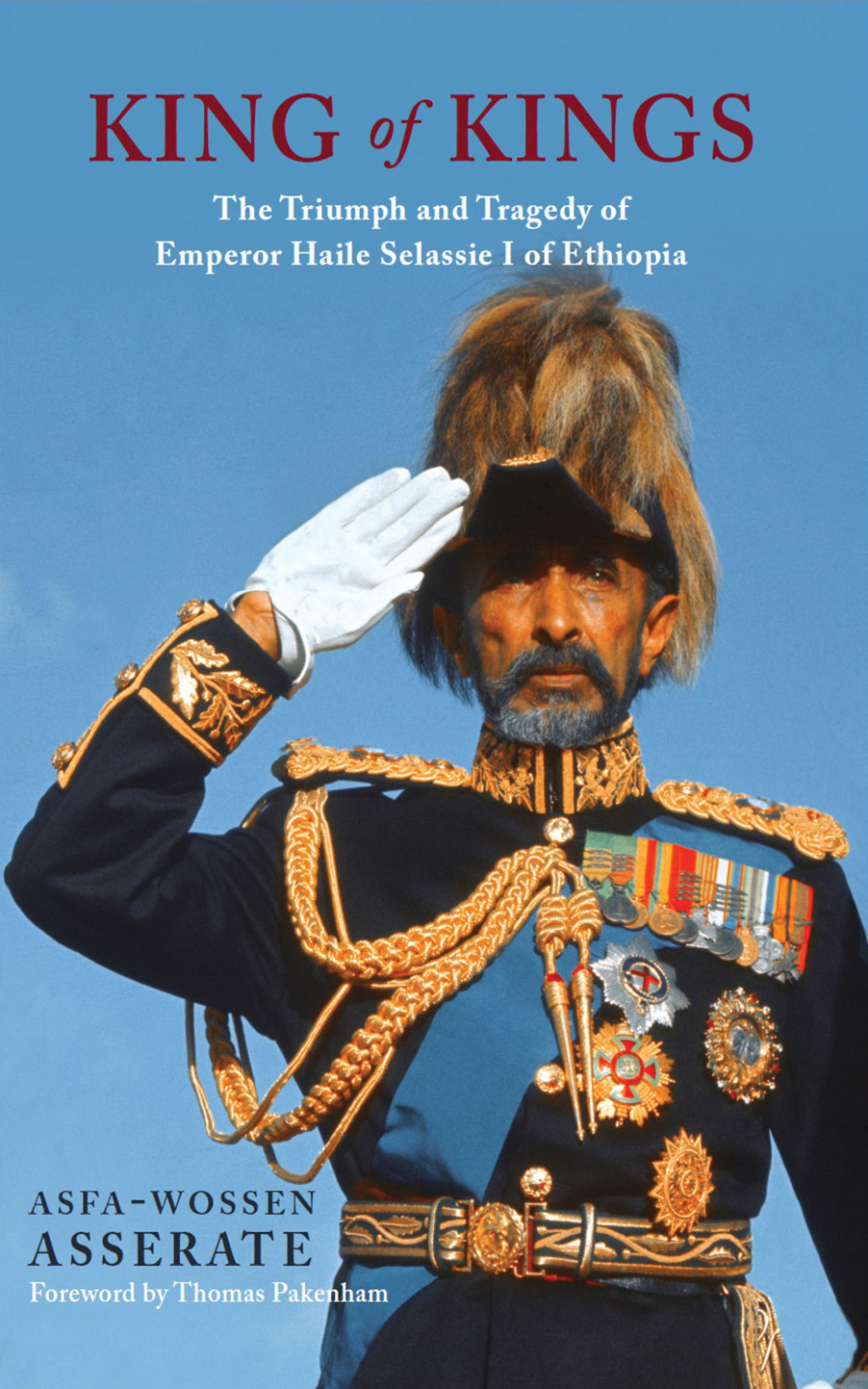

KING OF KINGS

The Triumph and Tragedy of

Emperor Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia

Asfa-Wossen Asserate

Translated by Peter Lewis

Foreword by Thomas Pakenham

First published in English in 2015 by

HAUS PUBLISHING LTD

70 Cadogan Place

London SW1X 9AH

www.hauspublishing.com

Originally published in German as Der Letzte Kaiser von Afrika: Triumph und Tragdie des Haile Selassie by Asfa-Wossen Asserte by Ullstein Buchverlage GmbH, Berlin.

Published in 2014 by Propylen Verlag

Translation Copyright 2015 by Peter Lewis

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-910376-14-0

eISBN: 978-1-910376-19-5

All rights reserved.

Contents

This book is dedicated to my maternal great-grandmother and the caring Mother of All Ethiopians,

H.I.M. Empress Menen Asfaw, with great admiration and heartfelt devotion.

Asfa-Wossen Asserate

Foreword

By Thomas Pakenham

For many years there was a missing piece at the centre of the jigsaw of African history. There was no full-scale biography of the Emperor Haile Selassie. Yet no other African ruler had kept his grip on power for so many decades. Regent from 1916 to 1930, Emperor from 1930 to 1974, he excited the admiration of African leaders of later generations even those who had come to power by democratic means. To many of his own subjects in Ethiopia he seemed almost like a god. To the Rastafarians of Jamaica he was the Messiah. Yet when he finally fell from power, and was secretly killed by the Derg, the revolutionary junta, he seemed already like a ghost from the past.

Now Asfa-Wossen Asserate has gallantly risen to the challenge. This is an insiders account, based on many personal sources not available to other historians. He has exploited a unique advantage: the history of his own family was, for three generations, interwoven with the history of the emperor. His paternal grandfather, Ras Kassa, was one of the five leading Ethiopian nobles who had chosen Ras Tafari (as the future emperor was then styled) to become regent after the overthrow of Emperor Lij Iyasu. In fact Ras Kassa was Tafaris cousin and had a better dynastic claim to the throne than Tafari, as his family was descended not only from the Shoan branch of the Solomonic line, which had ruled Ethiopia since 1889, but also from the Imperial Gondarine-Lasta line, which had ruled the country in previous centuries. But neither Ras Kassa nor Asfa-Wossens father, Ras Asserate, had the appetite for imperial power. Both men remained stubbornly loyal to the emperor by contrast with most of the other feudal nobles. Yet the loyalty of Ras Asserate, as his son poignantly describes, was tested almost to breaking point in the final years of the Haile Selassies reign.

Asfa-Wossen begins his story in the declining years of the Emperor Menelik. Ras Tafaris father, Ras Makonnen, was one of Meneliks most loyal and most accomplished generals. After helping to defeat the Italians at the Battle of Adwa in 1896, Makonnen was given control of the south-eastern province of Harar, and it was here that the future emperor spent his boyhood and was educated by Europeans. However, the early death of his father catapulted Tafari forward into the dynastic struggle. At thirteen he was already the titular governor of Salale; at eighteen he assumed control of Harar, his fathers old province; at twenty-four he was regent and effectively in control of the country. Already he had had to crush a revolt by Lij Iyasu, Meneliks wayward grandson, who had been the first heir apparent but was deposed on the pretext he had converted to Islam. (The charge was probably false, but Lij Iyasu was placed under house arrest, watched over by Ras Kassa, Asfa-Wossens grandfather.) There was nothing wayward about Tafari. Although slightly built and a head shorter than most Ethiopian nobles, he seemed every inch the man of destiny. He preferred to out-manoeuvre his enemies rather than to crush them, and had a genius for playing off one faction against another. But when directly challenged he could be ruthless enough. After his rival Lij Iyasu escaped from Ras Kassas care, Lij Iyasu was re-captured and chained to a post, then mysteriously killed in 1935 perhaps on the emperors orders.

By 1920 Haile Selassie had taken the first steps to modernise the country. He built schools and hospitals and invited Europeans to staff them. There was even a nod in the direction of democracy: promise of a parliament, a senate and a written constitution. In fact he had created an absolute monarchy for himself and his family. But there was one enemy it was not in his power to subdue: Mussolinis Italy. Smarting over their defeat at Adwa forty years earlier, the Fascist armies pushed south into Ethiopia from their colonial base in Eritrea on the Red Sea. By 1936, their motorised columns had smashed the ill-equipped Ethiopian warriors, and the emperor (accompanied by Asfa-Wossens father and grandfather) was a fugitive in England. For most Ethiopians the war was a catastrophe. (Three of Ras Kassas sons, fighting with the partisans, had surrendered on the promise of safe conduct and were then shot by the Italians.) But for the emperor this was in a way his finest hour. Out of the humiliation of defeat he had created an astonishing moral victory. He was the first (and last) African ruler to address the League of Nations. He denounced the barbarism of the Italian invasion. And if the world could do little to help him, at least it had ears to listen and in general to agree.

Five years later, in 1941, the Emperor was back in power, put back on his throne by British and South African forces. And for the next nineteen years, still playing off one opponent against another and depriving the aristocrats of their private armies, he ruled the country unchallenged. For two terms he chaired the Organisation for African Unity and earned much admiration from his fellow rulers. But back in Ethiopia the pace of reform seemed agonisingly slow, especially to the growing number of Ethiopians educated abroad. Of course this was the price of absolute monarchy: an absolute bottleneck. Press, Parliament and cabinet remained puppets in the hands of the emperor. And then, in 1960, the emperors throne was shaken by a first political earthquake.

It is from this point that Asfa-Wossen, who was twelve years old in 1960, can speak as an eyewitness. His father, Asserate Kassa, was the leading loyalist who rallied the country against an attempted coup by two of the commanders of the emperors bodyguard. The plan was to depose the emperor, while he was absent on a state visit to Brazil, and replace him with his son, the Crown Prince, appointed as a constitutional monarch. To many peoples surprise, the Crown Prince played his part, and broadcast to the nation the news that he had replaced his father. (Asfa-Wossen cites evidence that the Crown Prince made this broadcast freely enough, although the official version, published later, claimed that he spoke with a gun in his back.) But the coup was botched. The main army, the students, the urban public, the landless peasants they had no shortage of grievances. But who wanted to throw in their lot with the emperors bodyguard? The coup ended in a massacre of senior ministers at the palace, which Asserate was lucky to escape. This was followed by the pursuit and suicide of two of the leading conspirators. Others were hunted down and publicly hanged.