Copyright 2006 by Rita Williams

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced

or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical,

including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and

retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work

should be mailed to the following address: Permissions Department,

Harcourt, Inc., 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, Florida 32887-6777.

www.HarcourtBooks.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows:

Williams, Rita (Rita Ann)

If the creek don't rise: my life out West with the last Black

widow of the Civil War/Rita Williams.1st ed.

p. cm.

1. Williams, Rita (Rita Ann) 2. African American

womenBiography. 3. African AmericansBiography.

4. ColoradoBiography. I. Title.

E185.97.W73A3 2006

978.8'00496073092dc22 2006000335

ISBN 978-0-15-101154-4

ISBN 978-0-15-603285-8 (pbk.)

Text set in Fournier

Designed by Cathy Riggs

Printed in the United States of America

First Harvest edition 2007

K J I H G F E D C B A

The valley spirit never dies;

It is the woman, primal mother.

Her gateway is the root of heaven and earth.

It is like a veil barely seen.

Use it; it will never fail.

L AO T SU

Don't go opening your mouth about things

that's none of your business. Hush up.

Hold your mud.

D AISY

1. Playback

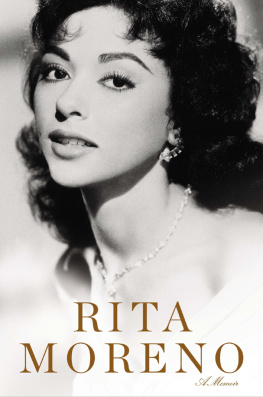

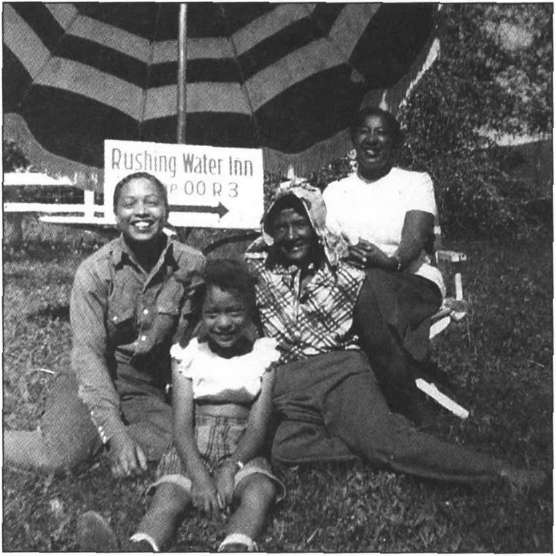

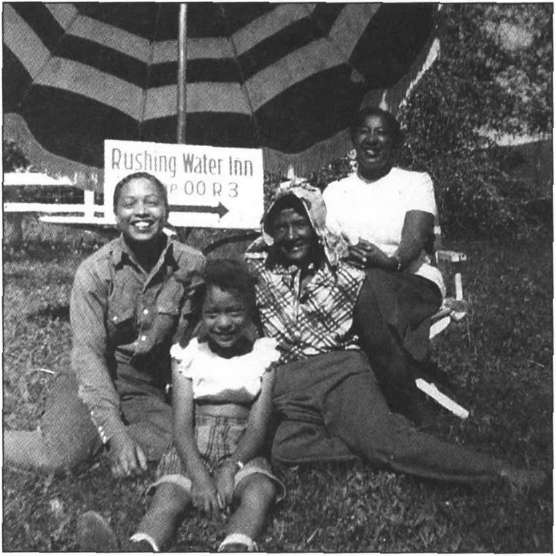

My sister Mary, me, Daisy, and my mother in Strawberry Park

Out my kitchen window, the November wind off the Pacific whipped up light frothy waves on Silver Lake. The oddly beautiful smog-seasoned light burnished the last of the lemons, making them look sweeter than they were. I was just spritzing juice on a bowl of raspberries when my cat, Banana Sanchez, cool from her dalliance in the garden, settled to warm herself on the answering machine downstairs. The playback button engaged. I heard a familiar gravid throat clearing, a deep breath and a sigh.

"Rita? This is Rose." A pause, as if waiting to see if I'd pick up. I didn't. "All right, here it is. Daisy called Mary and Mary called me and I'm calling you. Daisy say she fixin to die. You got to come." Still another pause, in which my oldest sister seemed to be calculating how frank to be on the machine. "Don't know what you aimin to do, but I ain't goin no place."

An abyss opened up right there over the cutting board. Backed up against the Pacific, with two decades between me and my life in Steamboat Springs, Colorado, I still felt the same numb fright at a summons from Daisy that I'd felt when I first went to live with her at the age of four. The odds that Daisy was truly "fixin to die" right now were slim. She had been playing that card for as long as I could remember. But I'd always known I'd have to go back once more, as an adult. And Daisy was in her nineties. Even she couldn't live forever. It was time.

I called the airline and bought a nonrefundable ticket. Then I called the hospital and asked to speak to my aunt.

"I'm sorry, ma'am," the nurse said. "Mrs. Anderson took and checked herself out last week." There was no need to add, "Against doctor's orders."

I had to laugh. Daisy had probably made those deathbed phone calls to Rose and Mary from her home phone in Hayden. Nothing terrified her more than being caged, and no pain was more excruciating than the prospect of entrusting her body to a doctor. She would have threatened to sue the nurses, the hospital, the janitors, the entire town of Steamboat Springs to get herself out.

I dialed Daisy's number and waited, imagining her creeping toward the phone. She picked up on the eighth ring. "Hell-oo?" She still hollered into the receiver as if she had to make her voice carry all the way to California.

"Daisy, it's Rita."

"Reeter Ann Williams? Good land." Her voice sounded higher than it had six months ago, more pushed.

"Heard you needed some help. I'll be coming in Friday night late. Won't probably see you till Saturday morning."

"Well, I'll make up the bed and thaw out a rabbit."

"Yes, ma'am," I said. No need to start a fight right off by telling her that I intended to "waste good money" on lodging and a rental car. "I'll call you when I get to town."

"Well, I'm fixin to sell my books at the Christmas sale Saturday." I had to bite my tongue not to ask whether she meant to sell them from her deathbed, the priest standing by to deliver the final sacrament.

"Okay, I'll help you," I said, and I got off the phone, noticing that that old feeling had me in its spell, that sensation of sparring and dodging out of range.

I'd forgotten what it was like to fly into Steamboat Springs. The prop planes that looked so big on the tarmac at Denver International shrank against the fourteen-thousand-foot blade-sharp peaks of the Continental Divide. My breath grew shallow as the engines ground to the top of their range and the aircraft began to hop around like a waterdrop on a hot griddle. I always managed to fly in just ahead of a storm.

Only twelve other passengers could ride this little prop plane, mainly skiers accustomed to Rocky Mountain turbulence. Across the aisle, a kid in a ski hat was engrossed in an electronic toyprobably a snowboarder planning to spend Thanksgiving on the curl. A businesswoman was equally engrossed by the screen of her laptop. Only the working man with a white swath across his forehead where his tan ended and his cap began stared rigidly at the seat back in front of him, as if he too was holding his breath.

At last the pilot throttled back for the descent, and the plane took to bucking as if it had no intention of setting its wheels down anywhere near Steamboat Springs. I could not shake the image of a search party coming upon the wreckage of the aircraft and our bodies frozen among the pines of Berthoud Pass. Finally we broke cloud cover and the Yampa Valley lay below us.

My hometown was transformed. An infestation of shingled condos extended from the edge of the highway to the base of Mount Werner. The mountain face itself had been given over completely to the service of skiers, hundreds of wide gores scoring its flanks to create ski runs. I remembered when it was lowly Storm Mountain, debuting as a ski resort with a tattered little rope tow on a slope groomed by an orange snowcat. Daisy had been quite confident it would go belly-up in a season. But now I could see significant expansion on either side of Steamboat Springs. Wryly, I thought of an old sixties bumper sticker: Don't Californicate Colorado.

The plane lit on the icy runway, crow-hopped a little to the left, righted itself, reversed thrust. "Made it in before the blizzard," the pilot said over the PA when he'd brought us to a stop.

I walked down the stairs to the tarmac and rolled my little suitcase past what I could have sworn was the site of the A&W stand where I spent my saved allowance on my first root beer float. The arctic air clutched my throat. Hadn't felt that particular nip in a while. I hurried toward the tiny shed of a terminal, smaller than a single luggage carousel at LAX.

Inside, a wall was devoted almost entirely to snowboards. Where were the skis? But a surge of delight went through me as I saw the sensible face of a woman who had to be a Steamboat local behind the car rental counter. At seven thousand feet of constant sun and wind, people wrinkle early, and here was a woman like those I'd grown up with, more concerned with what she was doing than how she looked doing it. The wings on her eyeglasses hooked to the frame at the bottoma style that had died out at least twenty years ago. Her hair had faded to the color of a weathered barn. She wore a tired white turtleneck under a plaid wool shirt, layers to protect her core. The label on her pocket protector read SUSAN . Something about the steadiness of her mien was familiar. Was she one of the Buchanan girls?

Next page