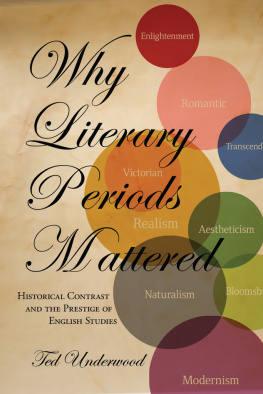

WHY LITERARY PERIODS MATTERED

Historical Contrast and the Prestige of English Studies

Ted Underwood

STANFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

Stanford, California

Stanford University Press

Stanford, California

2013 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Stanford University Press.

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Underwood, Ted, author

Why literary periods mattered : historical contrast and the prestige of English studies / Ted Underwood.

pages cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8047-8446-7 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. English literaturePeriodization. 2. English literatureStudy and teachingHistory. 3. English literatureHistory and criticismTheory, etc. I. Title

PR25.U53 2013

820.9dc23 2013010532

Typeset at Stanford University Press in 10/14 Minion

ISBN 978-0-8047-8844-1 (Electronic)

Contents

Acknowledgments

This book took a decade to write and went through major changes, so many of the people mentioned here may not recognize their contribution to its current form.

But at various stages of composition, I relied on advice from Nancy Armstrong, Marshall Brown, Walter Cohen, Anne Frey, Andrew Goldstone, Lauren Goodlad, Ryan Heuser, Matthew Jockers, Bob Markley, Jan Mieszkowski, David Suchoff, Matt Wilkens, Paul Westover, and Gillen Wood. Emily-Jane Cohen and Adam Potkay gave particularly crucial kinds of advice that reshaped the structure of the book. Eleanor Courtemanche listened to the whole argument as it evolved, and reminded me of evidence I was overlooking or suppressing.

The third chapter would have been impossible to write without assistance from the College Archives of University College, London, and Kings College, London; travel to those archives was supported by a William and Flora Hewlett International Research Travel Grant. Parts of were aired first in Philosophy and Culture, edited by Rei Terada for Romantic Praxis. Composition of the book was supported by sabbaticals from Colby College and from the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign.

John Unsworth deserves special acknowledgment for encouraging me to explore digital modes of literary research; without that encouragement, appeared earlier in The Journal of Digital Humanities. Work on this portion of the project was supported by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Where things digital are concerned, I should also credit Artificial Intelligence Atlanta, a small start-up that gave me my first programming job (in Prolog) some thirty years ago.

Introduction

Historical Contrast and the Prestige of Literary Culture

Histories of literary study tend to emphasize theoretical controversy. The subtitle of Gerald Graffs influential Professing Literature may be An Institutional History, but even Graffs book is in practice organized around methodological debatenotably the long debate between scholars and critics.torian of science, or East Asia, for instance, may regularly teach courses that cover several centuries. But more importantly, even when historians areas of specialization cover a relatively brief span of time, the temporal period tends to be secondary to a topic or problem that defines it. A historian might identify as a scholar of British imperialism, for instance, where literary scholars identify as Victorianists or modernists.

The contrast between literary studies and history may suggest that periodization is a by-product of professional specialization. It is true that present-day literature departments tend to have more faculty covering certain parts of the world than departments of history do. But the imperatives of professional specialization cannot explain the nineteenth-century emergence of a periodized curriculum. Period surveys preceded professional specialization by almost fifty years. They emerged in the 1840s, in literature departments that contained only one or two professors, who usually had to abandon the goal of synoptic coverage in order to make room for courses tightly focused on individual periods. Moreover, invoking specialization would not explain why periodization has so long remained the dominant mode of specialization in literary studies, instead of giving way to some other mode of specialization organized around a more properly literary category, like genre.

Periodization has endured in a discipline where almost nothing else does, and has endured not just in broad outline but in detail. One can open course catalogs from the late nineteenth century and find courses on English Romanticism and Elizabethan Drama that have been offered with essentially the same titles for a hundred and twenty years, while philology, the history of ideas, New Criticism, psychoanalysis, structuralism, and New Historicism came and went. Of course, the content of these courses was transformed whenever one methodology gave way to another. Different theoretical schools have defined the purpose of literary study in fundamentally different ways. But this is just what seems remarkable: the persistence of an organizing grid that is able to survive repeated, sweeping transformation of its content. Since professors have apparently felt free to change everything about their courses except the periodizing title, one begins to suspect that the value of literary study, in the eyes of students and of society at large, has been durably bound up with its ability to define cultural moments and contrast them against each other.

That is the suspicion this book explores: I will argue that an organizing principle of historical contrast has been central to the prestige of Anglo-American literary culture since the early nineteenth century, although its authority is now in decline. Two phrases in that sentence may need to be unpacked. The prestige of literary culture encompasses claims about literatures cultivating influence on readers both inside and outside the academy. Historical contrast was already becoming central to models of literary culture in the first two decades of the nineteenth century, before vernacular literary history had become a university subject. The phrase historical contrast is deliberately chosen for a similar breadth of reference. Periodization tends to evoke an academic and almost scholastic debate about boundariesare they real or only nominal?which may not have great significance. It is true that time is a continuum, and also true that it can be useful to divide a continuum. And perhaps literary periodization is now becoming nothing more than that sort of mathematical abstraction.

But periodization did not acquire institutional power in literary studies for reasons of mathematical convenience. What matters more than boundary-drawing is the broader premise that literatures power to cultivate readers depends on vividly particularizing and differentiating vanished eras, contrasting them implicitly against the present as well as against each other. Its a premise bound up with broader assumptions about literatures power to mediate historical change and transmute it into communityor in other words, with a model of literary culture. This book investigates the emergence of that model, and then asks what might replace it if (as I would argue) the authority of historical contrast has in recent decades been declining.

Most studies of this topic have been preoccupied with the significance of specific period concepts, rather than the significance of contrast as such. Much has been written, for instance, about the construction of Gothic alterity, or about the logic of uneven development that coordinates timelines in different parts of the world. I hope to preserve the central insights of those studies. For instance, it is important that European historicism has been shaped both by a peculiar relationship to classical antiquity, and by a colonialist impulse to map other regions of the world onto a European past. But on the whole, I will be less interested in particular period concepts or even systems of periodization than in the changing cultural functions of contrast itself.

Next page