Copyright 2006 by Tim Bascom

Foreword copyright 2006 by Ted Hoagland

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

hmhbooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bascom, Tim, date.

Chameleon days : an American boyhood in Ethiopia / Tim Bascom.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN -13: 978-0-618-65869-5 (alk. paper)

ISBN -10: 0-618-65869-6 (alk. paper)

1. Bascom, Tim, dateChildhood and youth. 2. Ethiopia

HistoryRevolution, 1974 Personal narratives, American.

3. EthiopiaDescription and travel. 4. AmericansEthiopia

Biography. 5. MissionariesEthiopia. I. Title.

DT 387.95. B 365 A 3 2006

963.06092dc22 2005031530

eISBN 978-0-547-34647-2

v2.0719

The following chapters were previously published: Baboons on a Cliff, in

Boulevard; And Ill Fly Away, Florida Review, winner of the 2004 Florida

Review Editors Prize in Nonfiction; A Vocabulary for My Senses, Missouri

Review, winner of the 2003 Missouri Review Editors Prize in Essay, also

published in Best American Travel Writing 2005.

The following songs are quoted with permission: Surely Goodness and Mercy

by John W. Peterson / Alfred B. Smith. Copyright 1958 Singspiration Music

(ASCAP) (Administered by Brentwood-Benson Music Publishing, Inc.).

All rights reserved. Used by permission. His Sheep Am I by Orien John

son. Copyright 1956 Orien Johnson, assigned to Sacred Songs (Division

of Word, Inc.). All rights reserved. Used by permission.

All photos taken by Kay or Charles Bascom and reprinted with permission.

This book is dedicated to the many

missionary children, known and unknown,

who carry their own stories inside them.

In particular, it is dedicated to

my brothers, John and Nat, and to my

lifelong friend Daniel Coleman.

Foreword

AFRICA , the site of our primeval origins, possesses as a consequence enormous reverberations for many Westerners and Northerners. The beauty, magnetism, risk, and potentiality beckon ambiguously, however, because alongside the kaleidoscope of noble skyscapes and splendid fauna bespattering the veldt can lie a parallel reality of famine and pandemics, or horrific politics. And if the imagery becomes phantasmagoric, this isnt China, but our Africa!

In Chameleon Days, Tim Bascom recalls being airlifted at the age of three from his early childhood in Saint Joseph, Missouri, to Soddo, Ethiopia, by vaguely dogmatic missionary parents. That alchemya childs-eye view of arduous immediacyis maintained quite admirably in his memoir, forty years later, thus breaching the standard traditions of travel writing. Although his father was a doctor, not merely an evangelist, his medical responsibilities theoretically encompassed a hundred thousand patients. So the row they hoed was not easy, and the family did burn out during a second tour of duty, leaving prematurely, although both the author and his parents returned in later life.

But its an Africa of basics, not numinous romance: a tale well-grounded in a little boys close-grained focus on apprehensive innocence and vulnerability. Theres heat and cruelty, kindness and leprosy, revolution and elephantiasis. Yet since a lot of Tims ex periences are located in the missionary boarding school in Addis Ababa where he was often marooned, for him it may be even more conflicted and scary, with the kinks and quirks of Orwells Such, Such Were the Joys added on.

There is logic and mercy in Africa too, and these peep through during the Bascoms hapless, jolting Land Rover excursions, and in new friendships, along with the contradictions between what missionaries want to accomplish yet need to shut their eyes to. Charity must keep office hours, or a nervous breakdown could wipe the family out. Tim climbs into a cedar tree for a personal refuge at Bingham Academy, and into the foliage of a huge avocado tree in Soddo (while eating avocado sandwiches his mother makes for him) to escape what seems untenable. He even spies upon the Lion of Judah, Emperor Haile Selassie himself, from its leaves.

Not a book of war and pestilence, this is about childhood, much of which, for almost any of us, is going to be composed of chameleon days. Tim, however, has a chameleon, plus a loving family to cushion his continental displacement, and now writes with meticulously graceful recapitulation about pet pigeons, or the weaverbirds and snakebirds at Lake Bishoftuturquoise in its volcanic craterwhere they all vacationed.

Africas somersaulting mysteries and difficulties compound this schoolboys natural anxiety at juggling self-respect with popularity, and how to remain a Christian when served by servants, then seeing his omnipotent father rendered puzzlingly powerless by infighting. Place and populace meld here in a lovely narrative, styled for transparency. A childhoods jitters stand recollected in tranquilityand a beloved continent, ruefully enigma-riddled, in maturity.

EDWARD HOAGLAND

Part One

Baboons on a Cliff

AS WE LEFT the Addis Ababa airport and started across the city, my brother Johnathan and I stared out the windows of the Volkswagen van like dazed astronauts. He was six and I was only three, but we were both old enough to sense that life might never be the same. A torrent of brown-skinned aliens streamed by on both sides, treating the road like a giant sidewalk, their white shawls and bright head wraps bobbing as they weaved around each other. Donkeys and oxen bumped into the van, whipped along by barefoot men in ballooning shorts.

After sixteen hours in an airplane, we found that our whole world had disappeared. Gone was the quiet stucco house in Saint Joseph, Missouri, where we had lived while Dad began his medical practice at the state hospital. Gone were the tire-thrumming brick streets of Hiawatha, Kansas, where we were given candies and back-scratches from Grandmother. Gone were the maple trees and the old-fashioned street lamps, lit up like glowing ice cream cones. We had stepped onto a Pan Am jet in one world and stepped off in another, as if transported clear across the galaxy.

Our driver braked for a truck being unloaded, and children pressed their faces against the glass, shouting, Ferengi, ferengi, hey you, my friend, give me money. They left mucous streaks on the windows and patches of breath that faded as we drove on.

Older, broken people approached too, holding out open palms. Gaetoch, gaetoch,they murmured, using the Amharic term for lord. A legless man on a wooden scooter shoved himself into the road and thumped on the sliding door with his tar-stained hand. Next, a fingerless woman thrust her stump through the open window by my father, and my brother Nat, who was not even six months old, began to whimper.

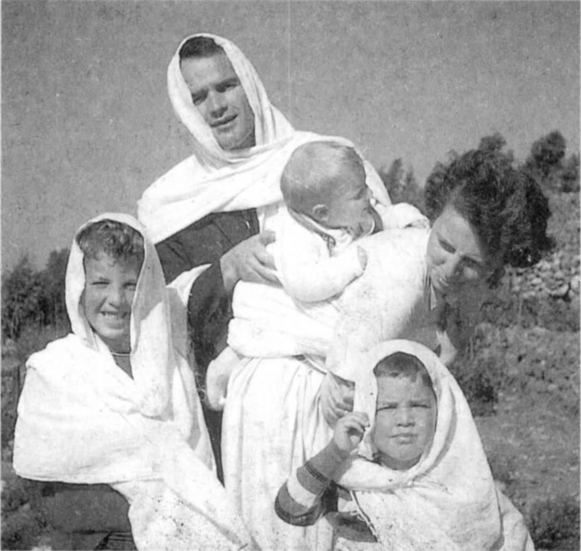

DEBRE BIRHAN, ETHIOPIA , 1964.

The new missionary family. Me in front.

Its OK, Mom whispered, even though Nat was too young to understand. She just wants money.

Whats wrong with her face? I asked, having a three-year-olds curiosity about the womans caved-in nose.

Its leprosy, Dad said. He gave the woman a coin. Then, as the van eased away, he called back to my older brother, Johnathan, do you remember any lepers in the Bible?