Table of Contents

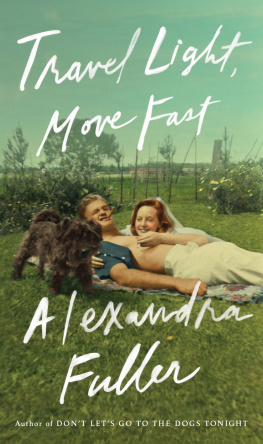

TO MUM, DAD, AND VANESSA

AND TO THE MEMORY OF ADRIAN, OLIVIA, AND RICHARD

with love

Dont lets go to the dogs tonight,

For mother will be there.

A. P. HERBERT

Bobo loading the FN

RHODESIA,

1976

Mum says, Dont come creeping into our room at night.

They sleep with loaded guns beside them on the bedside rugs. She says, Dont startle us when were sleeping.

Why not?

We might shoot you.

Oh.

By mistake.

Okay. As it is, there seems a good enough chance of getting shot on purpose. Okay, I wont.

So if I wake in the night and need Mum and Dad, I call Vanessa, because she isnt armed. Van! Van, hey! I hiss across the room until she wakes up. And then Van has to light a candle and escort me to the loo, where I pee sleepily into the flickering yellow light and Van keeps the candle high, looking for snakes and scorpions and baboon spiders.

Mum wont kill snakes because she says they help to keep the rats down (but she rescued a nest of baby mice from the barns and left them to grow in my cupboard, where they ate holes in the familys winter jerseys). Mum wont kill scorpions either; she catches them and lets them go free in the pool and Vanessa and I have to rake the pool before we can swim. We fling the scorps as far as we can across the brown and withering lawn, chase the ducks and geese out, and then lower ourselves gingerly into the pool, whose sides wave green and long and soft and grasping with algae. And Mum wont kill spiders because she says it will bring bad luck.

I tell her, Id say we have pretty rotten luck as it is.

Then think how much worse it would be if we killed spiders.

I have my feet off the floor when I pee.

Hurry up, man.

Okay, okay.

Its like Victoria Falls.

I really had to go.

I have been holding my pee for a long, long time and staring out the window to try and guess how close it is to morning. Maybe I could hold it until morning. But then I notice that it is the deep-black-sky quiet time of night, which is the halfway time between the sun setting and the sun rising when even the night animals are quietas if they, like day animals, take a break in the middle of their work to rest. I cant hear Vanessa breathing; she has gone into her deep middle-of-the-night silence. Dad is not snoring nor is he shouting in his sleep. The baby is still in her crib but the smell of her is warm and animal with wet nappy. It will be a long time until morning.

Then Vanessa hands me the candleYou keep boogies for me nowand she pees.

See, you had to go, too.

Only cos you had to.

There is a hot breeze blowing through the window, the cold sinking night air shifting the heat of the day up. The breeze has trapped midday scents; the prevalent cloying of the leach field, the green soap which has spilled out from the laundry and landed on the patted-down red earth, the wood smoke from the fires that heat our water, the boiled-meat smell of dog food.

We debate the merits of flushing the loo.

We shouldnt waste the water. Even when there isnt a drought we cant waste water, just in case one day there is a drought. Anyway, Dad has said, Steady on with the loo paper, you kids. And dont flush the bloody loo all the time. The leach field cant handle it.

But thats two pees in there.

So? Its only pee.

Agh sis, man, but itll be smelly by tomorrow. And you peed as much as a horse.

Its not my fault.

You can flush.

Youre taller.

Ill hold the candle.

Van holds the candle high. I lower the toilet lid, stand on it and lift up the block of hardwood that covers the cistern, and reach down for the chain. Mum has glued a girlie-magazine picture to this block of hardwood: a blond woman in few clothes, with breasts like naked cow udders, and shes all arched in a strange pouty contortion, like shes got backache. Which maybe she has, from the weight of the udders. The picture is from Scope magazine.

We arent allowed to look at Scope magazine.

Why?

Because we arent those sorts of people, says Mum.

But we have a picture from Scope magazine on the loo lid.

Thats a joke.

Oh. And then, What sort of joke?

Stop twittering on.

A pause. What sort of people are we, then?

We have breeding, says Mum firmly.

Oh. Like the dairy cows and our special expensive bulls (who are named Humani, Jack, and Bulawayo).

Which is better than having money, she adds.

I look at her sideways, considering for a moment. Id rather have money than breeding, I say.

Mum says, Anyone can have money. As if its something you might pick up from the public toilets in OK Bazaar Grocery Store in Umtali.

Ja, but we dont.

Mum sighs. Im trying to read, Bobo.

Can you read to me?

Mum sighs again. All right, she says, just one chapter. But it is teatime before we look up from The Prince and the Pauper.

The loo gurgles and splutters, and then a torrent of water shakes down, spilling slightly over the bowl.

Sis, man, says Vanessa.

You never know what youre going to get with this loo. Sometimes it refuses to flush at all and other times its like this, water on your feet.

I follow Vanessa back to the bedroom. The way candlelight falls, were walking into blackness, blinded by the flame of the candle, unable to see our feet. So at the same moment we get the creeps, the neck-prickling terrorist-under-the-bed creeps, and we abandon ourselves to fear. The candle blows out. We skid into our room and leap for the beds, our feet quickly tucked under us. Were both panting, feeling foolish, trying to calm our breathing as if we werent scared at all.

Vanessa says, Theres a terrorist under your bed, I can see him.

No you cant, how can you see him? The candles out.

Struze fact.

And I start to cry.

Jeez, Im only joking.

I cry harder.

Shhh, man. Youll wake up Olivia. Youll wake up Mum and Dad.

Which is what Im trying to do, without being shot. I want everyone awake and noisy to chase away the terrorist-under-my-bed.

Here, she says, you can sleep with Fred if you stop crying.

So I stop crying and Vanessa pads over the bare cement floor and brings me the cat, fast asleep in a snail-circle on her arms. She puts him on the pillow and I put an arm over the vibrating, purring body. Fred finds my earlobe and starts to suck. Hes always sucked our earlobes. Our hair is sucked into thin, slimy, knotted ropes near the ears.

Mum says, No wonder you have worms all the time.

I lie with my arms over the cat, awake and waiting. African dawn, noisy with animals and the servants and Dad waking up and a tractor coughing into life somewhere down at the workshop, clutters into the room. The bantam hens start to crow and stretch, tumbling out of their roosts in the tree behind the bathroom to peck at the reflection of themselves in the window. Mum comes in smelling of Vicks VapoRub and tea and warm bed and scoops the sleeping baby up to her shoulder.

Next page