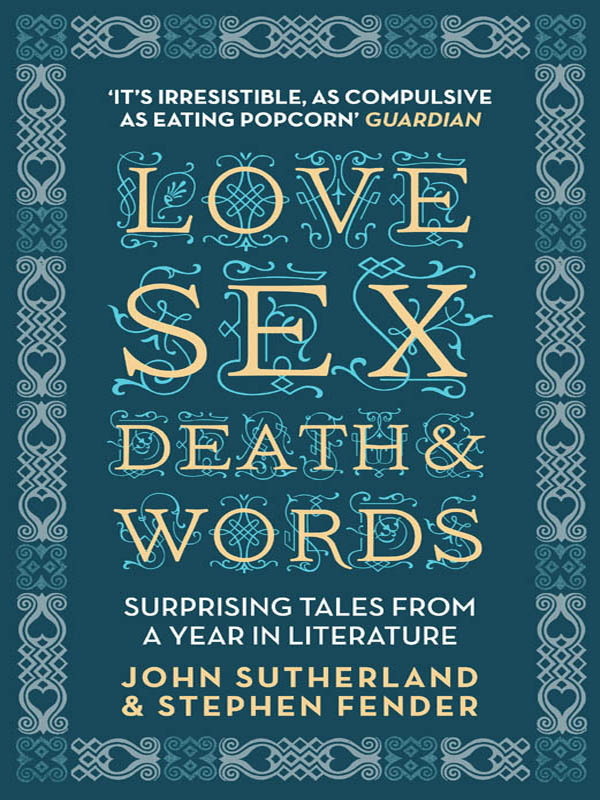

SURPRISING TALES FROM

A YEAR IN LITERATURE

JOHN SUTHERLAND & STEPHEN FENDER

Previously published in the UK in 2010

by Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

3941 North Road, London N7 9DP

www.iconbooks.co.uk

This electronic edition published in the UK in 2011 by Icon Books Ltd

ISBN: 978-1-84831-269-2 (ePub format)

ISBN: 978-1-84831-270-8 (Adobe ebook format)

Printed edition (ISBN 978-184831-247-0)

sold in the UK, Europe, South Africa and Asia

by Faber & Faber Ltd, Bloomsbury House,

7477 Great Russell Street, London WC1B 3DA or their agents

Printed edition distributed in the UK, Europe, South Africa and Asia

by TBS Ltd, TBS Distribution Centre, Colchester Road,

Frating Green, Colchester CO7 7DW

Printed edition published in Australia in 2010 by Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd,

PO Box 8500, 83 Alexander Street,

Crows Nest, NSW 2065

Printed edition published in the USA in 2011 by Totem Books

Inquiries to: Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

3941 North Road, London N7 9DP, UK

Printed edition distributed to the trade in the USA

by Consortium Book Sales & Distribution

The Keg House, 34 Thirteenth Avenue NE, Suite 101

Minneapolis, Minnesota 55413-1007

Printed edition published in Canada by Penguin Books Canada,

90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700,

Toronto, Ontario M4P 2YE

Text copyright 2010 John Sutherland and Stephen Fender

The authors have asserted their moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Typeset by Marie Doherty

Contents

6 April: Francis Petrarch catches his first sight of Laura, and will go on to write 366 sonnets about his love for her

30 April: The United States buys the entire Middle West from the French for $15 million, more than doubling the size of the country. Fenimore Cooper has his doubts

24 May: Guy Burgess tries to telephone W.H. Auden just before defecting to Moscow

16 June: James Joyce goes out on his first date with his future wife, Norah Barnacle

5 July: Rebecca Butterworth writes to her father from The Back Woods of America asking him to pay her way back to England

27 July: President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signs the Federal Writers Project into law

17 August: Charlotte Perkins Gilman commits suicide

12 September: Death of a literary louse

6 October: William Goldings sour-tasting Nobel Prize

27 October: Maxine Ting Ting Hong is born in Stockton, California

17 November: Sir Walter Raleigh goes on trial for treason

10 December: Mikhail Sholokhov collects his Nobel Prize for Literature in Stockholm: how an apparatchik became an unperson

About the authors

John Sutherland is Lord Northcliffe Professor Emeritus at University College London. He has taught at Edinburgh University, UCL, and the California Institute of Technology. He has two honorary doctorates (Surrey and Leicester Universities) for services to literary criticism. A Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, he is also President of the Society of Indexers, and was Chair of the Man-Booker Prize panel, 2005.

Stephen Fender was born in San Francisco, and educated at Stanford and the Universities of Wales and Manchester. He has taught English and American literature at the University of Edinburgh, University College London and Sussex University, where he was Professor of American Studies from 1985 to 2001, and founding Director of the Graduate Research Centre in the Humanities. He has also taught in the USA at Santa Clara, Williams and Dartmouth Colleges, and while at UCL he designed and taught MA-level courses at the Institute for US Studies, London. At present he is an Honorary Professor of English at UCL.

Acknowledgements

Stephen Fender would like to thank Winifred Campbell, Brian Oatley, Peter Nicholls, Janet Pressley, Anna Ranson, and Jennifer Wall for their ideas and comments.

Preface

2 July

2010 On this day, as the authors of this book put their heads together to write their preface (traditionally the last thing to be written), Beryl Bainbridge died. She was well on in years and was known to be frail. The obituaries were all in stock and up to date. They appeared, some of them, the same day virtually before the novelists body had cooled.

Bainbridge was much loved one of the national teddy-bear authors, along with her NW1 neighbour, Alan Bennett. The other image that attached to her was that of perpetual bridesmaid. She was forever being shortlisted, or touted, for the Booker Prize, the UKs major award in fiction, but never quite won it. The British love a good loser, and none was a more gracious loser than Beryl.

The anecdotes about her were, many of them, chestnuts, but still relished because she was so liked. She was expelled from school at fourteen as a corrupting influence, having lost her virginity to a German POW called Franz the year before. Her subsequent life, which included a walk-on part in Coronation Street, was rackety. As the Guardian obituarist, Janet Watts, records:

One day her elderly former mother-in-law appeared at the front door, took a loaded gun from her handbag and fired. Beryl foiled that attack, and the episode appears in The Bottle Factory Outing, which won the Guardian fiction prize.

One of us John Sutherland also lives in Camden, where Bainbridge, now a dame, used to take a shortcut in front of where he lives. Her lungs were ruined by years of smoking and she would often take a minute or twos wheezing rest on a doorstep with a street drunk called Tom, with whom, she said, she discussed such things as W.B. Yeatss late poetry.

It was a remarkable life. But prepared as the world was for it no one knew precisely when it would end. Her death was a wholly random event. She herself confidently expected to die in her 71st year (the age her mother and grandmother passed away) and made a touching TV programme, Beryls Last Year, a kind of Ignatian meditation on her own end. She was, as it happened, wrong surviving, as she did, three more years.

Life (and death) are unless you are facing execution like Gary Gilmore (see our entry for )?

For our convenience we package literature into syllabuses, curricula, canons, genres, Dewey Decimal Sectors. But literature is vast, growing (ever faster) and inherently miscellaneous. This book, using a calendrical frame, is a tribute to that miscellaneity. Anything can happen anywhere anytime. As can nothing, as Philip Larkin sagely reminds us.

The authors have between them a hundred years of scholarship, teaching and conversing about literature (often between themselves). What they know is like two crammed attics full of interesting junk. But that junk is worth having. The world of books, they believe, is something forever to be explored, never comprehensively mapped. As you read this book, diurnal entry by diurnal entry, stop and try to predict (without peeking) what is going to happen on the next day. Chances are you wont be anywhere close.

Next page