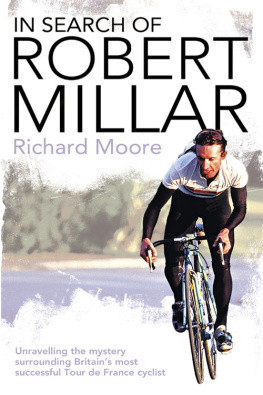

I can remember, quite clearly, my first encounter with Robert Millar. It was at lunchtime on Saturday, 21 July 1984. I was 11 at the time. Robert Millar will remember the occasion more vividly, because while I was watching television with my dad in my familys living room, he was in the Haute-Arige area of the Pyrenees, climbing a steep, winding road that ended at the ski station at Guzet Neige the finish of stage 11 of the Tour de France.

We had recently moved to England from Scotland, and my Scottishness was being pointed out to me repeatedly. A PE teacher nicknamed me Jock, and it stuck. I hated being singled out. On the other hand, I quite liked it too. But I was desperately, urgently looking for allies namely, fellow Jocks wherever I could, even on television, even participating in obscure sporting events. I looked at the TV screen but couldnt really work out what was going on. There was a small group of sweating cyclists straining against a steep gradient and suffering in the blazing heat. So this was the Tour de France. It looked pretty boring.

I asked my dad, who was receiving his weekly fix of the Tour de France on ITVs World of Sport, whether any Scottish cyclists were competing in this strange event. There is one Scot, he replied, a note of surprise in his voice. Robert Millar, from Glasgow. Thats him there.

Now I was interested. I was struck by the name, by its ordinariness. He didnt sound like he belonged there. Robert Millar jarred alongside the exotic-sounding Laurent Fignon, Bernard Hinault, Pedro Delgado, even the American with the French-sounding name, Greg LeMond. And yet, although I didnt know it at the time, in the wiry, compact form of Robert Millar I had just stumbled upon someone who was not only Scottish but most certainly and defiantly different; someone who didnt just mind standing out, or apart, from the crowd, but actually seemed to want to.

Will he win? I asked.

No, said my dad, with good old-fashioned Scottish pessimism-realism.

But Dad was wrong, or at least partially wrong. I kept watching. I can vividly recall the footage of the Tour on that particular day, with commentary that sounded like it was coming from outer space. The grainy quality of the pictures and the sounds made the broadcast seem other-worldly. It was, in fact, less like watching sport and more like witnessing astronauts landing on the moon, or mountaineers arriving at the summit of Everest. And I remember Millar winning the stage, his second Pyrenean victory in consecutive years, on his way to claiming one of the races three great prizes, the title of King of the Mountains. He was the first and to this day remains the only English speaker ever to wear the fabled polka-dot jersey awarded to the King of the Mountains all the way to the finish in Paris.

There was something about Millar, quite apart from his nationality and the fact that he was beating these foreigners at their own game, on their own turf, to the top of their own mountains, that was instantly fascinating. As he climbed the mountain his head bobbed gently and easily to the rhythm of the pedals. His style was unusual but fluid and efficient. His left knee flicked in and then out at the top of the pedal stroke, following a consistent, smooth pattern. His eyes were focused a few yards in front, yet they also appeared vacant, expressionless, drawn with the effort the face of a hungry man, according to the commentator, Phil Liggett.

That Saturday afternoon Millar was in the company of three other cyclists, but when the slope reared up, he was the one doing most of the pace setting. He seemed to be teeming with nervous energy, repeatedly looking over his shoulder, checking the others, cajoling them even. While he was fleet of foot, they were leaden by comparison; the slender, lightweight Scot looked as if he might fly off at any moment, the others as if they would be dragged back down the hill by the pull of gravity. I hope he doesnt overdo it with his confidence, said the partisan Liggett, as if trying to send the Brit subliminal messages.

Then, as they approached a sweeping left bend, Millar took flight. He stood up on the pedals and accelerated into the crowd, his bike swinging violently from side to side, his body bobbing up and down with urgency, releasing all that pent-up energy in a bid to shake off his companions, now down to two, a Frenchman and a Dutchman. Neither reacted; if anything, they seemed relieved to see him flee, glad of an excuse to slow down. Ahead of them Millar forged on, relaxing into that gentle, easy rhythm. In the commentary box, Liggett wasnt so calm: Hes not a big-headed man at all, but when you speak to him confidence oozes out of him. Several times he highlighted the incongruity of a cyclist from Glasgow excelling amid such company, and in such terrain. He was a little worried that this stage wouldnt be hard enough for him, Liggett added with a chuckle.

Inside the final kilometre of the 226.5km stage, Millars hand dipped inside the back pocket of his jersey and emerged clasping a white cap bearing the name of his team sponsor, Peugeot, which he then stuck on his head in one fluid movement. The little man from the Gorbals with the big heart and the powerful legs, screamed Liggett, his voice crackling with emotion, as Millar climbed towards the finish. Millar has unleashed all his anger today on the Tour de France.

Behind Millar, Luis Herrera and Pedro Delgado, late attackers, had leapfrogged his earlier companions; he had escaped at just the right time. But now they were chasing, and closing. They were within a minute; Millar had to sprint as if he was launching his initial attack all over again. But in the final metres, when he knew he had won, Millar appeared to relax, sitting upright, taking his hands off the handlebars, raising them, allowing his clenched fists to fall behind his head, then pumping them back into the air, palms open, eyes looking down rather than at the photographers, but face smiling. The clock stopped at seven hours, three minutes and forty-one seconds as he crossed the line. Seven hours! And he was sprinting! Uphill! It was inconceivable.

Then, his peaked cap framing his gaunt face, giving him the appearance of a jockey in need of a good feed, Millar faced what was for him the bigger ordeal: the post-race interview. Liggett asked the questions. What had gone through his mind on that final climb? That I was gonna win, that I knew I was gonna win, and that I was really happy, mumbled Millar, wearing a blank expression apart from the thinnest of smiles forming on his lips. He had known virtually the whole stage that he was going to win, he added, and he was certain after the climb of the Col du Portet dAspet, when he was the strongest in the leading group. At the end of each sentence he seemed to add an eh virtually the only trace of a Scottish accent in his curious hybrid drawl. He proved as fascinating to watch during this interview as he had been during the race. He was a mass of contradictions, appearing self-assured yet nervous; possessed of steely confidence yet impossibly shy; in control yet awkward. He spent much of the interview looking away from the camera, away from his interrogator, but when he briefly glanced up his eyes burned with intensity. Or was it anger, as Liggett had suggested? At the same time his face twitched and his brow contorted with apparent nervousness.

Cycling became my sport, Robert Millar my hero. His seemed to be the ideal identity for a displaced young Scot to assume in a strange foreign land: suitably different, possibly cool, certainly interesting. I was given a glossy coffee-table-style book,