I thank early readers for their advice and discerning criticism but claim as my own any Abyssinian idiosyncrasies in the choices retained here. Spellings, however idiosyncratic, have been kept, for the larger part, as in their original renderings, save when they would have presented the reader with unnecessary difficulties. The word Ethiopian will be used throughout this book, where contemporary usage would often divide the people into their smallest common denominators. There is nothing wrong per se in this essentialism Unity in Diversity is after all one of the Federal Republics mottoes. But if Ethiopia has indeed long been famous for its multiplicity, this reductive view seems to hark back to the Italian invaders catalogue-like definition for the country: Ethiopia: the Museum of Peoples. While there is indeed beauty in diversity, the ties that bind are stronger than the dividing chasms that rend the Ethiopian high plateau. The texts anthologised here are of their time and may use vocabulary, or express ideas, in a way that is considered derogatory today. Terms such as Fuzzy-Wuzzy (for Beni Amer), Galla (for Oromo), Falasha (for Beta Israel), or Moor (for Arabs and Muslims), are to be read as historical. Any lack of correction of these terms should in no way be understood as an endorsement of their contemporary usage by the editor or the publishers.

Many thanks to Eloi Ficquet, Solomon Demeke, Lydia Stranger, Abebe Zegeye, Deborah Ghirmai and Fabio Ferraresi for reading first drafts, and to Jean-Michel le Dain (and the French Embassy in Ethiopia) for their willingness to support the translation of a number of texts which were only available to this day in French. The task of sourcing rare travel accounts would have been near impossible without the friendly help of the staff of the libraries of the French Centre for Ethiopian Studies in Kebena, and of the Library of Ethiopian Studies itself, in the melancholic palace that became Addis Ababa Universitys first abode. A number of authors have kindly given their permission for extracts from their books to feature here: Sbastien de Courtois, Hugues Fontaine, Philip Marsden, Dervla Murphy, Kevin Rushby, Ian Campbell, Jacques Mercier, Aberra Jemberes son Nurlin Aberra (and Shama Books), Charlie Walker, Aida Edemariam and Sammy Asfaw. Warm thanks to all of them. Eloi Ficquet also kindly allowed me to use an extract from the Chronicle of the Imans of Wollo that he was yet to publish. We also acknowledge permission to reprint other copyright material as follows: Penguin Books Ltd for permission for the extract from Remote People by Evelyn Waugh ( Evelyn Waugh 1932), Curtis Brown Group Ltd, London on behalf of Thomas Packenham for permission to quote from The Mountains of Rasselas ( Thomas Packenham, 1959), Curtis Brown Group Ltd, London on behalf of the Beneficiary of the Estate of Wilfred Thesiger for permission to use an extract from The Life of My Choice ( Wilfred Thesiger, 1980) and the Guardian for permission to use the article by Aida Edemariam from 1 September 2007.

Remerciements aussi Joseph Stranger for tracking down books; to Rose Baring and Andrew R. Knight for their Gypaetus barbatus-eyed editing, as well as to Yoadan Girma for her impeccable translating and secretarial skills. Special thanks to Richard and Rita Pankhurst, who not only allowed me to quote from Richards book (Travellers in Ethiopia), but also to republish here his informative article on Caves Around Addis Ababa from the Ethiopian Observer. Et un grand merci Mark Ellingham, from Sort of Books without whom the library of Mount Abora would have continued to lack an indispensable, if necessarily summary, appendix.

Y-M S

Contents

Introduction

Can the Ethiopian change his skin can the leopard change its spots?

JEREMIAH 13:23

Jorge Luis Borges who once wrote a fable called The Immortal that began and circuitously ended inside the margins of Ethiopia set forth that all good authors create their precursors. In turn, following in his footsteps, one could venture to say that all countries worth their salt create their own geography from myths, old maps and wishful thinking.

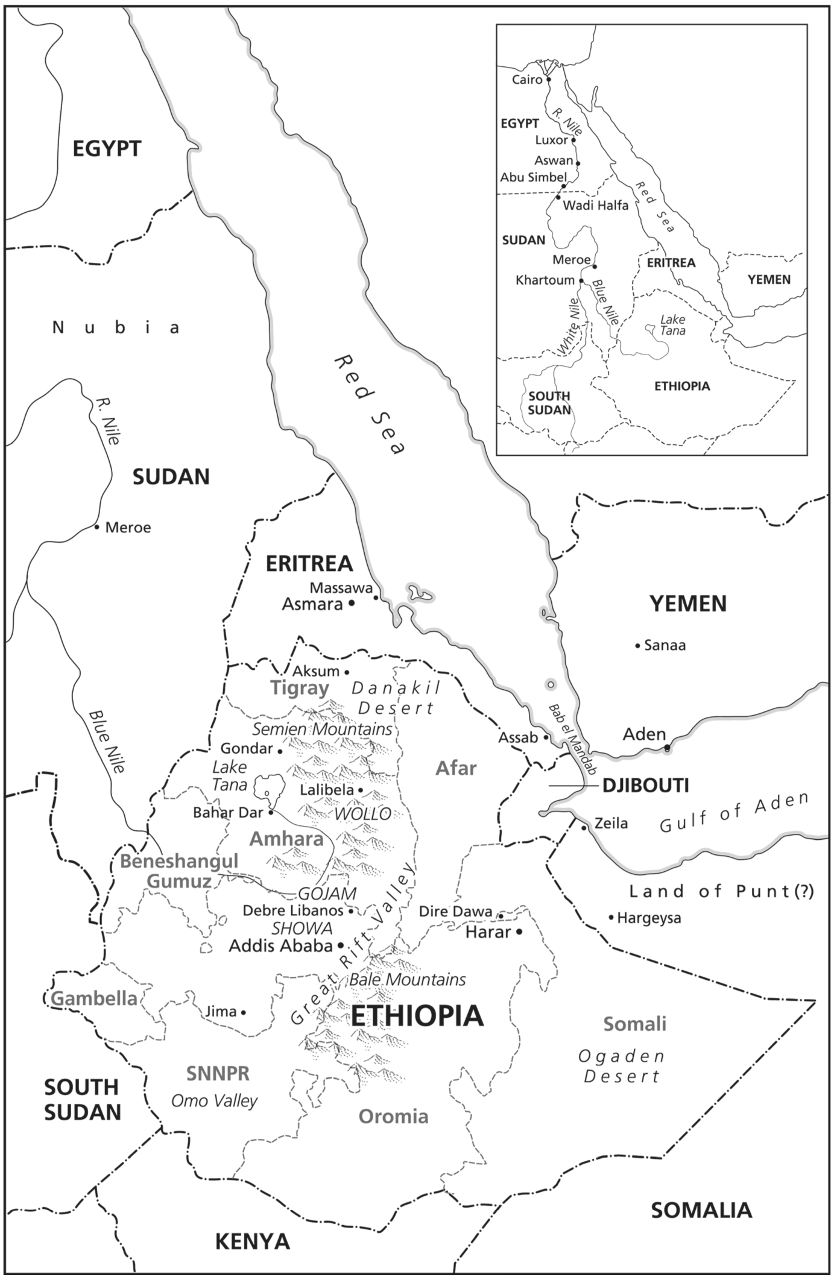

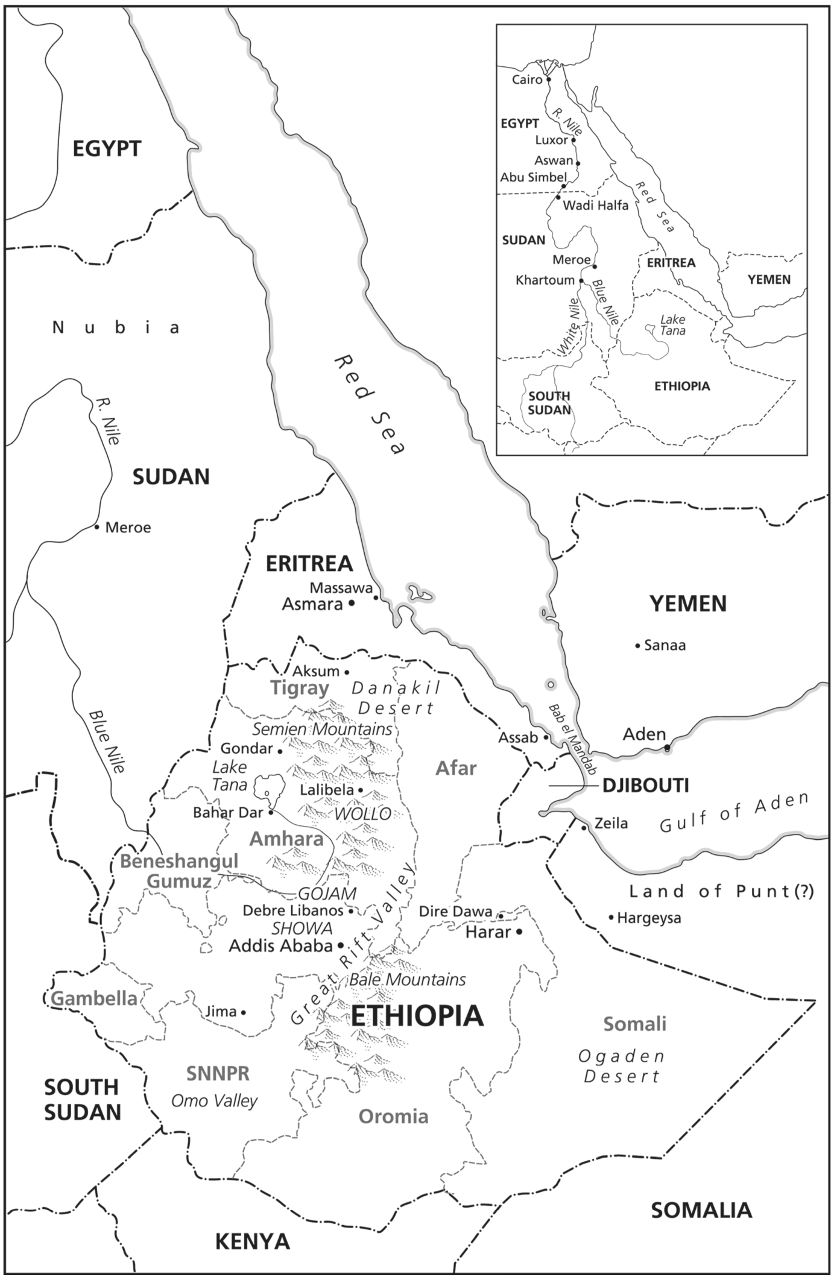

Today, we may be sure Ethiopia is a country in north-east Africa, but the countrys borders have not always been so well defined. Depending on the whims and knowledge of writers and geographers, Ethiopia was at times made up of all of sub-Saharan Africa with a coastline that wandered from the Red Sea to the Atlantic Ocean or was solely the area circumscribed between the northern reach of Egypts desert, the confluence of the Blue and White Niles and the Atbara river. In a later incarnation, the country became a saintly empire administered by an anointed priest-king, known as Prester John: an empire so munificent and kaleidoscopic that it was found in the Congo, in Mongolia, in Syria and, finally, in the Christian kingdom of the hinterlands of the Red Sea. The Greek Bible had the spawn of Shem, Kush and Ham go and multiply in Egypt and Aethiopia a tale later reprised in a legend that has Axums first capital founded by none other than Ityopis, son of Kush. Later the Ethiopian Queen Kandaces eunuch is converted by the Apostle Philip on the road to Damascus and returns to convert queen and kingdom to Christianity. Research has revealed that biblical transcribers and interpreters had rendered Kandace from the Meroitic for Queen or Queen Mother. This title, in various guises and local languages, was used until the twentieth century to denote the Ethiopian queen.

It is this intertexual play carried out on a minds eye map, which is so fascinating to the amateur Ethiopianist, and to the visitor to Ethiopia. No country can be better grasped from the depths of an armchair, and a library is as good a place as any to make out the ancient contours of the land of Prester John, Mandeville and Rasselas, as well as the new outlines of a country that today is attempting with great vigour to shake off the modern myth it was saddled with of Korem and the 1970s famine, of the Dergs Red Terror, and of poverty and refugee camps. The BBCs John Buerk and Jonathan Dimblebys pronouncements on Ethiopia have had as much, if not more, resonance in the modern era as all of the Classical and Enlightenment authors put together. And yet when John Buerk began his famous intervention at dawn in Korem, he too harked back to the text and the myth, when he intoned on camera those now famous words: Dawn, and as the sun breaks through the piercing chill of night on the plain outside Korem, it lights up a biblical famine, now, in the twentieth century.

One could be forgiven for thinking that these references are so many worn-out palimpsests now lying unused by the young, and certainly never used by Ethiopians themselves. But one would be wrong. For however bland and annoying those references to biblical imagery may seem to be the epithet biblical is etched on the land itself. For a country that has so many illiterates, the Ethiopians own knowledge of historical works, myths, and books referencing their country is quite astounding. As is their respect for the word, for rhetoric and their love of poetry. Since time immemorial, magic scrolls, consisting in wide-eyed angel sketches and verses from the Psalms of David, have been worn tightly rolled up in cartouches around necks to ward off the evil eye. And it is said that Emperor Zera Yacob (13991468) himself a scholar who penned various religious treatises so much believed in the power of the word that he promulgated that all his subjects should have I renounce Satan tattooed on their wrists.