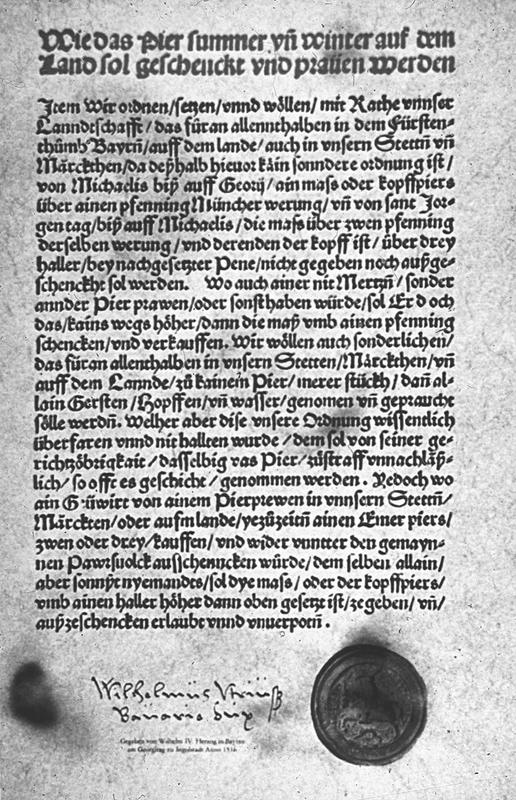

Europeans have long enjoyed their beer so much so that authorities through the ages have seen fit not only to tax it but also to legislate its production. The German Reinheitsgebot, or purity law, enacted in the Bavarian city of Ingolstadt on the 23rd of April 1516 and reaffirmed on many occasions since, stipulates that beer may be brewed from only malted barley, water and hops. This regulation, however, is underpinned by a truly ancient tradition, and the history of beer extends far beyond the boundaries of Europe.

People noticed early on that sprouted grain could become converted to sugars and fermented. The history of beer stretches back as far as humans have engaged in agriculture. Modern research methods have shown that Stone-Age earthenware vessels discovered in the highlands of Iran were used for storing sprouted and fermented grain. While the first instance of malting and fermentation may well have happened by accident when a pot of grain got damp, people soon noticed the good results of fermentation and learned to use them to their advantage. Archaeologists agree that many of the vessels discovered were used expressly for making beer rather than containing malted mash that had happened to start fermenting.

It has even been hypothesised that the skill of making grain into malt and brewing it into beer is what brought yeast into widespread use, so that beer was accompanied on the table by leavened bread. If that is the case, then beer is even older than bread as a basic human foodstuff.

The Sumerians described drinking beer as early as 4000 BCE, and the first recipes explaining how to brew beer from malted grain and pure water date from the third millennium BCE. The cultivators of the fertile fields of Mesopotamia with their elaborate irrigation systems produced and consumed large quantities of beer, which soon became a major commodity. Mesopotamia is where we also find the oldest known regulations concerning the serving and pricing of beer, as well as references to beer playing a role as the inspiration for many significant projects.

Law 108 of the Code of Hammurabi from the 18th century BCE stipulates that beer is to be priced in units of grain, and any tavern-keeper who overcharges for beer that is, who charges more than the price for the equivalent amount of grain shall be thrown into the water. Whereas many have waxed lyrical and philosophised about the effects of wine, beer has been the source of great plans. Law 109 of the Code of Hammurabi states that a tavern-keeper who permits conspirators to assemble under her roof without capturing them and delivering them to a court shall be put to death.

In Egypt under the pharaohs, long home to a great many grape vines, beer was considered to be the tipple of drunkards. Many papyrus scrolls preserved to this day contain rebukes of beer-filled revelling in the streets deploring the stench they left behind in the narrow lanes of Egyptian settlements.

As civilisation spread from Egypt to Greece, the Hellenes considered beer to be an entirely barbaric beverage. The Romans shared that view, as grape vines have always produced ample harvests under the benevolent Italian sun. The mere fact that beer was made from barley, which the Romans regarded as animal fodder, rendered it suspect to them. So its no wonder the Romans considered the Celtic tribes of Gaul and later the Germanic tribes to be utterly uncivilised, as they enjoyed drinking beer made from barley.

In the first century CE the Roman historian Tacitus wrote in his Germania of the Germanic people, who drank large quantities of beer while making decisions in matters of war and peace or when deciding on major matters such as sentencing a member of the tribe to death, and then reconvened the following morning to consider the matter again. If they still thought the decision seemed right, it was then implemented. When Tacitus informed his readers by describing beer as barley juice quodammodo corruptum spoilt in a particular way he was reinforcing the view, widely held in southern European cultural circles, that beer was not a particularly refined tipple.

During the turbulent times following the fall of the Roman Empire, characterised by mass migrations and famines, food and drink culture meant simply having enough to eat. In the early Middle Ages the Catholic Church, having inherited a substantial share of the vanished empires prestige as well as propagated the machinery of its bureaucracy throughout Europe, carried on many Roman traditions. Thus the view of beer as a vulgar, even barbaric, drink was preserved through the centuries. In a way, the ancient division between the wine- and beer-drinking parts of Europe is still evident today. The core areas of the old Roman Empire are still wine-drinking lands, while those termed beer-drinkers by Julius Caesar and Tacitus including the British, the Belgians, the Germans and the Nordic countries continue to drink beer.

Even now beer is sometimes left to bear the label of a bulk product suitable only for intoxication. Those who share that opinion easily forget the diversity of the world of beer, basing their views on cheap, weak lagers which are brought home from the market in the car boot in packs of six, twelve or twenty-four cans.

But beer is also much more than that. This book presents anecdotes from throughout the centuries when beer played a decisive role in the course of history. We also aim to highlight the central role of beer in European culinary cultures and customs, as a source of inspiration and even a facilitator of friendships between nations.

In the twenty-four chapters in this book, we present beer in the context of cultures, ideas, social changes and economic circumstances in different eras. The stories come from all over Europe, ranging from the early Middle Ages to the twenty-first century. At the end of each chapter, we give a more detailed description of a particular beer that is linked to the events described in the chapter. Many of them are available outside their place of origin, so you can experience the frothy history of Europe through your nose and taste buds as well.

And so wed like to welcome our readers on an enjoyable excursion through the history of beer. Cheers!

21 April 2014

The authors

To stop things getting too dry

In this book we present some background information on the beers mentioned, their connection with the events described in each chapter, their style and characteristics.

ABV : The percentage of alcohol content by volume.

GRAVITY : In mashing germinated grain, or malt, the proportion of the total wort mass that is made up of dissolved sugars. The sugar in the wort is turned into alcohol by the addition of yeast, so in practice a higher gravity will produce a higher alcohol content. This is expressed using the Plato scale (e.g. 10P means that 10% of the wort mass is sugar.)

BITTERNESS : The bitterness from hops in beer, measured according to the EBU scale (EBU = European Bitterness Units). The higher the value, the greater the bitterness.

COLOUR : The hue of the beer, measured according to the EBC scale (EBC = European Brewing Convention). The higher the value, the darker the beer.

The table below lists the values for four well-known beers from Finland, our home country.

| Karjala (brewed in Lahti) | Sandels Tumma (brewed in Iisalmi) | |

![Willis - Beer: a cookbook: good food made better with beer: [recipes]](/uploads/posts/book/224368/thumbs/willis-beer-a-cookbook-good-food-made-better.jpg)