For my dad,

who showed me how to love football,

and my mum,

who hates it

Contents

Those who know nothing of foreign languages know

nothing of their own.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

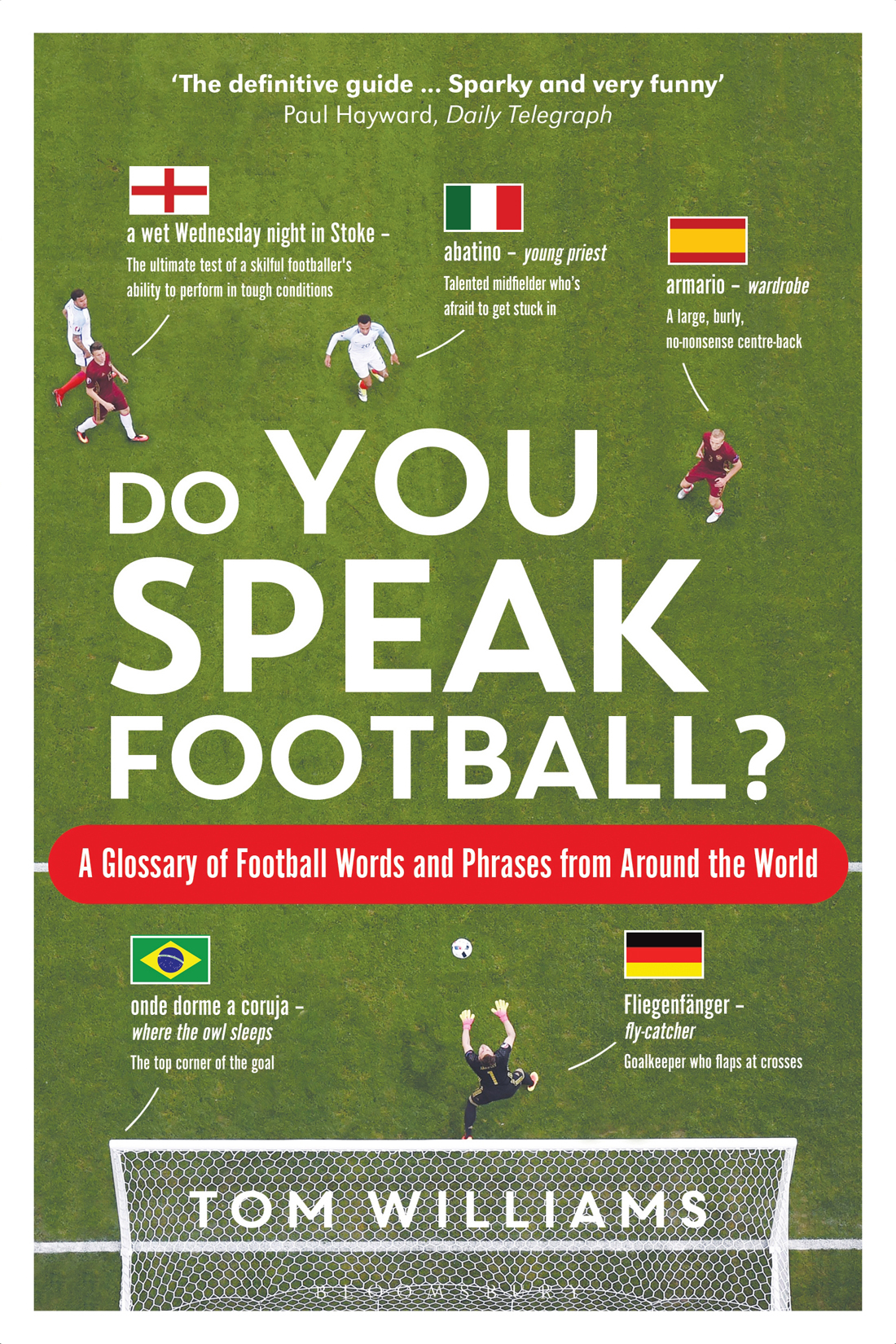

Football, its often said, is a universal language, but while you might not need any specialist vocabulary to play it or watch it, how about to discuss it? Would you know what an Italian meant if they told you someone had scored with a spoon? Why a Ukrainians mouth might water at the prospect of a biscuit with raisins? Why you really wouldnt want to be called a Dundee United by someone from Nigeria?

The story of football is the tale of a sport spawned on the muddy school playing fields of Victorian England that carried itself into the hearts of people in every country on the planet. The words in this book are the words of that tale. No countrys football story is the same, each nations experience of the game being refracted through the unique prism of its language. Hold each prism to your eye and football reveals itself in strange, amusing and unexpected ways.

The language of Spanish football bears traces of the bullring. We find fragments of cricket in England, while American football, baseball and basketball loom large in the United States. Animals lope, slither and fly across our path everywhere we go: bears in Finland, snakes in Kenya, elephants in Indonesia, zebras (somewhat incongruously) in Brazil. In Argentina, a diving header is known as a little pigeon. In the Indian state of Kerala, a crafty forward is likened to a specific local species of fish.

A technically limited player might have a wooden leg (Brazil), a wooden foot (Paraguay) or be made of wood entirely (Serbia). In Spain a bulky defender is a wardrobe, in Tanzania a padlock and in Saudi Arabia a safety valve.

The home and, in particular, the kitchen provide a plentiful supply of metaphors. Depending on where you are in the world, a spectacular long-range shot could be likened to a banana, a cucumber, a potato or a croissant. A Dutch player who attempts a shot with his weaker foot is said to have used his chocolate leg. Thanks to Roy Keane, corporate fans in Britain are known as the prawn sandwich brigade. In France, home of the worlds finest gastronomy, what else would you call a perfectly delivered through ball that begs to be gobbled up but un caviar ?

The language of football springs from many sources. Lots of terms have leaped from neighbourhood pitches and school playgrounds. Some owe their existence to iconic players, historic goals or notorious incidents. We also hear echoes of the voices of influential journalists and commentators, such as Ricardo Lorenzo Rodrguez, better known as Borocot, whose editorship of sports magazine El Grfico shaped Argentinas attitude towards football in the first half of the 20th century. Or Gianni Brera, who mapped every hill, valley, highway and byway in the landscape of post-war Italian football.

Every football culture under the sun has a word for the singularly humiliating act of sticking the ball between an opponents legs, which is known as a nutmeg in the English-speaking world, a panna (gate) in the Netherlands and variously as an egg, a bridge, a pen, a violin, a salad or a gherkin to cite but six examples elsewhere. The same is true to a slightly lesser extent of the goals top corners (often described in terms of spiders and cobwebs) and jittery goalkeepers (lettuce hand in Brazil, porridge fingers in Estonia, flying buffalo in Turkey).

Referees, naturally, get it in the neck everywhere. A referee suspected of being crooked is branded a black whistle in China. A hopeless match official in Malaysia will be told that hes a blockhead. In the Soviet Union, fans aggrieved at a referees performance would call for the man in black to be turned into a bar of soap a sinister nod to the Soviet practice of using the bodies of stray dogs to make cosmetic products.

Several countries, among them Italy, Spain and Russia, employ a term from the card table poker when a player puts the ball into the net four times in the same game. Nicknames for the ball itself abound, although they tend to be rather more poetic in South America gorduchinha , meaning little pudgy one, is one example from Brazil than in Europe, where the leather is often the default metaphor.

The internet is changing the way that new terminologies emerge, and has concurrently engendered an increase in the use of English as a conduit for new coinages. If Britain laid down footballs linguistic foundations (corner, free-kick, offside, even football itself) and then stepped away as foreign cultures arrived to carry out the brickwork ( rabona , panenka , sombrero ), the status of English as the lingua franca of the online world has brought the sports native language back to the building site.

The phenomenon can be seen in freestyle football and street football, where many of the new tricks and moves that have emerged over the past 15 years curated in widely viewed YouTube videos and disseminated via social media have been assigned English names. Manoeuvres like the mouse trap, the air akka and the mesmomeg are too convoluted even for the most skilful elite players to attempt in a match, but altogether they represent a new column in footballs linguistic development, where elements of the games future vocabulary already exist and are just waiting for the sport to catch up.

Since football fans are uniquely sensitive to the language used to describe their sport, it should be acknowledged that some of the terms in this book may have alternative meanings in different regions or countries. Language drifts like smoke across borders and all countries pinch terms, magpie-like, from beyond their own frontiers, so its for the sake of convenience that some words and phrases have been listed beneath the flag of a certain country.

Much of the language of Spanish football, for example, will be familiar to people from Hispanic America, and vice versa. There is inevitable crossover between the football vocabularies of Portugal and Brazil, Belgium and the Netherlands, France and Francophone Africa, Britain and her former colonies, and among the many nations of the Arab world.

This is by no means an exhaustive glossary, and youre invited to flag up omissions by joining the conversation at the hashtag #doyouspeakfootball (where youll also find related pictures and videos). The aim of the book is merely to offer a flavour of the myriad ways in which football is talked about around the world. As you will discover in the pages that follow, to truly speak football is to speak a language of a thousand tongues.

Tom Williams

www.twitter.com/tomwfootball

A riot of noise, colour and skill, South American football is characterised by both the steely guile of Argentina and the vivacious technical artistry of Brazil. From Uruguays 1924 Olympic champions to the fabled Brazil XI that elevated the sport to unparalleled heights at the 1970 World Cup, South America has furnished football with some of its most magnificent teams, and in men like Pel, Diego Maradona, Ronaldo and Lionel Messi, it has gifted us the games very greatest players.

Spanish is the first language in most of the countries of South America the legacy of Spains colonisation of the Americas but the huge population of Brazil (208 million at the last count) means that Portuguese is the continents majority language.