This book has profited from the expertise of several friends and colleagues. David Konstan has provided astute observations on a variety of issues, with his customary wit and a light touch. Christopher Pelling has painstakingly read an early draft of the entire manuscript; without his sharp and encouraging comments this book would not be what it is. Susan Prince has generously made available to me the bulk of her yet unpublished work on Antisthenes and has read . Paula Gottlieb has shared her impressive knowledge of Aristotle with me. Ullrich Lange has read the epilogue; William Aylward has provided precious bibliographical references on Odysseus in ancient art. I should also like to thank two anonymous readers for their helpful comments.

Sections of this book have been inflicted on audiences both in the United States and in Europe: it would take too much space to thank by name all who gave me the opportunity to test my ideas, but please accept the expression of my gratitude. Thanks also to Ellen Bauerle for welcoming my work to the University of Michigan Press; to the staff of the Press for their patience; and to Monica Signoretti for help with the indexes. Finally I dedicate this study, with love, to Gareth Schmeling, for his love and support. In spite of his aversion to anything philosophical, he has put up with the author of this book during its gestation with truly philosophical, and Odysseus-like, forbearance.

ABBREVIATIONS

ANRW: W. Haase and H. Temporini (eds.), Aufstieg und Niedergang der Rmischen Welt, Berlin, 1972

DK: H. Diels and W Kranz (eds.), Die Fragmente der Vorsokratiker, 6th ed., 3 vols., Zurich, 199698

LSJ: H. G. Liddell and R. Scott (eds.), Greek-English Lexicon, rev. H. S. Jones, 9th ed. Supplement, Oxford, 1968

PCG: R. Kassel and C. Austin, Poetae Comici Graeci, 8 vols., Berlin, 19832001

RE: Paulys Real-Encyclopdie der Klassischen Altertumswissenschaft, Stuttgart, 18941919

SSR: G. Giannantoni (ed.), Socratis et Socraticorum Reliquiae, 4 vols., Naples, 198390

SVF: H. von Arnim (ed.), Stoicorum Veterum Fragmenta, 3 vols., Leipzig, 19035

TGF: R. Kannicht, S. Radt, and B. Snell (eds.), Tragicorum Graecorum Fragmenta, 5 vols., Gttingen, 19712004

TLG: Thesaurus linguae graecae. A digital library of Greek literature, Berkeley, 2004

INTRODUCTION

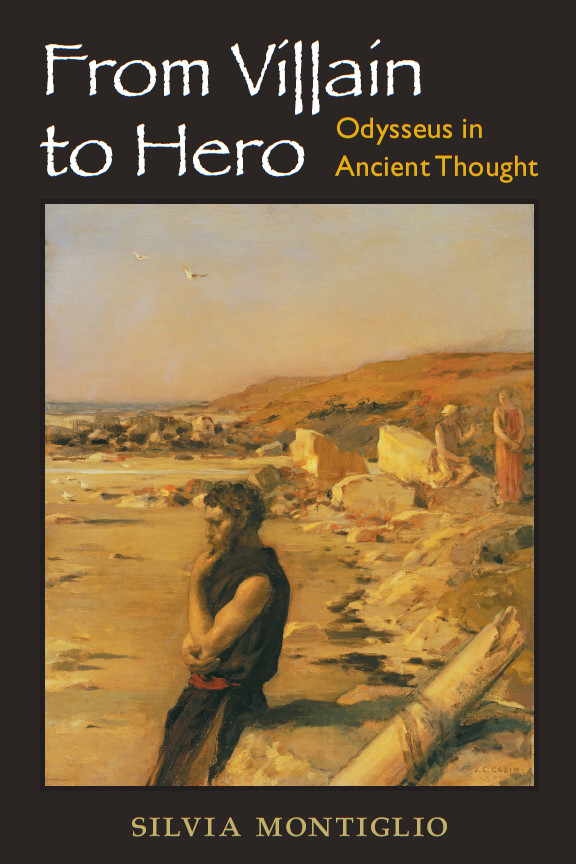

The philosopher: such is the name the twelfth-century Byzantine bishop Eustathius time and again gives Odysseus. The man of many turns, the most versatile of all Greek heroes both in Homeric epic and in his later incarnations, by the twelfth century could also boast of a long journey across philosophy, and one that was bound to continue, down through the ages, even to the modern world. The goal of this study is to map a small portion of that journey: Odysseus philosophical adventures in the core period of ancient thought.

From the late fifth century onward, among Odysseus many roles that of the wise man stands out as one of his most compelling performances. Yet no full-scale study of his philosophical impersonations exists. W B. Stanford in his now classic book The Ulysses Theme devotes one chapter and a number of scattered observations to philosophical treatments of Odysseus, but does not go into much detail. Odysseus, however, was exploited and discussed across the philosophical spectrum. No comprehensive examination of these treatments of Odysseus is available, to show the articulations, the elements of continuity and of change, in his philosophical history.

But one might ask: after all, are we justified to single out philosophical readings of Odysseus and devote a separate study to them? An approach driven by moral concerns characterizes interpretations of Odysseus both in philosophical texts and outside philosophy. Every refashioning of him in ancient literature is at the same time a moral evaluation; and each and every picture produced by creative authors is reductive compared to the richness of the Homeric character. Odysseus becomes the deceitful speaker (as in Pindar), the skilled but ruthless politician (as in several tragedies), the glutton (in several comedies), and so forth. We witness something of a paradox: the most complex of Homeric heroes in his post-Homeric reconfigurations is cut into pieces, as it were, and judged for one of his traits. This fragmentation is not simply owing to the tendency of post-Homeric authors (except, we can assume, for the poets of the Epic Cycle) to treat only one episode in Odysseus career rather than many, as in the Odyssey, but is connected to the Growing Hostility (as Stanford entitles chapter 7 of his book) against our hero, which can be traced as far back as Pindar or possibly earlier. Odysseus character, because it invites more and more questions about its goodness, fails to preserve its multifaceted Homeric turns.

In that he becomes close to a type, the nonphilosophical Odysseus rubs elbows with his philosophical counterpart(s). In philosophical texts, however, in addition to serving as the representative of certain character traits, Odysseus serves as illustration of doctrine. He is not merely judged but also utilized to expound a theory or a model of behavior (to be followed or not). Seneca polemically engages with these philosophical exploitations of Odysseus in Ep. 88, in which he blames every school for appropriating Odysseus as the mouthpiece of its tenets. Philosophers found Odysseus good to think with: it will be the main task of this study to investigate how.

HEARING BLAME OF ODYSSEUS: AN ATHENIAN PLEASURE

A second characteristic of philosophical readings of Odysseus, as opposed to strictly literary ones, is that they are generally appreciative of him. From Socrates to his direct disciples as well as his more remote descendants, Cynics and Stoics, from the Epicurean Philodemus (first century BC) to Cicero, Seneca, and Plutarch, Odysseus seems more apt than any other hero to incarnate each philosopher's moral ideals.

Why then does Odysseus come to impersonate the wise man? To attempt an answer, we might benefit from looking at the essential features of the nonphilosophical portrayals of Odysseus that were circulating when philosophers firstadopted him as their hero. The treatment here will necessarily be summary: it will focus only and briefly on fifth-century portrayals and in particular on shared perceptions about Odysseus as we can infer them from those portrayals, for it is with such perceptions that Socrates and his followers, including Plato, seem to have actively engaged at the beginnings of Odysseus philosophical history. More background detail, when relevant, will be offered in the course of the discussion in the individual chapters.

Printed on acid-free paper

Printed on acid-free paper