Contents

Guide

To Rebecca, with love and gratitude

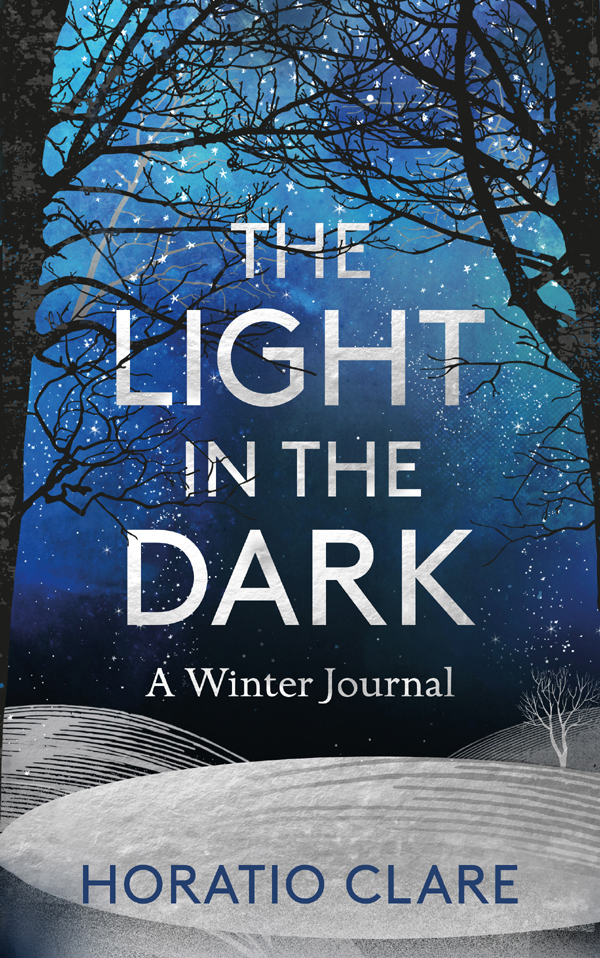

PROLOGUE: SUMMERS END

The last days of August were beautiful and the nights ethereal, glowing long after sunset. In Wales, on a glittering morning of dew and high whisks of cloud, the sun hot, Mum and I walked in the meadow by the stream, Apollo running circles and barking as if he were still young.

The Russian proverb goes, Life is not a walk across an open field, I said. But it is sometimes.

My mother, hugely smiling, repeated, It is sometimes!

We looked at the hill, our mountain, rearing over the valley. The bracken is on the turn, she said. Pale ribs like shadows ran under the green ridges.

We agreed we loved this change of season. The swifts went weeks ago. I saw them on an afternoon that was steamy with rain, hunting over the valley, twenty, thirty, and I knew they were going. Swifts come and go like spells. I watched them keenly, lucky to witness them just before they went. It is not the same with swallows: all over Europe and Eurasia watchers look up one day, or pause in thought, and realise that the swallows have gone. We all know what it means.

It is early September now, back in West Yorkshire, where I live with Rebecca and the boys (our son Aubrey, five, and Robin, his brother, sixteen), and I am looking for the swallows. I have seen them go as late as October in Wales, but here in the North of England I have never marked the moment. Two days ago I thought they must have gone; Rebecca has seen none either. Then yesterday, coming back from the seaside the coast of Lancashire, a-dive with kites and aglow with sunburn I saw some from the train, two or three over a stubble field, and cheered.

The train was old and packed. We could have been in Bulgaria, with the heat and the flushed faces and the children crammed between us; but at any time and in any country it was unmistakably one of the last trains on the last weekend of the summer.

This week the schools go back and the new year, the working year, begins. September is easy to love. I feel alive in the weather, in the light and the colour. Aubrey and I looked at the leaves this morning. On the Buttress, the wooded hump of hill which fills the view from this little house, the solid green is gone. Now there are many greens, all of them riching or fading.

Soon they will be yellow and red and orange and brown and gold, I said. And then the leaves will fall.

The first blew off the trees last weekend. If it were followed by spring or summer, I would love autumn unreservedly. Even the absence of the swallows and swifts and martins would be fine: they will come back, and they must go if the world is still to turn. But for all its gilding, I shrink slightly at autumn, as if I too lose leaves and thin, because I have come to fear winter.

Now it is after midnight on September 5th, my birthday. There are tiny black midges biting me in the attic; they are doing very well still and it is too muggy to keep the windows closed. It was a day as hot as July, yellowing greens like moulding broccoli and vapour greys, a wonderful thick, warm atmosphere, and I am thinking about winter. I loved the winter, with its miracles and Christmas colours, for years. Through school, through university, through first jobs, proper jobs, through years abroad and in Britain again, I relished it as I did all the seasons. Only in the last three or four years, here in the North, have I begun to admit that winter is tough. There is the weather: the black rains make you feel you are living in a tunnel under the sea, the roof leaking downpours; there is the enclosure of the moors, turning you in on yourself, shrinking the scale of life to a few small rooms, the dank and the dirty trains. There is the absence of light and the feeling of living in an ugly country, streaming roofs, weeping windows, dank inside and out. All over the North we experience these sensations which gather and spread like damp. In Wales the skies set in, crows-on-posts weather my mother calls it. Commuting in London is weeks, months, of grease-water running down the steps of tube stations, and buses like Louis MacNeices Charon:

... at each request

Stop there was a crowd of aggressively vacant

Faces, we just jogged on...

Last winter I thought I would go mad with depression. I was mad, but aware-mad, at least. Sometimes I hung out of my attic window, staring at the Buttress and the sky at the end of the valley with incredulity, waiting for the awareness to go and leave me raving.

It was nothing inexplicable: depression brings fear, entrapment, fault and failure wherever you look. The book I was writing seemed awful and I could see no hope: if I cannot write, I cannot support my family, cannot be the father my son deserves so the narrative goes. It is not fair to blame the winter, but it does set the stage so well, with its clamped-down rains, its settled and introverted darkness, its mean ration of light, its repetitions.

But this year will be different, it must be different. This book is to be a torch raised against it. I will take it down in notes and diaries. I will embrace this winter like a summer. I will try to see this little shard of the North as I would an unknown country. I will pay attention. Depression kills your power of vision, turning you fatally towards yourself, but I will practise looking and looking outwards like an exercise, as though I am training for an expedition. Mountains make sense in any weather. The voices of a wood always speak consolation: the trick is to resist the psychological deafness, that bung of jeering voices clogging the inner ear. Beware that glaze which creeps over the inner eye, blinding you to the brightness of moss in rain. I will not lose touch with nature. This is vital. I believe in immanence, in the oneness of living things. Maintaining that faith will carry you through the hardest times. Or such is the hope, this midnight. I start my birthday with many wishes, and this is one.

16 OCTOBER

Last week I saw two swallows, halfway down Wales, fine-tailed birds flicking against the wind, hunting. Late-breeding adults, they will have raised two broods. On their way now and travelling, they will not really stop anywhere long. In a month or so from now they will be around the Congo and Cameroon, twinning the world, linking every raised head and every eye that sees them. Today was astounding, courtesy of ex-Hurricane Ophelia. There was a pink Chinese silk balloon sun in a mustard sky. It looked like a portent, if not the apocalypse. And I saw a hobby! They should be gone, but she seemed large and fit, slicing over the town. If you can catch swifts in level flight you can catch anything, and there was plenty around. A sparrowhawk was up there too; it mock-attacked a pigeon which burst out of its tree in a fluster. All the birds seemed to be up, riding the currents. Later the sky cleared; there was sun and tremendous wind in a blue rush over the moors. It was a pale-white whirl of light over the plain towards Manchester and Liverpool and Wales. I turned my face to hot sun-wind (we had sun-rain a few days ago, when it seemed to be raining light) and watched jackdaws in storms over the high woods, rolling in black sparks on the breakers of the sky.

I take down these moments in the middle of driving, commuting or ferrying the family, consciously sealing them into the visual memory. Look hard! Take a picture with your mind, I say to Aubrey as we practise his letters. It works.