Mythos and Voice

Mythos and Voice

Displacement, Learning, and Agency in Odysseus World

Charles Underwood

LEXINGTON BOOKS

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Lexington Books

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB

Copyright 2018 by The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

All rights reserved . No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018954724

ISBN 978-1-4985-3424-6 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4985-3425-3 (electronic)

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

To Ali

Contents

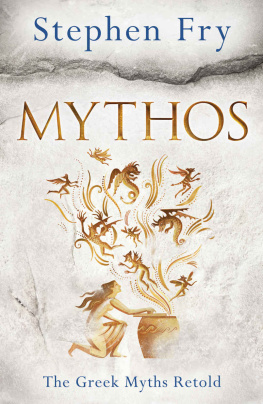

Midway through the epic narrative that bears his name, Odysseus wakes up in Ithaka. For the entire second half of the Odyssey , the epic tale of a mans interminable wandering, the main character is at homeand yet, he is not at home. He is a stranger in his own country, a man displaced from his own home and his own familya man who must find his way to relocating and redefining himself as himself, yet not his former self, but a new, cumulative self not unconnected from his former identity, but integrated as a combined version of both the old, familiar Odysseus whom his people vaguely recall and the newly arrived, largely unfamiliar stranger who now stands in their presence. The structure of the epic narrative impels us to recognize that the legendary journey of this mythic character, already famous at the time of the epics telling, is not simply a tale of voyaging through geographical and supernatural hazards; it is the story of a mans journeya soldiers precarious return after the trauma of warto find himself again among his own people. It is at the same time the story of his wife and son, of their social displacement from the roles they had formerly presumed to be their birthright within their own household, and of their respective journeys to resolve the disruption of their lives.

While these journeys are carefully interwoven into a larger epic frame, the story is told largely through the voices of its many characters. From this perspective, the Odyssey is a mythic journey in the original sense of the term; it is a journey that is performed and accomplished through mythos literally, speech or utterancewhat is said or what one says. It is a journey told in the various speeches and utterances, situationally presented by multiple voices, multiple characters, each with his or her own story, his or her own manner of speakinga polyglossal act of meaning-making framed by formulaic media to offer a multivoiced, sometimes cacophonic, yet ultimately coherent telling of a human beings journey among other beings, both human, subhuman, nonhuman, and supernatural. The telling itself constitutes an inclusive mythos , an overarching narrative that consumes and assimilates countless variant local tales and legends and incorporates them into a sprawling epic telling, spoken, or perhaps sung, in the distinctive voice of a master storyteller.

The mythos of the Odyssey , I would suggest, is a cultural production of displaced voices. The main characters all begin from a situation of displacement. Even the suitors may be seen as displaced aristocrats, lacking their own locus of authority and so pursuing a relatively secure placementas king of Ithakain an insecure world. Their tenuous position, vying against each other in Ithaka, is in some ways similar to that of Odysseus among the Phaiakians. Like other characters in the Odyssey , they are striving, primarily through discursive interaction, to assert themselves and insert themselves into the fabric of local society. Unfortunately for them, they are a bit thoughtless, even reckless, about it, as the poet explicitly notes. On the contrary, Odysseus act of telling his own story is not only a discursive act of self-definition and self-assertion, as Hartog (2001, 2017) has suggested. It is also an act of self-discovery and recovery. It is a process of reentry into human society in which the narrator for the first time is taking part in a culturally defined social activitythe guests socially obligatory telling of his geographical origins and his peoplein other words, the stranger-guests elaboration of his own participation in the humanity he holds in common with his audience. Through the enactment of his narrative of displacement and recovery, the guest verbally enacts his shared humanity.

Through his participation in the narrative performance before his audience, the narrator delineates both what he shares with his audience and what distinguishes him from his audience. It is as such not only a process of self-identification but also a process of progressively transforming the nature of his participation among them. That is, he is transforming his status among his hosts from a suspect stranger to a legitimate guest. In the process, he is as a narrator both successively revealing the defining features of his own background and astutely reading the cultural viewpoint (the habitus or the implicitly shared collective sense of thingsin Homeric Greek, the nos ) of his audience. The proem of the Odyssey has already announced this process as a major aspect of Odysseus engagement in the epic story by the expression: He had seen many peoples cities and came to see their views.

In short, Odysseus act of telling his story among the Phaiakians, as both an act of self-declaration and self-recovery, is a learning process for the narrator himself. We can interpret this process in light of Laves (1996) definition of situated learning as changing participation in sociocultural activity and Rogoffs (1995) analysis of this transformation as a process of participatory appropriation. For Odysseus, this process is an integral part of his learning process in returning to Ithaka. It represents the essential test by which he is able to establish himself as an appropriate guest, responsive to the generosity of his hosts and evidently responsible as a potential host to his audience in the event of their traveling to his homeland at some time in the futureand thus worthy of the safe conduct and transport to his home that he is requesting from them. Yet this narrative process of self-definition and self-recovery is also a very difficult learning process for the narrator. In telling his story, he necessarily has to face up to the trauma of his displacement; and although he tries to hide his irrepressible tears as he listens to Demodokos tale of his role in the Trojan conflict, he cannot keep himself from crying, not like a brave soldier facing danger or death, but like the hopeless wife of a soldier who has been killed in battle and who is destined for slavery or worse and his sorrow and pain are inevitably noticed. As Hartog (2017) notes, his sorrow is in part the shock of a man hearing his own obituary or posthumous account of his presumed former existence. But it is also the trauma of his displacement that occasions his uncontrollable sobbing. It is an expression of the social and emotional distance that Odysseus has yet to travel, in addition to the geographical and psychic distance he has already traveled, to reach his own country and his own people.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.