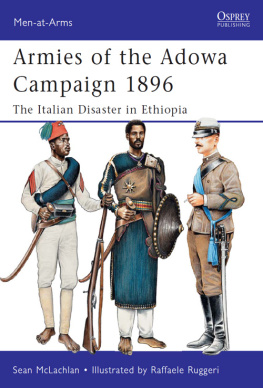

Men-at-Arms 471

Armies of the Adowa Campaign 1896

The Italian Disaster in Ethiopia

Sean McLachlan Illustrated by Raffaele Ruggeri

Series editor Martin Windrow

CONTENTS

ARMIES OF THE ADOWA CAMPAIGN 1896

ITALYS EAST AFRICAN AMBITIONS

I n the late 19th century, Italy was one of the youngest of the European nations. It had only been politically unified under the northern throne of Savoy by force of arms in 1861, and in human terms this unity was a fiction. Governments anxious to create a true sense of nationhood sought foreign quarrels, in the hope that war any war would unite Italians psychologically. Naturally, Italy lagged far behind in the race for colonies, and older and stronger powers such as Britain, France and Spain had already staked claims over much of the non-European world. One of the few remaining regions where Italy might prove itself by gaining colonies of its own was north-east Africa, on the western shore of the Red Sea.

A striking portrait of an Eritrean ascaro, in this case identified by the badge and light blue tassel on his tarbush or fez as serving with the Carabinieri paramilitary police established in the colony. His aspect is typical of fighting men in this part of north-east Africa, whose warrior tradition is undimmed today; the ascari proved themselves notably steady under fire. Generally the relationships between Italian officers and their African troops were reported to be good, once new arrivals from Italy had learned the folly of any prejudiced assumptions. There were numerous accounts of ascari protecting their officers to the death. (Courtesy Stato Maggiore dellEsercito, Ufficio Storico hereafter, SME/US)

While the French had established a foothold at what is now Djibouti, and the British were expanding their colony in present-day Kenya and Uganda, a large region remained uncolonized Abyssinia, today known as Ethiopia and Eritrea. This vast territory included high, arid mountains and fertile valleys, as well as peripheral regions of desert and savannah. A patchwork of different tribes inhabited these territories, ruled by a complex aristocratic hierarchy, and to a great extent following an idiosyncratic version of Christianity. Over all was the nominal ruler of the entire country the Negus Negasti or king of kings. Some of these emperors had managed to unify the country for a short time, but under weaker central rulers Abyssinia was a conglomeration of feudal warlord fiefdoms, and this potentially rich but divided land attracted the ambitions of the Italians.

In 1869 the Suez Canal was opcened, thus greatly increasing the importance of the Red Sea for the shipping of the far-flung British and French empires. That same year an Italian firm established a coaling station on land bought from a local ruler in Assab Bay, in the narrows of the Gulf of Aden. In 1883 they sold it to the Italian government, which began expanding it into a colony. In 1885, taking advantage of Britains and Egypts distraction by the Mahdis warlike followers in the Sudan (the so-called Dervishes), Italy took possession of the nearby port of Beilul. In the same year the Italians also landed some 250 miles north-westwards up the Red Sea coast and occupied Massawa one of the most important harbours in the whole region. The Egyptians who had previously claimed it could do little but complain about this landing; their own garrisons would have been unable to hold out against the Mahdi, and Britain approved the transfer of power.

During the following year, Italy spread out along 650 miles of coastline, from Cape Kasar in the north to the French enclave of Obok (modern Djibouti) in the south; this corresponds almost exactly to the coast of modern Eritrea. The British actually encouraged Italian expansion in the Red Sea as a way to offset potential French influence. (While Britain had sent an expedition into Ethiopia in 1868 to defeat the Emperor Tewedros and save his European hostages, they had no interest in actually colonizing the country.)

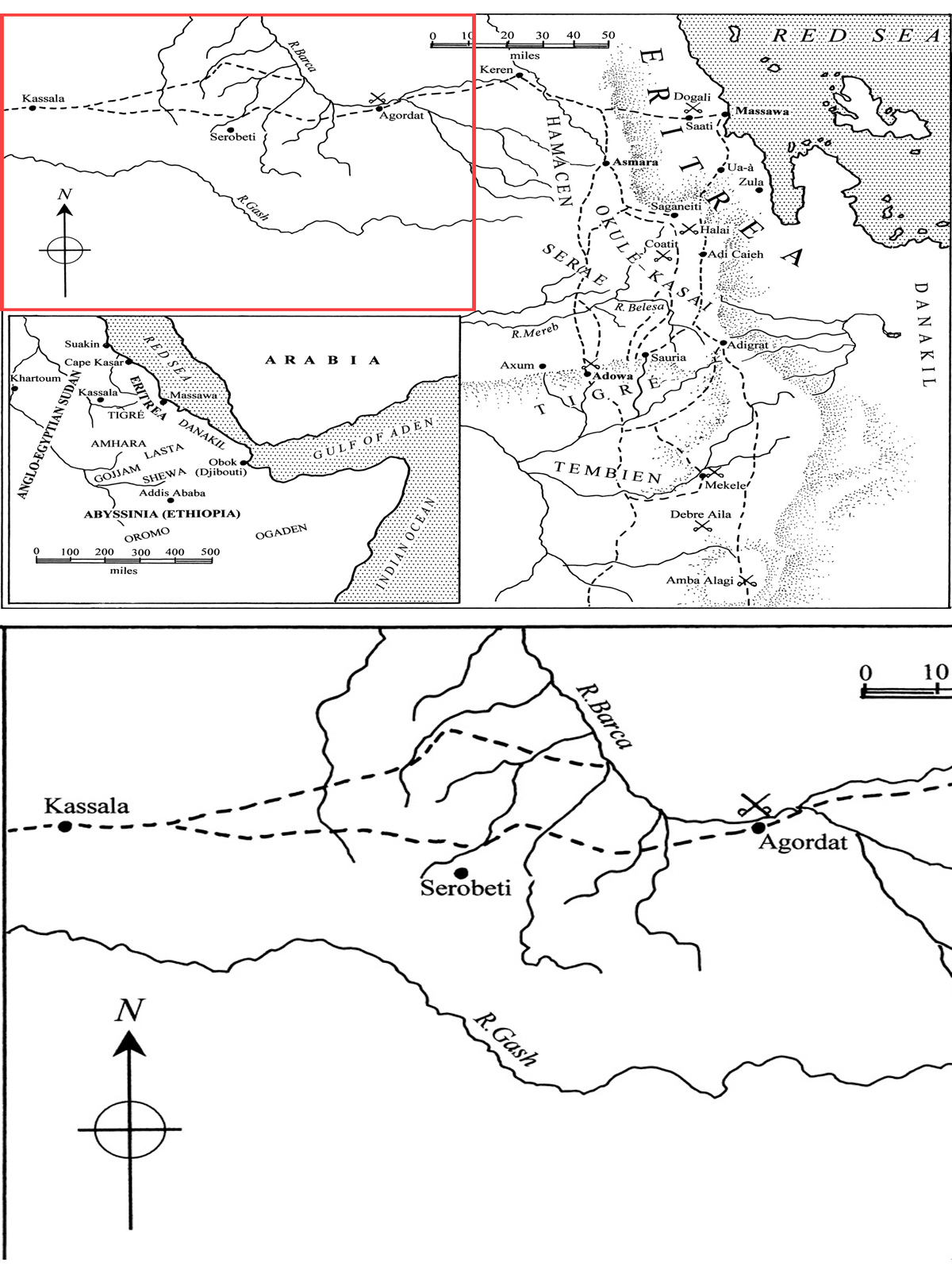

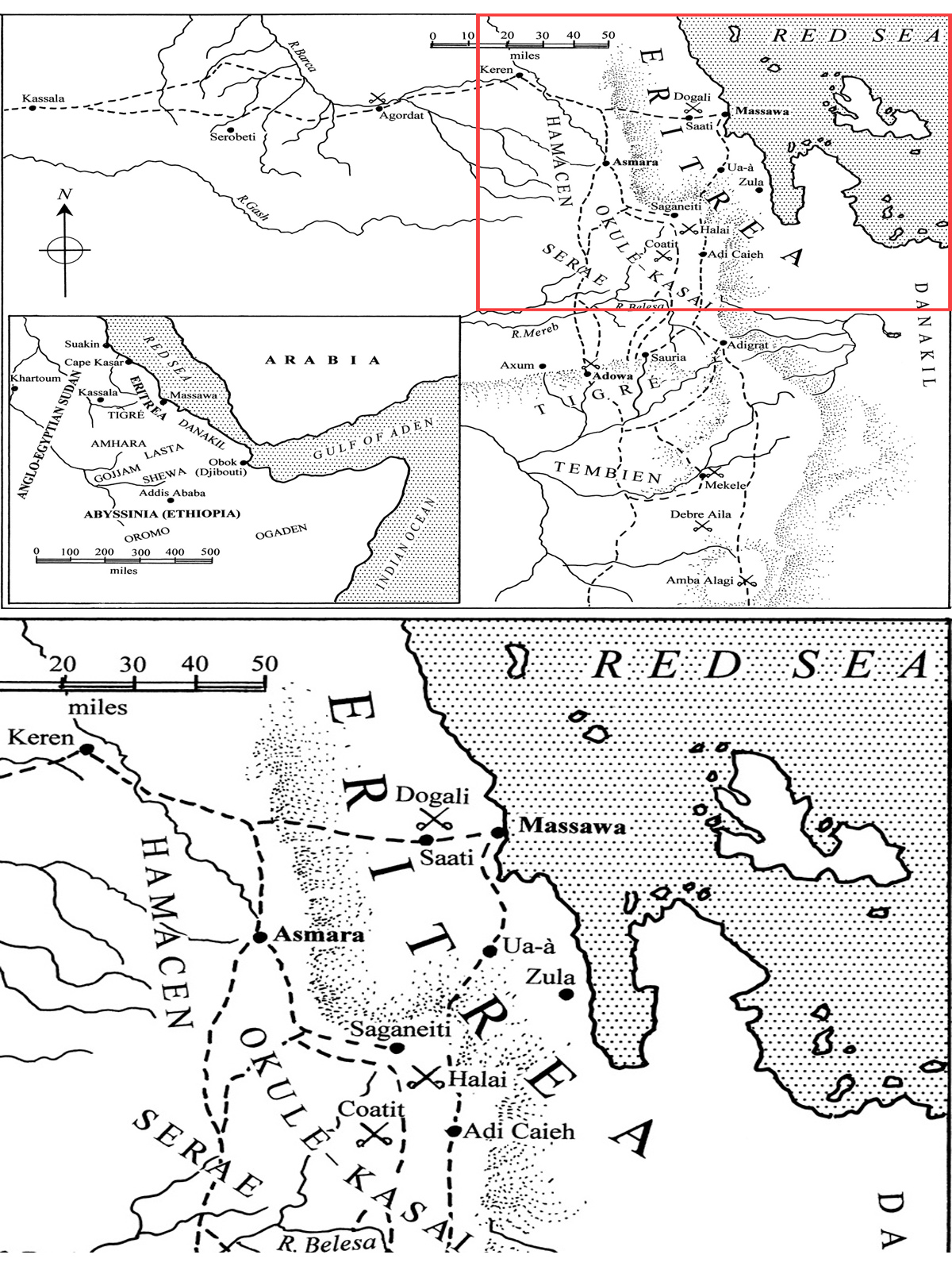

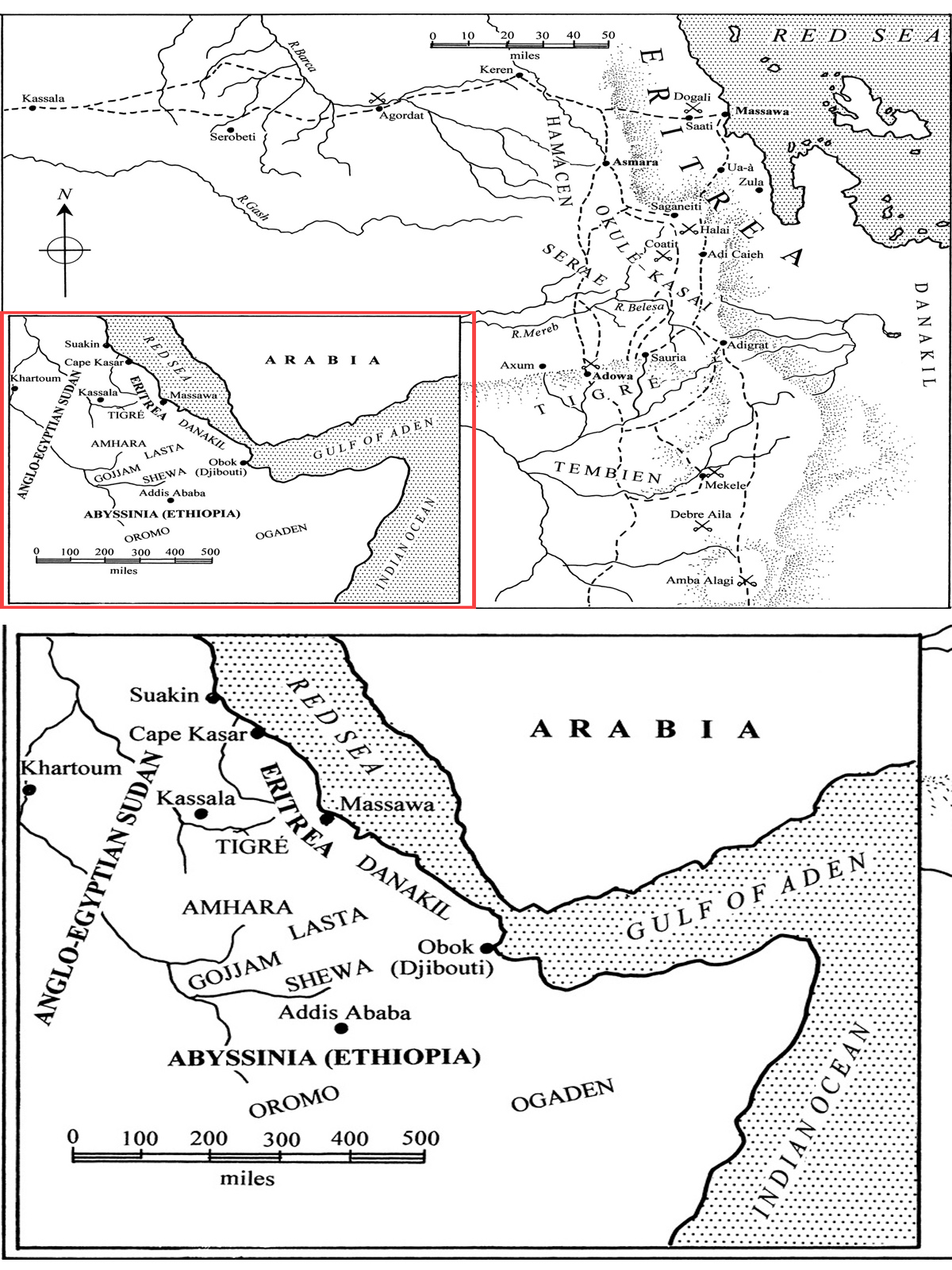

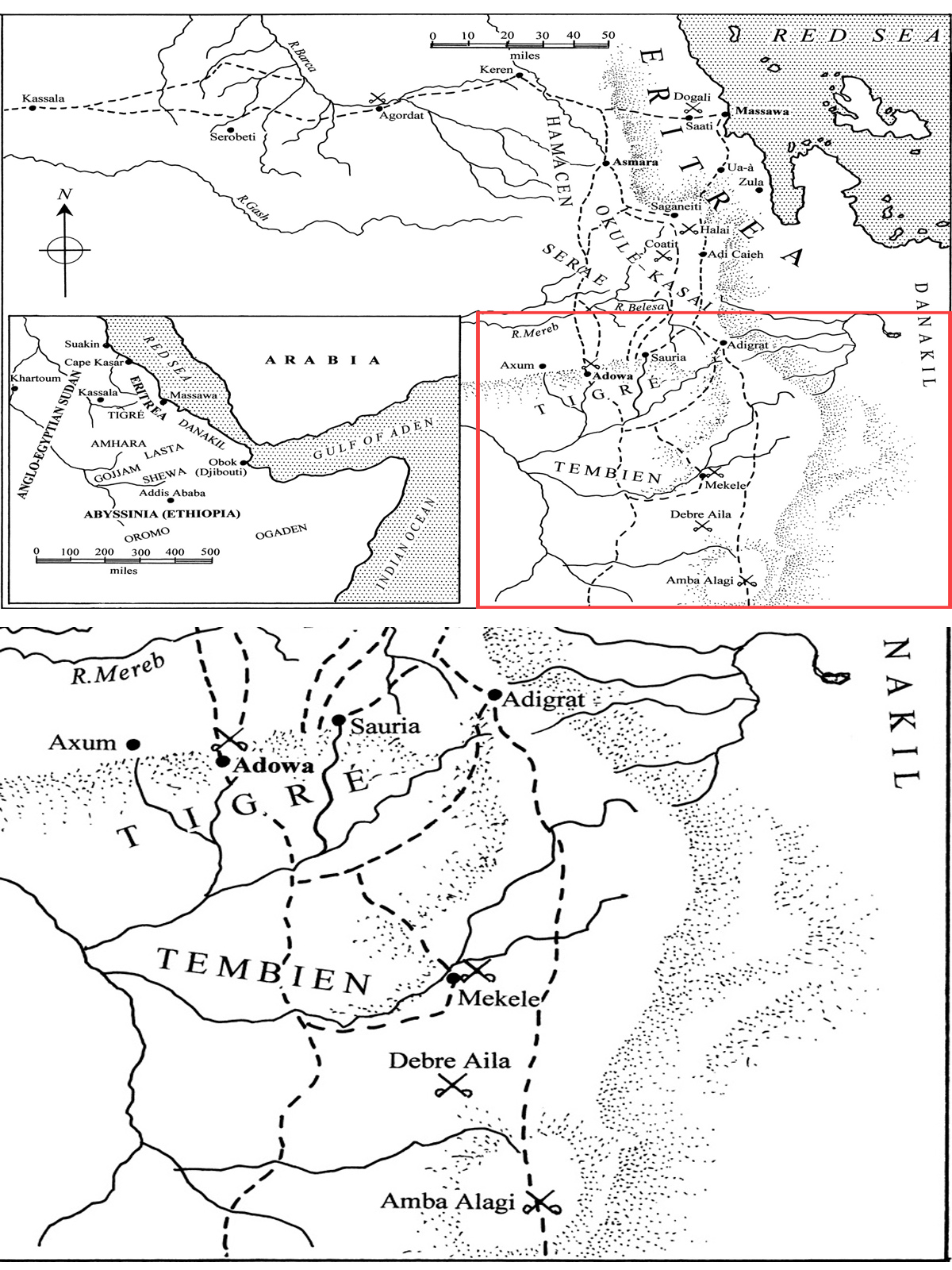

The Mahdist and Ethiopian campaigns, 188596; broken lines indicate main Italian lines of communication, and shading shows the approximate edges of the highlands. The provinces of Hamacen, Okule-Kasai and Serae were all historically subject to the rulers of the Tigr region of northern Abyssinia. (Inset) General map of the region. (Maps by John Richards)

Defeat at Dogali, 1887

The Emperor Yohannes IV of Ethiopia resented being cut off from the sea by this new Italian incursion. Tensions arose, especially in 1887, when the Italians decided to strengthen their position by pushing inland and taking over the villages of Ua- and Zula. The local lord, Ras Alula, demanded that the Italians leave, and when they failed to do so he gathered 25,000 warriors. On 25 January 1887 he attacked the fort at Saati, held by 167 Italians and 1,000 native troops, but found it too strong to take. He had better luck the next day, when he attacked a relief column heading for the fort. Led by LtCol De Cristoforis, this force consisted of 500 Italians, 50 native irregulars, and two machine guns. Ras Alula ambushed them at Dogali with about 10,000 warriors; the Italian machine guns soon jammed, and the relief force was surrounded and cut down. The Italians lost 23 officers and 407 men killed, one officer and 81 men wounded. The Italians estimated that Ras Alula lost 1,000 warriors at the battle of Dogali, although this is debatable. The Italians quickly vacated the contested villages, as well as the fort at Saati.

This defeat led to a massive Italian reinforcement of what would become their colony of Eritrea. By the end of 1887 troops in the colony numbered 18,000, of whom only 2,000 were natives, and an arms embargo on Ethiopia was in place. The military governor, Gen Di San Marzano, fortified Massawa, retook the inland villages and fort, and began building more forts on the border and at key internal sites. He also started building a railway from Massawa to Saati, to exploit the regions mineral wealth.

By the end of March 1888, the Emperor Yohannes and Ras Alula were negotiating peace with the Italians. The colony continued to strengthen and expand, and in October 1888 the first units of ascari were formed. These native battalions were mostly drawn from the Eritrean population, along with Sudanese gunners, and they replaced the irregular Turkish and local mercenaries that the Italians had previously employed.

The Italians next challenge came from the loosely structured Mahdiyya army in the Sudan. The Mahdi claimed to be the new prophet of Islam, and his devout followers drawn from disparate peoples made great gains against the British-sponsored Egyptians and neighbouring tribes. There had been a longstanding rivalry between these Muslim warriors and the mostly Christian Ethiopians. Emperor Yohannes campaigned against the Dervishes, but, while at first successful, he was defeated and fatally wounded at the battle of Metemma on 9 March 1889. The Italians took advantage of Yohannes absence on campaign to push further inland, taking the Tigran provinces of Hamacen, Okule-Kasai, and Serae; these would become the principal territories of the future colony, and modern nation, of Eritrea.