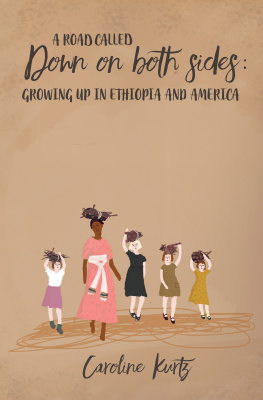

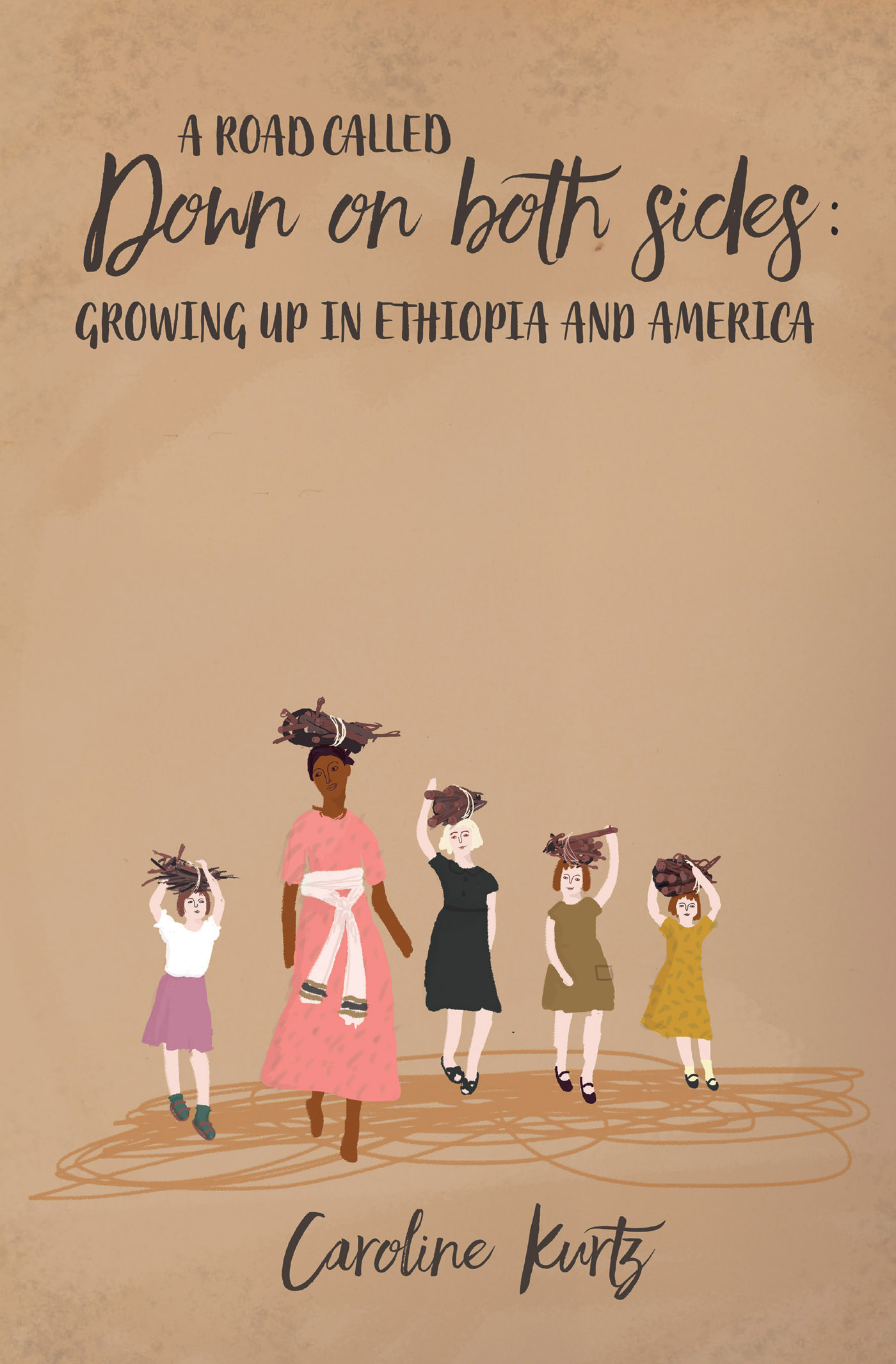

A Road Called Down on Both Sides: Growing up in Ethiopia and America

BY CAROLINE KURTZ

CATALYST PRESS

Livermore, California

Text Copyright Caroline Kurtz, 2019.

Illustration Copyright Karen Vermeulen, 2019.

Part of was printed as an essay,

Comfort Food, in Georgetown Review, Spring 2010

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written consent from the publisher, except for brief quotations for reviews.

For further information, write Catalyst Press,

2941 Kelly Street, Livermore CA 94551

or email

In North America, this book is distributed by

Consortium Book Sales & Distribution, a division of Ingram.

Phone: 612/746-2600

www.cbsd.com

In South Africa, Namibia, and Botswana,

this book is distributed by LAPA Publishers.

Phone: 012/401-0700

www.lapa.co.za

FIRST EDITION

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Control Number 2018964622

Dedicated to Mom, Dad, and Mark, who took me on grand adventures and have now embarked on adventures beyond this earthly form.

Contents

A note of thanks

Before this book went to press, five generous Ethiopian readers gave me their feedback on how I had presented Ethiopian culture and history. The worth of their contribution is incalculable. They corrected my transliterated spelling of Amharic words, and in a few cases corrected my usage. They challenged me into deeper research about the tensions between ethnic groups that I had seen but not fully understood first as a child and later as a teacher in Ethiopia. They corrected misunderstandings that could have seemed embarrassingly ignorant or even hurtful to my Ethiopian friends. The process of working with them has been a new, exciting chapter of learning in my life as a participant in two cultures. Thank you, Dr. Woubeshet Ayenew, for reading my manuscript and passing it on to your mother Wzo. (Mrs.) Zemamnesh Adamu for her feedback as well. She created a chart of Amharic words Id used, what pages they occurred on, and how they should be spelled! Thank you, Dr. Worku L. Mulat, Dr. Fethiya Mahmoud, and Wzo. Zenbaba Fikere for taking the time to read my manuscript and become my friends and teachers. All of you gave me feedback that was beyond invaluable, and made this book a richer, deeper story. Dr. Woubeshet said he was sorry our work together on the book is coming to an end, because our discussions have been so interesting. I totally agree! And as we go to press, I take full responsibility for any remaining mistakes.

Thank you also to Graham Abney, a history graduate student at Portland State University, who did a thorough fact-check of Ethiopian history for me. You saved this big-picture thinker and history lover from several careless mistakes, and from some sweeping statements that, again, might have embarrassed me later!

Caroline Kurtz

June 2019

Portland, Oregon

CHAPTER 1

I grew up in Maji, on the edge of an Ethiopian escarpment that descends, one blue volcanic ridge at a time, to the lowlands of South Sudan. A dirt track ran through the middle of town. People walked to Maji from miles around on market days, and spread the extra their little farms had produced on mats in an open spot beside the track. The clay soil there had been pounded to an impenetrable surface. People used the coins they exchanged, or bills that had grown ragged and brown, to buy the soap, salt, sugar, and candles they couldnt grow. The market square was littered with bits of the leaves people used to wrap butter or enset root; chips off gourds that had held honey or milk; fragrant cow pies in the corner where cattle were sold; and strands of the pithy ribs of enset leaves that people used as twine.

We lived a mile from town, on a knoll overlooking the valley.

One morning over breakfast, when I was about eight, Dad said, Were going on a hike today. Im going to show you a surprise.

He beamed at the two aunties who had arrived the day before. Then he turned his smile on me and my younger sisters, Jane and Joy. Youre going to be amazed!

Mom raised her eyebrows. Amazed? Her skepticism only made the surprise richer.

Tell us, Daddy, Jane said. She was six.

Eat your oatmeal. Itll stick to your ribs.

Above the table, morning light and fresh air came into our dining room between the top of thick mud-plaster walls and our korkoro, or corrugated iron roof. Dad had supervised the building of this home for us. When they poured the cement floor, he polished it to a pewter shine. Mom hung curtains at the windows, peacocks with red tails on a gold ground. Out the window stood the giant thatched roofs of the gojos where wed first lived.

The aunties looked up, interested in this talk of surprises. They werent our real aunties. They were single American women, nurses working in a hot lowland area, come to see the famous mountains of Maji.

A gong sounded to call the workmenDads foreman hitting a battered Jeep wheel rim with a piece of iron pipe. Dad pushed his chair back. Wood scraping on cement echoed off the korkoro. Ill get the men started. Meet me at the gate.

Dad had gone to seminary, but before that hed been a farm boy in Eastern Oregon. Now his life revolved around a shop that smelled of oil, kerosene, and earthwith korkoro walls as well as roof.

Jane, Joy, and I ran out of the house, shoes on and tied. The aunties emerged from the guest-house gojo with walking sticks. They wore long skirts whose colors had faded in the tropical sun, white socks and white blouses, sturdy shoes, and sweaters that protected them against the mountain air we were so used to. Aunt Joan was solid and square and full of effervescent energy. Aunt Breezy had a smile as warm as the sunrise.

They sauntered, chatting, along the track that ran around our house, past the border of heavy-headed Shasta daisies. Jane and Joy each grabbed an aunties hand. I was too big for hand holding. Dad came out of the shop, rubbing his hands together. His smile bunched his cheeks over high cheekbones.

As we descended the foot path outside the gate, I fell into line behind Jane, with her chopped-short hair. Short, because shed screamed when Mom put it in a ponytail. Chopped, because she couldnt sit still while Dad cut it. We picked fern babies off the growing tips of waist-high ferns that grew beside the path. They smelled of chlorophyll and sunshine. Joy trotted ahead of us, the wispy tail on the back of her head bouncing with every step. The Maji air might be warm, with sun beaming down so direct, so near. Or it might be chill with valley fogs. At 8,500 feet, we could depend on the Maji air to always feel thin, always taste fresh. The aunties, from their lowland climate, immediately began to breathe hard.

Jane and I had named the clay outcropping against the opposite hillside Red Rock in a fit of poetic romance, though it was dull pink and smeared with cow pies. Where the two hills swooped together, a little stream threaded over a stone ledge, running to meet the river that fell in stages into the valley. Green moss waved in the faint current. The water trickled softly, and the hollow tonk of hand-carved wooden cow bells from the hillside above us drifted in the clear air.

Dad straddled the creek. Step on my foot, he said to Joy. Now jump! Her ponytail flew and her little red t-shirt hitched up from her elastic-waist jeans as he levitated her to the other side. Jane, dancing with impatience, grabbed Dads arm before he had even turned Joy loose. Hold your horses, he said. She leapt so high that landing dropped her to her knees on the stone.

Next page