Contents

Landmarks

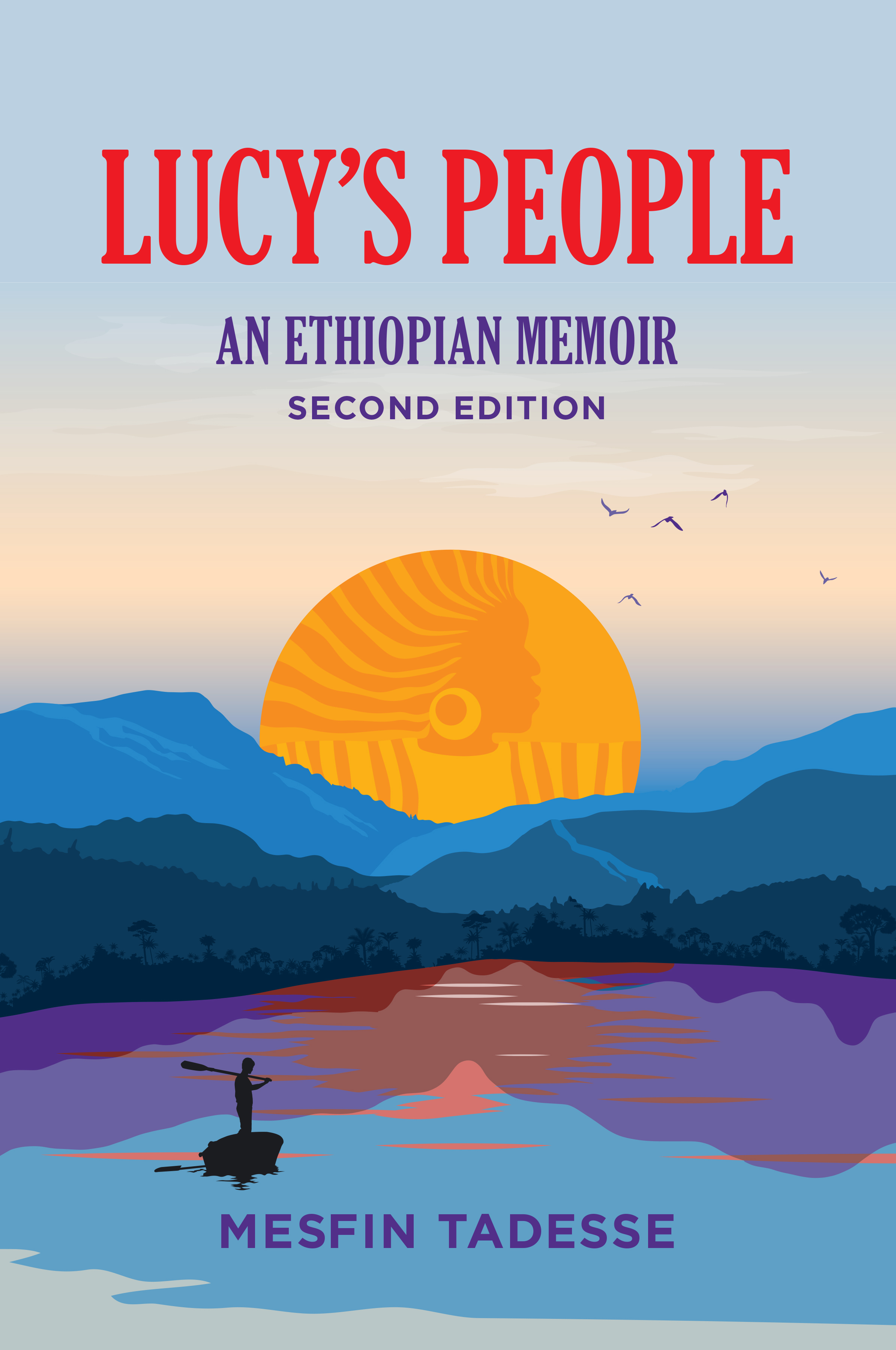

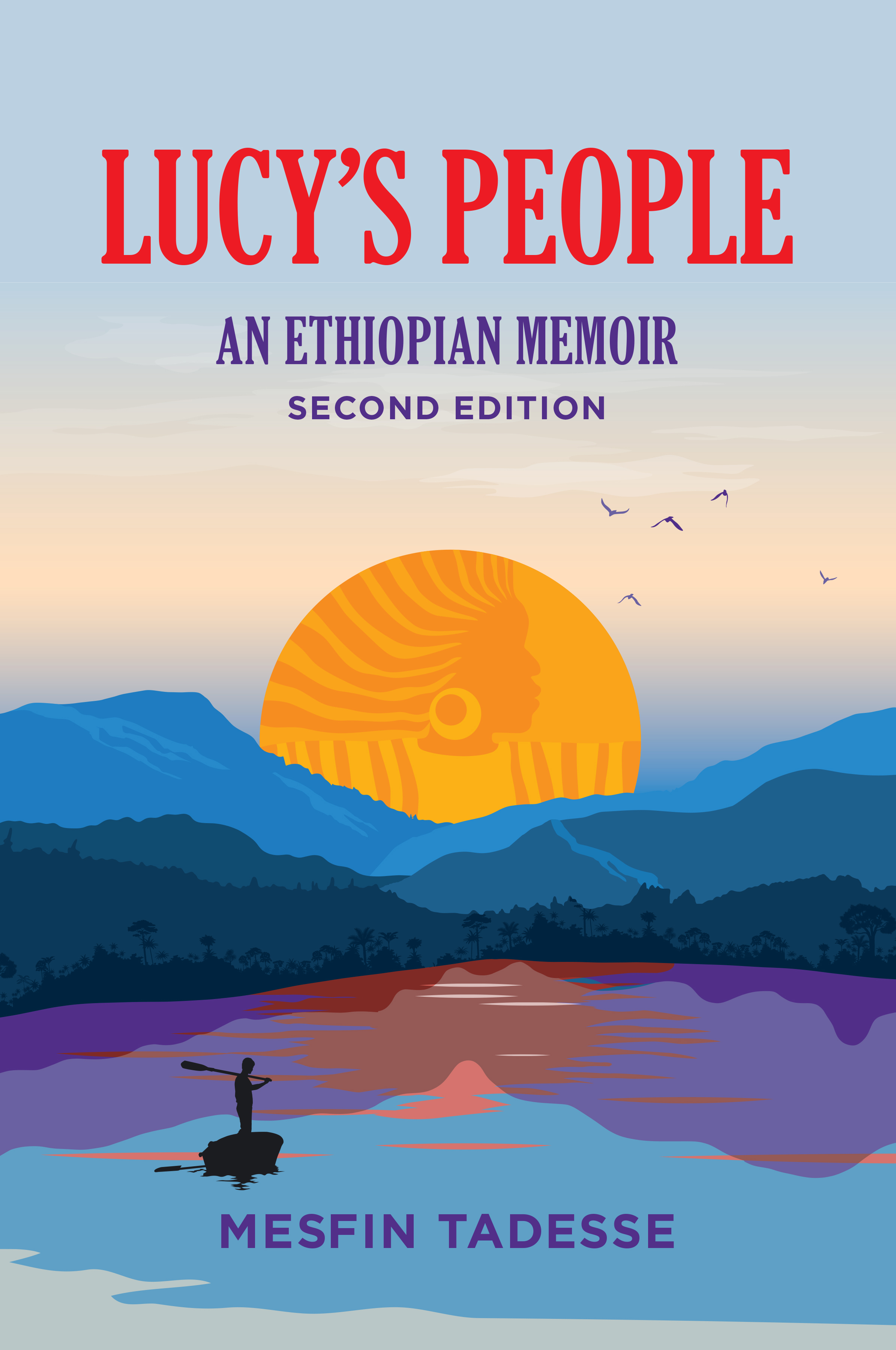

Lucys People: An Ethiopian Memoir

Second edition

Paperback ISBN 978-0-6488287-2-3

eBook ISBN 978-0-6488287-1-6

2021 Mesfin Tadesse & Ianet Bastyan

Published by Yerada Lij Australia

Wilson, Western Australia

www.yeradalij.ink/

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted. All rights reserved. Reproduction, transmission and adaptation of any part is not permitted. Fair Dealing permitted. For enquiries, email the publisher.

Editor & publishing consultant: Sam Cooney

Designer: Tess McCabe

Cover images from iStockphoto.com

For Tewode and Samual

When they pried his fingers open,

this nobody,

they found a whole country.

Hama Tuma, Just a Nobody

T oday in Australia, an Indian immigrant waits at the airport taxi rank. An Aussie raps knuckles on his cab window.

You Ethiopian?

No.

The customer gets in. If he had said, Yes, the man would have moved on down the queue. The driver wonders why some customers avoid Ethiopians. What if they think he is one? Riled, they might do anything.

He visits the local library to read up on Ethiopia. Staff say, Nothing much is available in English.

It is the same at the State Library. The driver resorts to the internet. He finds out about the Battle of Adwa 1896, led by Emperor Menelik II. Inspired by Ethiopias triumph over Italian invaders, he phones his pregnant wife in India.

She says, Our child will be named Menelik, boy or girl.

The driver displays Meneliks photo in the back window of his taxi. He sports a Menelik beard and hat. Aussies admire it. He says, This style originally belonged to Emperor Menelik II of Ethiopia.

One day he leans over the fence of his rental and says to his neighbour, The hens in your backyard remind me of home. I asked the landlord to install a wire mesh dividing fence this one needs replacing. She refused.

They introduce themselves. The neighbours name is Mesfin. He also wears a Menelik-style hat and is Ethiopian.

Mesfin was born during the reign of Emperor Haile Selassie I. With millions of others, he suffered under the brutal communist Derg. A fine engineer, he gave all to family and motherland. Then came a change of government in 1991. Mesfin had to choose: stay or flee?

Lucys People is his memoir. It is for readers ready to accept a ride with one of the greatest cultures on earth.

Ianet

People ask, Is this story true? It is, so to protect privacy we use first names or no personal names. Addressing Ethiopians by their first name is polite. Mr, Teacher or Chief might come before it. We use full names for prominent people.

Lucys People has Ethiopian words. We like their flavour and rich meaning. There are about 85 Ethiopian languages. Mesfin uses Amharic, Geez and Hebrew. Ethiopians speak Amharic, the national language, and home languages. Geez is classical Ethiopian. Many Ethiopian Jews speak Hebrew.

Dates in this book follow the Gregorian calendar of the West. It is seven or eight years ahead of Ethiopias. For example, early 1991 was 1983 in Ethiopia.

In 2020, we released the first edition of Lucys People in Addis Ababa. Then the Australian Government stranded us in Ethiopia due to COVID-19. Much happened there and we re-worked our book. is re-arranged. We corrected dates and added details. More Derg jokes crept in while we inserted notes and a bibliography. The story is the same.

Mesfin & Ianet

T en soldiers shouldered and levelled AK-47s and Kalashnikovs. Cadre frowned at the site plan. I inverted my drawing. Other way.

mumbo jumbo

The party members nodded. Go ahead. I escaped their praise of the communist president, all lifil lifil.

My boss chased me with my risk reduction report. Alemayehu had said, Let me handle this. He removed my references to Chernobyl. The facts remained, all 27 pages. Reinforced concrete was magnetic. Radiation melted zinc alum. Basaltic stone sparked: it contained cast iron with carbon from coal. Construction had to be with reinforced concrete containing pure metal.

The civil engineer ruffled my hair. Order Portland cement with hydrated lime river sand. We were still within gunsights. Two workers together had a time limit of three minutes. In the dining room, cadre separated us by 1.5 metres. If three spoke they were dead. I left to buy construction materials.

Water expanses were my love: weirs, dams and irrigation. Ethiopias only employer was the Planning and Labour Commission. It stuck me at the Gouder Tank and Missile Factory. Party insiders kept me underground in one zone for two years.

I was building the yellowcake silo water system and the chemical waste and nuclear waste treatment plants. Silo walls had to resist concrete bunker missiles, floods, landslides and earthquakes. What would happen in a catastrophe? In one nuclear explosion, half of Addis Ababa would go.

The next morning, government forces rounded up 47 technicians and engineers. We were aged between 17 and 32. They said we were from Western influenced worksites. The squad detained us without charge. They took us 180 kilometres north, outside the city. We were ravenous and thirsty.

At 2.30 a.m. soldiers bound us severely with ropes. They threw us into a truck and drove for 25 minutes to the forest beyond Gulele outside Addis Ababa. Five men died of asphyxiation.

automatic rifles

A jeep with rocket-propelled grenades stopped us. It was impossible to run. Guards had chichi, twice the size of Kalashnikovs, and AK-47s. One climbed into a waiting bulldozer and started the engine. Get on with it. Shower them.

Prisoners cried, but a debate began among soldiers.

This is wrong, Major. They have done nothing. Let our sons and brothers go.

Colonel, what about our careers? We will be at risk if word gets out that we have disobeyed orders.

Not if you keep quiet about it. Finish digging the trench. Make it look real.

The major relented after 20 minutes. The colonel called the army nurse. Verify that those five are dead.

The recruit had never seen a dead goat, let alone a human corpse. I do not know how. It is too dark.

Hold your torch. Use a mirror. If there is mist on the glass, he is alive. Stop crying and be a man. The nurse, major and colonel laid the five bodies in the trench dug for show.

They yelled to the remaining 42 of us, Run for your lives!

Here is ten birr.

Take my watch.

Go! Live.

We fled until sunrise, lost. All reeked of the urine and excrement of the dying or terrified piled in the truck. An engineer from the country said, Keep out of the eucalyptus plantation. Guards will shoot.

under wing

Oromo farmers found us. The mothers gave us bibit shelter. They muddied us to hide city skin, dressed us in their clothes, took us out at night. Too poor to eat meat themselves, they slaughtered chickens and goats to feed the thin ones among us. Many Ethiopians born between 1950 and 1975 experienced how Oromo people treated fugitives as though they were their own.

Oromo people were the largest Ethiopian group. The national language was Amharic. As they combed our hair, I worked out what they said in Orominya: His mother must be good. He has no lice.

After three months, the communists lost interest in their campaign against the educated. We returned home. In Arat Kilo, my girlfriend Hewan had slept on the floor. She lit church candles, for whom she would not say. Barely expecting to reach 30, we married.

Next page