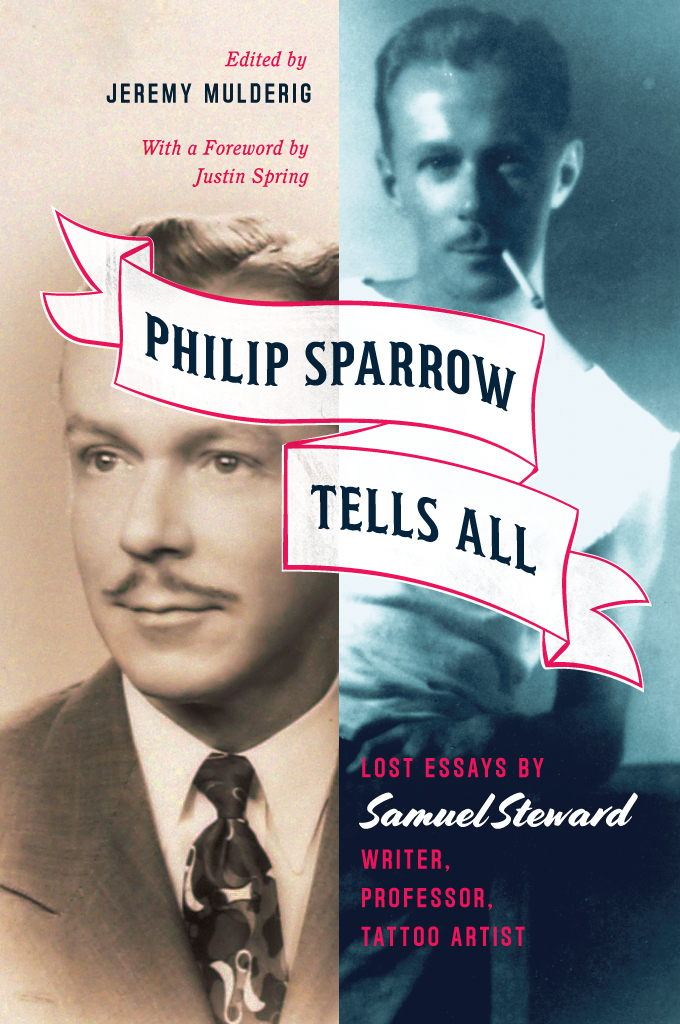

Philip Sparrow Tells All

Lost Essays by Samuel Steward, Writer, Professor, Tattoo Artist

Edited by Jeremy Mulderig

With a Foreword by Justin Spring

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

Samuel Steward taught at both Loyola University and DePaul University in Chicago and ran a famous tattoo parlor on the citys south side. His books include Dear Sammy: Letters from Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, Bad Boys and Tough Tattoos, and the Phil Andros series of erotic novels. Jeremy Mulderig is Vincent de Paul Associate Professor of English, Emeritus, at DePaul University in Chicago.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2015 by The University of Chicago

Foreword 2015 by Justin Spring

All rights reserved. Published 2015.

Printed in the United States of America

24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-30454-0 (cloth)

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-30468-7 (paper)

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-30471-7 (e-book)

DOI : 10.7208/chicago/9780226304717.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Steward, Samuel M., author.

[Works. Selections]

Philip Sparrow tells all : lost essays by Samuel Steward, writer, professor, tattoo artist / edited by Jeremy Mulderig ; with a foreword by Justin Spring.

pages ; cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Essays.

ISBN 978-0-226-30454-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-226-30468-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-226-30471-7 (ebook)

I. Mulderig, Jeremy, editor. II. Spring, Justin, 1962 writer of foreword. III. Title.

PS 3537. T 479 A 6 2015

814'.54dc23

2015019943

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z 39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

To Effie and Nell,

who made all things possible

Contents

I wish I could have included more of these essays in my 2010 biography, Secret Historian: The Life and Times of Samuel Steward, Professor, Tattoo Artist, and Sexual Renegade. They chronicle a substantial period in Stewards development, both as a writer and as a human being, andjust as importantly to a biographera period when he was writing little else.

The pieces were written during the 1940s, as Steward was passing through the most alcoholic period of his life. He seems to have undertaken them primarily in an effort to continue to write and publish. (Stewards really charming first novel, Angels on the Bough, had been published to fine reviews in 1936; as a younger man, he had also published a slim volume of poems; since then, there had only been several unpublished and unpublishable novels.) But these essays were also erotically inspired: composed as a favor to his dentist, Dr. William P. Schoen, who bore a striking resemblance to the actor Gregory Peck and who was looking for content to enhance the obscure professional journal he edited for the Illinois State Dental Society. Steward was infatuated with Schoen and called him Dr. Prettya play on words, for schn is German for the same. Thornton Wilder, one of Stewards many sex partners during the 1940s, had urged Steward to write essays and articles for magazines as a way of keeping himself engaged as a writer. But far from the New York magazine-publishing world, and never too sure of his talents, Steward didnt even approach the great popular magazines of the era, settling instead upon a little journal for Illinois dentists run by a man he wanted very much to seduce.

The essays are based in personal experience: reflecting, for example, upon how, during the war, Steward had briefly joined the navy, only to be ejected for food allergies; how he had taught cryptography to undergraduates as part of the war effort; how he had worked as a super at the Lyric Opera House; how he had adored Gertrude Stein; and even how he had come to loathe teaching. Steward had many personal ups and downs during the period he was writing these essays: having quit his teaching position at Loyola, he was unemployed and broke for a while. He disgraced himself among his friends with bad behavior brought on by heavy drinkingand one senses some of his anger and emotional instability in these essays, most notably the last of them. His private life during these years was similarly unstable: he was having sex in bathhouses, collecting dirty limericks and other graffiti, writing amateur pornography, hiring hustlers, picking up sailors in bars, and sometimes being beaten up or robbed by his tricksexperiences he came to savor even as they humiliated him. For several years he worked at rewriting the World Book Encyclopedia; and when the World Book gig came to an end, he took a make-ends-meet job in the book shop at Marshall Fields department store. Eventually, and after a good deal of drifting and soul-searching and worrying about poverty, he found his way back into teaching, this time at DePaul University.

As Stewards biographer, I found the years 194449 a near-blank so far as his archives and papers are concerned. Apart from the Illinois Dental Journal essays, I had only his amateur pornography (the Toilet Correspondence, now housed in the Kinsey archive), a little book of dirty limericks, a collection of toilet graffiti, a few important letters, and his own later recollections of those years, as he had written them up into several memoirs, only one of which was ever published. And yet these were the years during which Stewards youthful hopes of literary celebrity and academic security came to an end. So too did his two most significant literary friendships, with Gertrude Stein (by her death) and Thornton Wilder (by mutual agreement). As a result, the Illinois Dental Journal articles were of key importance in charting his transition to a new way of living and thinking. By the end of it, in 1950, Steward had joined Alcoholics Anonymous and got himself sober. He had met Alfred Kinsey. He was well along in his study of tattooing. And he had committed himself ever more deeply to sexual recordkeepinghis own, highly personal form of sex research. In doing so, he had begun keeping not only the Stud File card catalog, but the remarkable journalnow in the Kinsey librarythat would chronicle the next decade of his very active sex life, and, in a sense, replace the Illinois Dental Journal articles as the main testament of his everyday life experiences in Chicago, Paris, and San Francisco during the 1950s.

In my work as a biographer, I read Stewards Illinois Dental Journal essays with a mixture of emotions. I took great pleasure in reading them, of course. But who was this Philip Sparrow, so amusing and quirky and desperate to entertainand why, given his obvious wit, his fine prose style, his erudition and intelligence, was he publishing such finely crafted essays in a so hopelessly obscure magazine? Why should a writer of such talent throw his efforts away in such a manner? Along with pleasure, I felt pathos for this pseudonymous author, who in so many ways seems just this side of a lost soul.

How wonderful then to have this selection of the best of his Illinois Dental Journal essays rescued from oblivion. Beautifully edited and annotated, they have been selected and arranged for the reader in a way that shows off the evolving Samuel Steward of the 1940s to best possible advantage. I can only hope that in the years to come, more of Stewards fine, lost writingsfrom his impassioned essays for Der Kreis to his whimsical pornography as Phil Androswill similarly find their way back into print.