ElectricStory.com

www.electricstory.com

Copyright 1994 by John Crowley

NOTICE: This work is copyrighted. It is licensed only for use by the original purchaser. Making copies of this work or distributing it to any unauthorized person by any means, including without limit email, floppy disk, file transfer, paper print out, or any other method constitutes a violation of International copyright law and subjects the violator to severe fines or imprisonment.

CONTENTS

ISBN: 1-930815-19-0

ElectricStory.com and the ES design are trademarks of ElectricStory.com, Inc.

This novel is a work of fiction. All characters, events, organizations, and locales are either the product of the author's imagination or used fictitiously to convey a sense of realism.

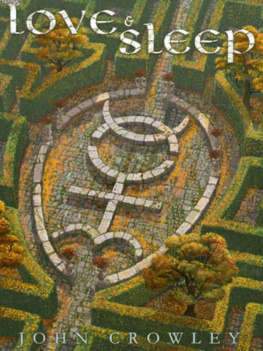

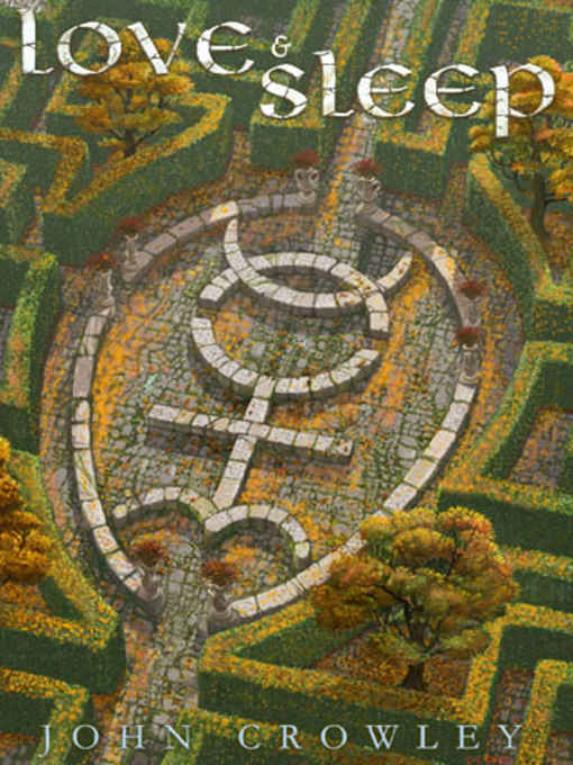

Cover art copyright 2001 by Cory and Catska Ench.

Edited by Ron Drummond.

eBook conversion by Robert Kruger and Lara Ballinger.

eBook edition of Love & Sleep copyright 2001 by ElectricStory.com.

For our full catalog, visit our site at www.electricstory.com.

Love and Sleep

By John Crowley

ElectricStory.com, Inc.

Thou wouldst not think how ill all's here about my heart.

Hamlet

Prologue: To the Summer Quaternary

Once, the world was not as it has since become.

Once it worked in a way different from the way it works now; its very flesh and bones, the physical laws that governed it, were ever so slightly different from the ones we know. It had a different history, too, from the history we know the world to have had, a history that implied a different future from the one that has actually come to be, our present.

In that age (not really long ago in time, but long ago in other bridges crossed, which we shall not return by again), certain things were possible that are not now; and contrariwise, things we know not to have happened indubitably had then; and there were other differences large and small, none able now to be studied, because this is now, and that was then.

Actually, the world ("the world": all this; time and space; past, present, future; memory, stars, correspondences, physics; possibilities and impossibilities) has undergone such an agony more than once, many times maybe within the span of human life on earth, as we measure that life now in our age. And whenever it does happen, there comes a brief momenta moment just as the world turns from what it has all along been into what it will from then on bea brief time when every possible kind of universe, all possible extensions of Being in space or time, can be felt, poised on the threshold of becoming: and then the corner is turned, one path is taken, and all of those possibilities return into nonexistence again, except for one, this one. The world is as we know it now to be, and always has been: everyone forgets that it could be, or ever was, other than the way it is now.

If this were soif it were really sowould you be able to tell?

Even if you somehow came to imagine that it was so; ifseized by some brief ecstasy in a summer garden, or on a mountain road in winteryou found yourself certain it was so, what evidence or proof could you ever adduce?

Suppose a man has crossed over from one such age of the world into the next (for the passage-time might not be long, not centuries; a life begun in the former time might well reach across the divide into the succeeding one, and a soul that first appeared under certain terms might come of age and die under others). Suppose that, standing on the farther shore, such a man turns back, troubled or wondering, toward where he once was: wouldn't he be able to perceivein the memories of his own body's life, the contents of his own beingthis secret history?

Maybe not; for his new world would seem to have in it all that he remembers the old world to have had; all the people and places, the cities, towns, and roads, the dogs, stars, stones, and roses just the same or apparently the same, and the history likewise that it once had, the voyages and inventions and empires, all that he can remember or discover.

Like a mirror shaken in a storm, in the time of passage memory would shiver what it reflects into unrecognizability, and then, when the storm was past, would restore it, not the same but almost the same.

Oh there would be small differences, possibly, probably, differences no greater than those little alterationswhimsical geographies, pretend books, names of nonexistent commercial productsthat a novelist introduces, to distinguish the world he makes from the diurnal real, which his readers supposedly all share: differences almost too small to be discovered by memory, and who nowadays trusts memory anyway, imperious, corrosive memory, continuously grinding away or actually forcing into being the very things it pretends only to shelter and preserve.

No: Only in the very moment of that passage from one kind of world to the next kind is it ever possible to discover this oddity of time's economy. In that moment (months long? years?) we are like the man who comes down around the bend into his hometown and discerns, rising beyond the low familiar hills, a new range of snowy alps. Brilliant, heart-taking, steep! No they are clouds, of course they are, just cast momentarily for some reason of the wind's and weather's into imitation mountains, so real you could climb them, this is just what your homeland would be if its hills were their foothills. But no, the blue lake up on those slopes, reflecting the sky, is the sky seen through a rent, you will never drink from it; the central pass you could take upward, upward, is already beginning to tatter and part.

Pierce Moffett (standing on a winter mountain road, in his thirty-sixth year, unable just for the moment to move either onward or back, but able to feel the earthball beneath his feet roll forward in its flight) remembered how when he was a boy in the Cumberland Mountains of Kentucky he and his cousins had taken in a she-wolf cub, and kept it hidden in their rooms, and tried to tame it.

Now had he really done such a thing? How could he even ask this question of himself, when he could remember the touch of it, how he had cared for it, fed it, baptized it?

He remembered how in those days he had known the way to turn a lump of coal into the diamond that it secretly is, and had done it, too, once; remembered how he had discovered a country beneath the earth, which could be reached through an abandoned mine. He remembered the librarian of the Kentucky State Library in Lexington (Pierce could just then see her clearly, within her walls of dark books, a chain on her glasses), how she had set him a quest when he was a boy, a quest he had embarked on willingly, knowing nothing, not how far it would take him, nor what it would cost him. A quest he was sure now he would not ever complete.

He had once set a forest on fire, so that a woman he loved could see it burn, a woman who loved fire. Hadn't he?

O God had he actually once for her sake killed his only son?

But just then the road upward began to unroll again, and took Pierce's feet along with it; and he mounted a little farther toward the summit, where there was a monument he had heard of, but hadn't ever seen. The sun rose, in a new sign. Looking down at his feet, Pierce saw in wonder and dread that he was wearing mismatched shoes, almost the same but not the same. He had walked a couple of miles and more from home without noticing.

* * * *

But it might be felt differently; indeed it would have to be felt differently, the last age ending and the new coming into being, felt differently by every person who passes through the gates.