Early January. The year feels as pristine as the first page of a childsexercise book. Weve still in a holiday mood. Maybe well go to a movie,drop in on friends, invite someone over but lets stay home tonight,says Peter, just the three of us. So we do, and after our nine-year-old daughter Kate is tucked in bed, we talk, not about how longthe winter will last but about the year, indeed the years, ahead.Somehow that first page on the calendar always creates a feeling ofhope,of being on the brink, of making change. How could we haveknown at the time that what will emerge from this evening will beyears ofroamingand discoveries, culminating in a single moment?

I t stood at the periphery of the village on a calm little side street, an impasse in French. At its end the street made a dog-leg turn into a yard, which meant wed be exposed to minimal traffic beyond the egg-yolk yellow poste van. The blue-and -white sign at the corner read Impassedelglise: wed be close enough to the church that we could rely on its bells to tell us the time. A stable in its previous incarnation and still a work-in -progress, the house was one in a row of small modest cottages. Framed by the living room window, a west-facing garden overlooked nothing but lawns, cherry trees, the side of an old barn and the green mounds of hills in the far distance; the view was even better from the balcony upstairs off the main bedroom. The stone wall in the salon had already been uncovered, and for the mantel there was a length of oak, found in a former shed, that was so ancient you could pass your hand along it and feel the faint indentations where generations of horses had rubbed it with their chins. Outdoors there would be a terrace and a built-in fireplace to grill merguez (spicy lamb sausages) and magretsdecanard (duck breasts), with space to plant thyme and rosemary right next to it.

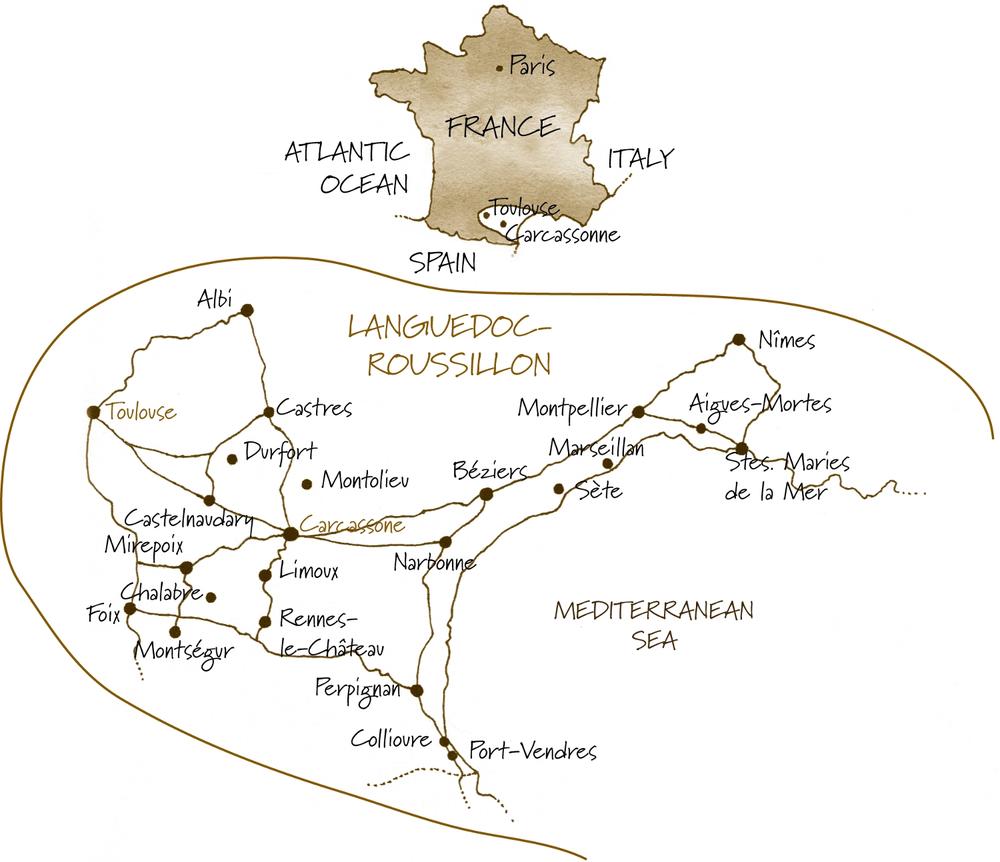

Wed been coming to the Languedoc for eight years by then, loving the region more with each visit. Even if we did not yet have a French house of our own (the search for one, if never full-time, was ongoing), we were already putting down roots of a minor kind: buying an elderly, diesel-fuelled war-horse to save on car rental costs and parking it in a barn when we went away; signing up for a cartedefidlit at the local Champion supermarket; and, this time, leaving two boxes behind in our friend Nigels attic. Inside them were four yellow-checked napkins, a towel, a cake of lavender soap, salt from the Camargue, coarse-grained mustard, wine vinegar, three bottles of local Fitou wine and a bottle of pastis still half full: we viewed them as a start, a commitment, tangible evidence that we would be back. One afternoon towards the end of our stay we were sitting outside in the sun, looking across at the great surging shape of the mountain of Montsgur, having a cup of tea with Nigel who wakes up to this view every morning and telling him about our latest house-hunting failures. Too large, too close to the trucks thundering by, a roof that sagged like an old mattress. A pleasant enough cottage but the village had no boulangerie, a serious lack if your daydreams include pre-breakfast saunters down the street for fresh croissants.

Why dont you check out the house that belongs to ___?, and Nigel named a couple we had met on a previous visit. Its small, he said. That was fine. Its in ___, and he mentioned a village we not only knew and liked but had actually stayed in some years earlier. Theyre renovating, he said (better and better), and I think they might want to sell. So we went and looked.

To be blunt, it was a mess, as house renovations invariably are. Standing there amid the clutter and the stacks of lumber, we tried to imagine the finished structure as the owners explained their intention to use materials and architectural details salvaged from this house and others; rcuprer is the French word. We saw additions when we dropped in a few days later, a turn-of-the-century glass-panelled door with Gothic arches, an old beam exposed over the kitchen window, the wide-planked floor upstairs. En route to Toulouse the day before we headed back to North America, we paid one last visit to a place we already felt at home in.

But wont it be too small? said Peter, somewhere over the Rockies.

At around five metres wide and perhaps twice that in length, it was inarguably a compact house but, going over the plans with the owners, I had come to admire how well every square centimetre would be utilized. I reminded him of the spacious pantry, the little cupboard just the right size for bottles of gas for the stove. And theres all that space under the stairs. In England, I continued, exaggerating only slightly, people often convert that space into a second bathroom.

Ill need a studio to paint in.

How about the front room upstairs?

What about when people come to stay?

We could section off half the space with folding doors. That way, theyd have a view of the chteau.

Its turret and battlements, glimpsed across the treetops of a neighbours garden, were just one more draw.

Were interested, we wrote in a letter to France some days later. Phone calls followed, and photos and floor plans with measurements, so that, even from far away, we could start planning where to position paintings and bookshelves. And, most important of all, the dining table.

In the end, it was as simple as that.

What we couldnt have realized during that first visit to the chaotic building site was how ideally the house was positioned. How the morning light would filter through the lace curtains in the kitchen, casting muzzy wavering shadows on the tiled floor, and how, by early afternoon, the earth would tilt enough to send sunlight flooding in through the living room window (exceptionally large for a French cottage, it had once been the vitrine of a shop).

We knew the provenance of just about everything in the house. That was the bonus of buying a place that was still in the works and not yet complete when we returned to France almost a year later to finalize the formalities. Realizing that more hands would help us to move in sooner, we rolled up our sleeves and joined a crew that seemed to change daily; at least thirty people contributed to the labour of love. Philippe, the master carpenter who built the kitchen cupboards, was a man so enamoured of wood that he once came out into the garden where we were planting herbs bearing a handful of fresh curly shavings, just so we could share his pleasure in their resinous tang. In between sharing recipes Bernard, another carpenter, never tired of telling us why he had left his job in a Manhattan restaurant to return to his native France.