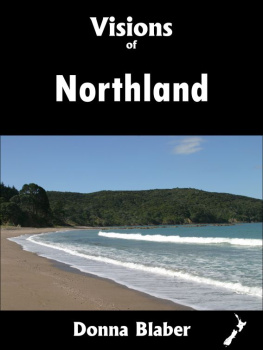

Dedicated to Felix and Carlo, on a Northland beach, and in memory of Ralph, not too far north of there

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION THE DINGHY AND THE DRY LAND

The authors dinghy, photograph by Bruce Foster

I

I keep a dinghy on or beside the front lawn of my home in the ridgetop Wellington suburb of Hataitai. Each morning, when I pull back the blinds, the second or third thing my eyes fix upon is the upside-down dinghy. This is how it goes: The sun on its way up; the four cabbage trees; sometimes a t. And the dinghy. In that order. When pressed on the matter, I tell friends that in this age of global warming and rising seas, keeping a dinghy on a suburban lawn, some 50 metres above sea level and kilometres from the nearest coastline, isnt an outlandish idea. The aquatic world has always been volatile and unstable, and sea level has never been something you can count on a fact underlined by the recent discovery of a whale skeleton at an archaeological site atop the Miramar Peninsula, only a few kilometres from where I live, and an impressive 45 metres above sea level.

In a 2015 lecture at Victoria University of Wellington, Bruce McFadgen posed the question: How could such a huge creature have ended up on this hilltop? The scientific consensus, he proffered, was that the humpback had been lifted from Cook Strait while still alive and posited atop the ridge by a massive tsunami. This would have occurred during a period of great seismic unrest. A few hundred years back, most likely. Other findings in the surrounding terrain support such a theory and time frame.

Each spring, laid flat beside our front path and blanketed in clematis, the dinghy erupts into vibrant, seasonal life. Warmed by the sun, the aluminium hull generates an agreeable microclimate. Plants accumulate snugly around it. During winter, the encompassing vegetation is reduced to an entanglement of vines, beneath which the boat glimmers, dimly a scale model of an abandoned, overgrown Eastern European steelworks. Since my brother Brendan and I bought the dinghy in 1974, it has served a variety of functions, not all of them practical. It featured alongside Motukorea (Browns Island) and the artist Christo in my short story, Belly of Jonah, which Robin Dudding published in his literary journal Islands in 1987. Two years previously, a drawing of it appeared on the cover of that same archipelagically titled journal. The vessel, reconfigured in wood, then resurfaced in a suite of illustrations by Noel McKenna for my poem Great Lake, published in a hand-printed edition from Niagara Galleries, Melbourne in 1999:

Now he is rowing

a dinghy across this calmness which is the

exploding of calmness. Clinker-built fifty years ago, the dinghy was restored by a local Mori carver his weekends devoted to boats to

the smell of varnish and trees, its perfection

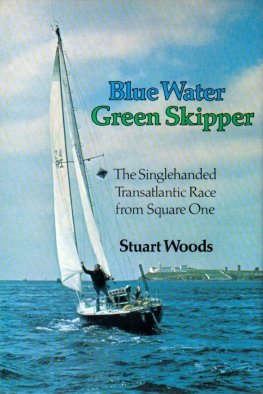

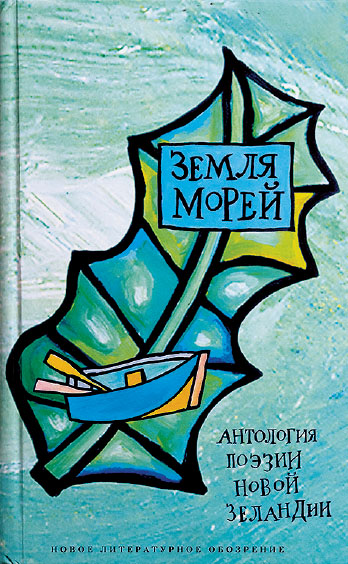

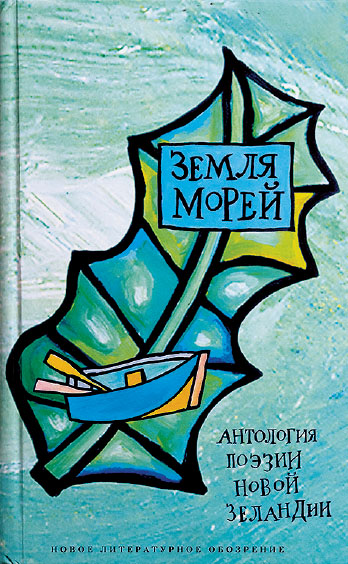

Land of Seas: Anthology of New Zealand Poetry, translated into Russian, ed. Mark Williams and Evgeny Pavlov, cover design by Mark Harfield, with drawings by Gregory OBrien

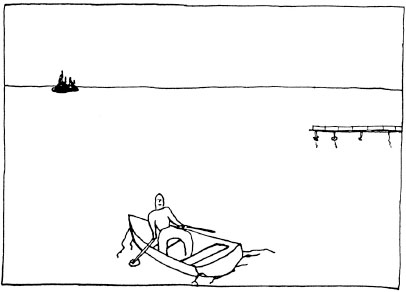

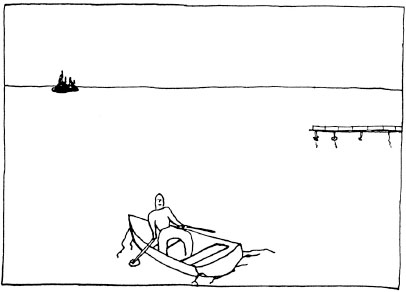

Noel McKenna, illustration for Great Lake, ink on paper, 1999

Euan Macleod, Rowing Rudd Island, 2009, oil on canvas, private collection, Sydney

When I was asked, in 2005, to design a cover for an anthology of New Zealand poetry translated into Russian, Land of Seas, the dinghy with oars became the cover motif. More recently, while writing a monograph about the Sydney-based, New Zealand-born painter Euan Macleod, my self-image as both captain and crew of such a vessel gained another dimension. In the course of that project, I was co-opted as a model, shirtless and holding on to the transom, while Euan worked on Rowing Rudd Island (2009). The painting was not a radical departure for Euan, as a dinghy almost identical to mine had been a presence in his art for many years before I clambered aboard. In his mind, the dinghy had established itself as a symbol of his late father, an amateur boat-builder who constructed a considerable yacht in the living room of their family home, rendering the space unusable for much of the artists childhood. Euan remembers standing, aged nine, on the front lawn one Saturday morning as the windows at the front of the family home were removed and his fathers magnum opus was hauled forth into the outside world.

Whatever the personal resonances, the recurrent dinghy in Euans paintings is alive with broader possibilities as a symbol of both exile and homecoming, confinement and liberation, death and life; it can be the Ship of State or its close relation, the Ship of Fools. With its keel and skeletal framing, it is a human torso with spine and ribcage, or the interior of a church or a place of habitation. It could as easily be a lifeboat as it could be D. H. Lawrences Ship of Death.

When Euans father died in 1994, he was laid out in the living room of the family home where the yacht-in-construction had once been installed. In subsequent paintings of his dead father in this darkened space, the coffin has become a sailing dinghy or punt for crossing the River Styx. Sleep! In your boat brought into the living-room. The lines of John Berryman (from Love and Fame) could never have found a more apposite illustration, supreme admirer of the ancient sea.

In a similar fashion, shortly after his death in 2004, painter Pat Hanly lay in an open coffin in front of the altar at St Matthew-in-the-City, central Auckland. An avid sailor, Pat had a reputation for donning his life-jacket before leaving his suburban home in Mount Eden and wearing it as he drove across the city to the bay where his yacht was moored. In the coffin, the legendary life-jacket was fastened tightly around his chest, while a large protest banner from the 1980s NO NUCLEAR SHIPS hung above him.

The last email I received from historian Michael King, only a few days before his death in late March 2004, contained an attachment detailing a range of nautical vessels which were being deaccessioned from a local museum. Without offering any real explanation, Michael had it in his head that I might have some use for one of these. I wondered at the time but even more so later if this was a cryptic message. Was he suggesting some kind of voyage? A few years earlier, shortly before my family and I were to travel to Menton in France, Michael summoned Jen and me to the Deluxe Caf in downtown Wellington, to show us his photographs of a clearly memorable sailing excursion on the Mediterranean during his time as Mansfield Fellow. Perhaps he was assuming I was a more serious boatsman than is in fact the case a conclusion he could, I guess, have drawn from the nautically inclined titles of many of my books:

Next page