The Author hereby asserts his / her right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with Sections 77 to 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages.

Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders of the photographs in this book, but one or two were unreachable. We would be grateful if the photographers concerned would contact us.

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library.

For all your musical needs including instruments, sheet music and accessories, visit www.musicroom.com

For on-demand sheet music straight to your home printer, visit www.sheetmusicdirect.com

Introduction/Chapter Zero:

Visions of Madonna

On the 26th of July, 1999, in a club in Manhattan, Bob Dylan delivered one of his greatest performances ever of his well-loved 1966 epic Visions of Johanna. As if to acknowledge and signal his awareness of the power and freshness of this latest reinterpretation, the singer-bandleader effectively changed the title of the song halfway through, by starting to sing the chorus as: And these visions of Madonna are now all that remain/ have kept me up past the dawn.

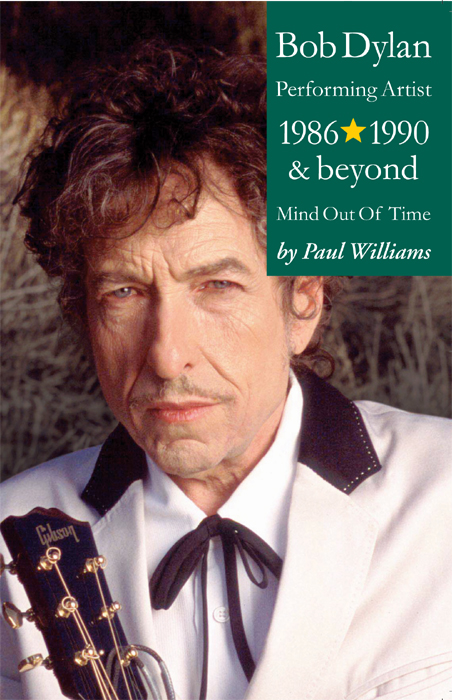

Where does genius come from? This book proposes to examine where the improbable 58-year-old artist singing in front of 900 people in Tramps that night came from, in the sense of what roads he had walked down, artistically and personally, in some of the preceding thirteen years of his life and work.

In 1997 a Newsweek writer reported that Bob Dylan had recently told him that ten years earlier (summer 87): Id kind of reached the end of the line. Whatever Id started out to do, it wasnt that. I was going to pack it in. Onstage, he couldnt do his old songs. You know, like how do I sing this? It just sounds funny. He goes into an all-too-convincing imitation of panic: I -I cant remember what it means, does it mean is it just a bunch of words? Maybe its like what all these people say, just a bunch of surrealistic nonsense.

Dylan told the magazine that he got help (during his 1987 nervous breakdown as a performer) from Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead: Hed say, Come on, man, you know, this is the way it goes, lets play it, it goes like this. And Id say, Man, hes right, you know? Hows he getting there and I cant get there? I had to go through a lot of red tape in my mind to get back there.

This book is called mind out of time, and argues that this is how Bob Dylan sees himself (what he aspires to be) as a songwriter and performer. So, although the general structure of this narrative will be chronological, I feel its appropriate to step outside of chronological sequence for the purpose of this introduction, and start the story by looking closely at one fine example of this artists ability to stop time and thereby encompass it and conquer it, in the timeless world of ephemeral art. Onstage in a particular club on a summer night in New York City.

This ephemeral performance art becomes accidental when it loses its ephemeral status because someone, not the artist, captures the musical performance on recording equipment so it can be heard outside of that room and that night, by people other than the fortunate few who were in the theater at the show. A book like this, by its nature, is not about the intentional art of the performer, which takes place at a particular time and place. This non-accidental art is only experienced by the people who are in the audience that day; and even being one of those people doesnt empower me or anyone to write about the experience, unless we have total emotional recall, because the simple act of taking notes creates a distraction for the observer and a distance between the listener and this remarkably alive art form.

So this book cannot meaningfully be an in-depth look at concerts I attended; it must be the report of a listener who has listened attentively to live recordings whose existence and availability is largely accidental, in terms of the artists control or intent.

Of course, I feel better qualified to write about these recordings thanks to the large number of Dylan concerts Ive experienced as an audience member over the course of 41 years (see Appendix II). And certainly it is no accident that Bob Dylan sings and plays his heart out in front of a live audience almost every third night of his life (from 1989 to 2003 he has played close to one hundred shows every year). He is a brilliant, conscious artist. But most of the body of work that this book and its companion volumes examine is accidental in its recorded form, which is the only form we can discuss together. The story of the live audience experience of these works of art is the story of hundreds of thousands of individuals in a vast array of mind-states at specific moments in their personal histories, some sitting or standing where they can see and hear well, others far in the back of a large auditorium. But accidentally, you and I can approach these works of art as though they were enduring communal objects, so that when I describe the mastery of the performing artist singing this particular piece on this particular night in 1999, you have the opportunity (if you search patiently) to listen to the same recording Im referring to.

Okay. Visions of Johanna (or, if you like, Visions of Madonna), was the fifth song Bob Dylan and his band performed on Monday July 26th, 1999, on 21st Street in Manhattan. Larry Campbell and Charlie Sexton on acoustic guitars, Tony Garnier on string bass, David Kemper on drums, and Bob Dylan on vocals and acoustic guitar. What makes this eight-minute performance so remarkable is its expressiveness, its artistry, its structure, its musicality, its freshness, its vision. You could start here (and many young appreciators of Dylans music have started with recent concert recordings). This is not a repeat of a work of art created back in 1966. It is unmistakably a great work of art created at the time of its performance. Something new and original and thrilling. Bob Dylan once said, He who is not busy being born is busy dying. His greatest accomplishment as an artist has been to stay true to this demanding dictum, in the face of the inevitable obstacles from within and without that all human beings and all artists must contend with. Our story in this volume begins at a particularly difficult moment in this process, August 1986 to July 1987. (Id kind of reached the end of the line.) Visions of Madonna and thousands of other performances that will be discussed herein are evidence that a committed artist can indeed use those painful years when he finds himself busy dying as opportunities and stimuli to learn new ways to get there, back to being busy being born. This song, this performance, on this night in 1999, is certainly about being born. As an artist, a singer, a musician. And as a lover and a human being. Listen to the way he sings, How can I explain? Its so