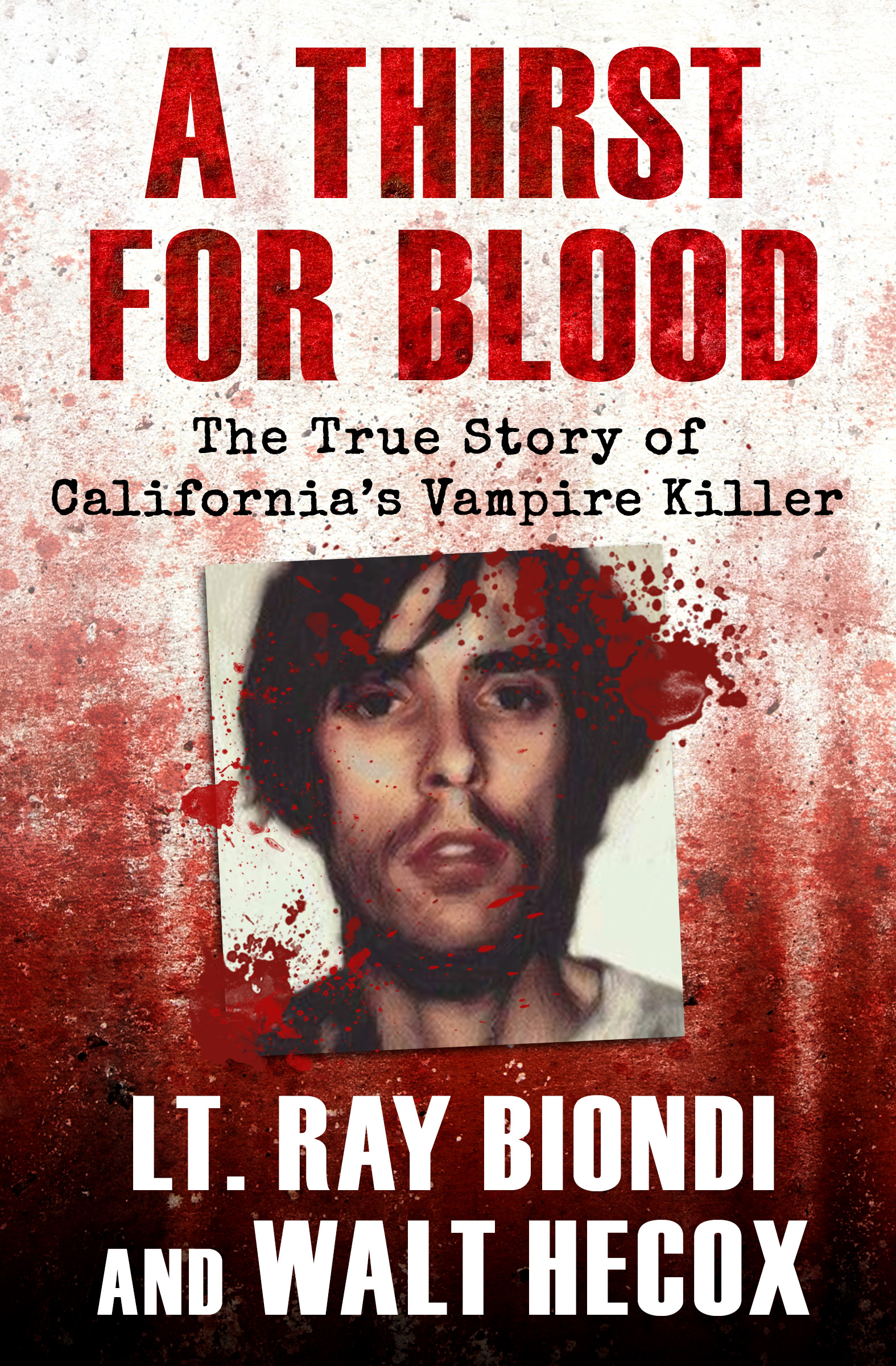

A Thirst for Blood

The True Story of Californias Vampire Killer

Lt. Ray Biondi and Walt Hecox

December 29, 1977

When the phone rang at 9 P.M. I groaned. I didnt want to answer it, but I did. On the second ring.

Biondi, Homicide, I said, forgetting for a moment that I was home.

I was then an inspector, with fifteen years under my belt, and had been chief of Homicide for the Sacramento County Sheriffs Department for less than two years.

Despite the time off I had just spent with my family over Christmas, I was bushed.

Maybe, Id reflected earlier in the day, I was dragging tail because of my days off. My wife Carol and I had five boys ranging from five to fourteen years of age, and they were experts in keeping Mom and Dad on the run.

Sacramento County was closing out 1977 with a bang, and that was the right word for it. Unfortunately, it wasnt going to get better anytime soon. Too many people in my jurisdiction were having their lives end unnaturally, with deliberateness and enthusiasm. Our citizens, it seemed, were dying around us at an alarming rate.

On the phone was the duty dispatcher, who was in constant touch by radio with our units patrolling the approximately nine hundred square miles of unincorporated area that encircled the state capital. She reported, in the emotionless, monotone delivery of police dispatchers everywhere, a shooting at 3734 Robertson Avenue. Though not yet a homicide, it sounded as if it had the makings of one.

Hanging up, I quickly decided to assign the case to Sergeant Don Habecker and Detective Fred Homen, and I made the appropriate phone calls.

Habecker had been in Homicide a year or so longer than I had, and he had become my right hand. Quiet, low-key, unflappable under fire, he could be counted on to supervise the investigation at the crime scene. A family man, he had all boys, toothree of themand we were always trading stories about our sons latest rounds of mischief.

Homen, a trim statue of a man with curly dark hair, exuded genuine congeniality from every pore and had the well-deserved moniker of Friendly Fred. Not surprisingly, he was the consummate organizer of law enforcement social functions. But in house he had another nickname. Time and again, when any of us walked away from our disheveled desks in Homicide for any length of time, we would return to a newly organized desktopirrefutable proof that Mr. Clean had struck again. Homen, characteristically, had made an art out of the careful collection and labeling of evidentiary minutiae at the scene, always the first step toward finding the perpetrator.

When the two detectives arrived at the modest tract house on the east side of town they directed patrol units to seal off the area to keep the curious at bay.

Then Habecker and Homen went to work.

When Habecker arrived at the hospital later that night he was told that Ambrose Griffin had just expired in the emergency room.

The ambulance had been followed to the hospital by the victims wife and two sons, and their wives. They were now in a room at the hospital with a Catholic priest, Habecker was told by a family friend. Would it be all right if he waited until tomorrow to question them?

Habecker didnt push. The grieving family deserved privacy. Of course, had he any reason to suspect a relative, Habecker wouldnt have been so thoughtful. But from all indications and reports at the scene, the killing appeared to be what we in the business call a drive-by.

He spoke to Carol Griffin and her sons the next morning in the living room at the house on Robertson Avenue. The more she thought about it, she did remember having heard two popping noises, she told Habecker. They hadnt meant anything at the time. What had concerned her greatly and occupied all of her attention at that moment had been the frightful sound of her husband yelling.

He stopped almost as soon as he started, she explained, pushing a wadded tissue to the corner of one reddened eye. Then he turned toward where she was standing in the doorway of their home and, with no further sound, crumpled to the ground.

Carol Griffin remembered screaming and running toward her husband. As she did she shouted over her shoulder to their two sons, who were in the house. Call for help! Your father had a heart attack! She noticed the trunk of the car was still open. The thought crossed her mind that her husband must not have reached the car before the attack struck him down. When they had arrived home from their shopping trip and parked in the driveway a few moments earlier, he had handed her the keys and asked her to open the trunk. She had done so and had taken a sack of potatoes into the house with her. Ambrose had followed with two sacks of groceries. He was returning for the last two bags in the trunk when it happened.

Habecker knew, from interviewing witnesses at the scene, that Carol Griffin had knelt beside her stricken husband, sobbing to neighbors about his being just the right age for a heart attack.

Not until the fire department paramedics arrived did she learned that a heart attack had nothing to do with her husbands condition.

As soon as I was briefed on the details I worried that the shooting on Robertson Avenuein what was referred to as Sacramentos East Areawas going to be a tough one to solve. Most murders, senseless as they may be, do have some sort of pattern and visible motive, whether its robbery, anger, or jealousy. So far, this one lacked such order.

Ambrose Griffin, an engineer for the Federal Bureau of Land Management in Sacramento, was fifty-one years old. According to his family, he was an even-tempered man with no known enemies. Later, Griffins fellow employees in the office where he worked agreed. He was a upper-middle-class civil servant who had, like thousands of others, settled in one of the sprawling tree-studded subdivisions that had sprouted after World War II in the suburbs of Sacramento. He and Carol had raised a family there and planned to stay at least until they reached retirement age. They loved the home on the oversized lot that backed onto a meandering creek bed.

The picture we were getting of our victim would have placed him comfortably on a Norman Rockwell magazine cover. His was a loving, supportive family that gathered at the Griffin home for holidays. He was Mr. Regular Guy whose clothes stamped him Middle America, from the white T-shirts to the sleeveless sweater from Wards to the Pendleton-plaid shirts he wore on evenings at home.

But someone had shot him down as he walked, supremely confident of his safetyas well he should have beenfrom his house to his parked car. My God, he was killed in his own yard!

Soon the two Griffin sons produced what they hoped would be a clue to their fathers death. Bob Griffin, the younger son of the murdered man, called Homicide to say that his brother Rick had seen a man carrying a rifle near the Griffin home. They were outraged and angry when they spotted the man with the gun so soon after their father was shot. They followed the man to a house on a nearby street, then called us.

We went out and talked to the man. His rifle, a 30/30-caliber hunting rifle, was not our murder weapon. Ambrose Griffin had been shot with a smaller .22-caliber weapon. In addition, the man had an alibi: He had been working at a gas station when the shooting on Robertson Avenue occurred. He was not our man.

As we always do, whenever we are able to after a homicide, we packed a lot of work into the next twenty-four sleepless hours. Sheriffs deputies or detectives talked to everyone residing within two blocks of the shooting scene. Then the questioning spread to adjoining streets.