomskys Holocaust television miniseries (1978) and Steven Spielbergs Schindlers List (1993), further raised mass consciousness about the Holocaust. While these are reconstructions, audiences are also familiar with fragments of the original newsreel images, which have been recycled for both authorial films, such as Alain Resnaiss seminal Night and Fog (Nuit et brouillard [1955]), and TV documentaries, such as the final two parts of Thames TVs 1973 World at War (The Final Solution, directed by Michael Darlow), to name but two.

Yet rarely do we pause to reflect on the genesis of the newsreel images. This oversight masks an extraordinary ignorance about the first moving images to depict the Holocaust not taken by perpetrators themselves. These little-considered films were made and shown before the newsreels showing U.S. and British soldiers liberating camps in Germany in 1945, usually regarded as the first films of the Holocaust. The neglected imagesSoviet wartime filmsare cinemas initial attempts to represent the Holocaust, the subject of this study.