Table of Contents

ALSO BY ANTONINO DAMBROSIO

Books

Let Fury Have the Hour: The Punk Rock Politics of Joe Strummer

Democracy in Print: The Best of The Progressive Magazine, 1909-2009 (contributor)

Screenplays

No Free Lunch (featuring Lewis Black)

Let Fury Have the Hour: The Clashs Permanent Revolution

La Terra Promessa: In Sun and Shadow (Part I) and Diamanti nel di Massima (Part II)

For Franco DAmbrosio

Like a buddy fallen in battle, these guys made a difference, youre hearing the truth of a man, a soul, a heart.

Arlo Guthrie on Johnny Cash and Peter La Farge

Gaily the Troubadour / Touched his guitar.

Thomas Baynes Bayly

He who sings scares away his woes.

Cervantes

BEFORE

I Had to Fight Back

On a particularly gray, cold morning in Bowling Green, Ohio, back in February 2005, I found myself in a small, windowless room, where an undergraduate student from Bowling Green State University had just handed me a stack of records, CDs, books, and magazines. She also congratulated me on the talk I had given the night before. At the invitation of Daniel Boudreau, a Ph.D. candidate in the American Cultural Studies Department, Id come to Bowling Green on a lecture tour to support my first book, Let Fury Have the Hour: The Punk Rock Politics of Joe Strummer.

The university had graciously offered to grant me access to its prestigious Music Library and Sound Recordings Archives. I soon found myself in the third-floor office of the gregarious archivist Bill Schurk, who regaled me with stories about music and the things archivists find excitingwhich I happen to find exciting, too, including the documenting of materials that may seem worthless but over time provide an invaluable record of a moment that has slipped away but thankfully has been preserved forever.

For anyone who loves music, the Sound Recordings Archives is a magnificent placeevery recording in human history seems to be housed there. I was excited to get into the shelves of rare LPs, music books, and other music-related media. After speaking with Schurk and his staff, I felt like Tom Hankss character in the film Big when he was unleashed in FAO Schwarz and danced joyfully on the huge piano. I requested as many records as I could possibly listen to in my allotted time. The list was long and contained mostly recordings Id never heard of, including rare albums by Woody Guthrie, The Carter Family, Django Reinhardt, Spencer Davis, Charlie Parker, and The Clash.

After thanking the student who had given me the records, I handled each one as if it were a priceless artifact. (To me they actually all were priceless artifacts.) I listened intently to all of them. Then, near the bottom of the stack, I came upon a Johnny Cash record that Id checked off the list as an afterthought. I was happy, though, that the record was part of the archives; I had discovered this little-known Cash record while writing about Cashs collaboration with The Clashs former front man Joe Strummer for my previous book.

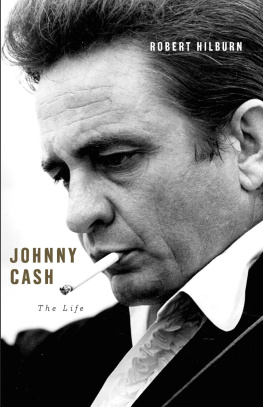

But now, as Cashs gaunt face and steely eyes stared back at me from the Bitter Tears album cover, I realized that there was something striking, even unsettling about this image. This wasnt the myth, the persona that has become Johnny Cash, but rather something truer, more authentically John R. Cash, the former sharecropper and cotton picker from Arkansas. In contrast to looking rock n roll hipa swaggering, pompadoured balladeer with an acoustic guitar slung over his shoulderhere his famous head of hair was cropped short and ringed by a red headband. The look in his eyes seemed troubled, as if what he was about to share was something heavy and hard.

I slid the record out of its sleeve and a piece of paper fell out, landing at my feet. Picking it up, I saw that it was a copy of a letter Cash had penned on his own letterhead, with his cursive signature at the top, and the proclamation

NOBODY BUT NOBODY MORE ORIGINAL THAN JOHNNY CASH

at the bottom. One line jumped out at me: D.J.sstation managersowners... where are your guts?

The disc in my hand was not the original pressing. Bear Family Records, a German independent record label, reissued it in 1984 with lyrics, photos, quotes, commentary, and a few extra songs. It was quite clear from reading the essay-like liner notes that lots of people had lots to say about this Cash record.

The title, Bitter Tears: Ballads of the American Indian, prompted a question: What had Cash been up to? I looked at the recording date: 1964. Barely a year earlier, Cash had scored one of his biggest hits ever with Ring of Fire. But the year added another layer of intrigue to the story, for it was a bellwether year in U.S. history. The headlines shouted about the Beatles, Muhammad Ali, the Vietnam War, the Newport Folk Festival, and Martin Luther King Jr.; the Johnson-Goldwater presidential election, the Civil Rights Act, Johnsons Great Society, and the early stirrings of what a few years later would become known as Red Powertaking its cue from the term Black Powerthe Native movement that took hold in the 1960s and grew in the 1970s among Native people. Recorded four years before Cashs Folsom Prison performance and the American Indian Movements takeover of Alcatraz Island, Bitter Tears was released smack in the middle of the roiling civil rights movement and escalating war in Vietnam. In the face of such momentous change and conflict, an album sympathetic to Native peoples issues and their seemingly never-ending search for justice now seemed to me both a compelling and a daring undertaking. At the time, Cash was a music superstar. What kind of response did he get to this album? How did the radio stations respond to a musician who was giving voice to an oppressed group fighting to be heard? A thousand more questions began swirling in my mind, but one was at the root of them all: Why did Cash make this record?

THERE WAS only one way to start finding out, so I lifted the plastic turntable cover, selected the proper setting, placed the record, side 2-up, on the turntable, and moved the needle over to the first song. I pulled the earphones securely over my ears, pushed play, and listened. Soon my head filled with the sound of a flute slowly and hauntingly playing the last bars of taps, immediately calling funeral, wreath-laying, and memorial services to my mind. After more than ten seconds, Cashs deep, husky voice came in, singing the name Ira Hayes, Ira Hayes, quivering over the second Ira as he strummed the first few chords of the song on his D-28 Martin guitar. Soon, Cash was joined by soulful backing vocals for what turned out to be the refrain of the song:

Call him drunken Ira Hayes

He wont answer anymore

Not the whiskey-drinkin Indian

Or the marine that went to war

These lyrics are the opening lines to Ballad of Ira Hayes, clearly a folksong but not in the traditional sense popularized by The Carter Family in the 1920s and 1930s. Ballad of Ira Hayes is instead very much a product of the folk revival that was occurring in the 1960s. As the record spun on the turntable, I could sense Woody Guthries spirit embedded in the grooves. I knew Cash had great feeling for Guthrie, who himself had idolized The Carter Family. I could feel the three distinct musical legends, each with family members who became important musicians in their own rightThe Carter Family, Woody Guthrie, and Johnny Cashcoming together to form one unique folk family tree. The topical folksong movement, as it was called, famously produced scores of musicians who were Guthrie disciples, with Bob Dylan pushing the movement to the forefront of Americas consciousness. Its articulate, impassioned goodwill ambassador was Pete Seeger, but other musicians who walked the streets of Greenwich Village during the folk revival were righteous soldiers of conscience, armed with acoustic guitars and songs telling stories that sought a new America. Judy Collins, Tom Paxton, Buffy Sainte-Marie, Mark Spolestra, Guy Carawan, John Cohen, Len Chandler, and Joan Baez were some of the major voices in this growing U.S. counterculture chorus. Ballad of Ira Hayes is a graphic, poetic account of a Pima named Ira Hayes who goes off to war, becomes a war hero, and then returns home to eventually die an ignoble death blanketed by pain, abandonment, and humiliation. Hayes was not only a Pima who fought in World War II, but he had actually been immortalized in the famous photo of the flag-raising at Iwo Jima. But when I listened to the song that day, I didnt know Ira Hayes from Von Hayes, a second-rate baseball player on my hometown team, the Philadelphia Phillies, in the 1980s. So much for immortality.