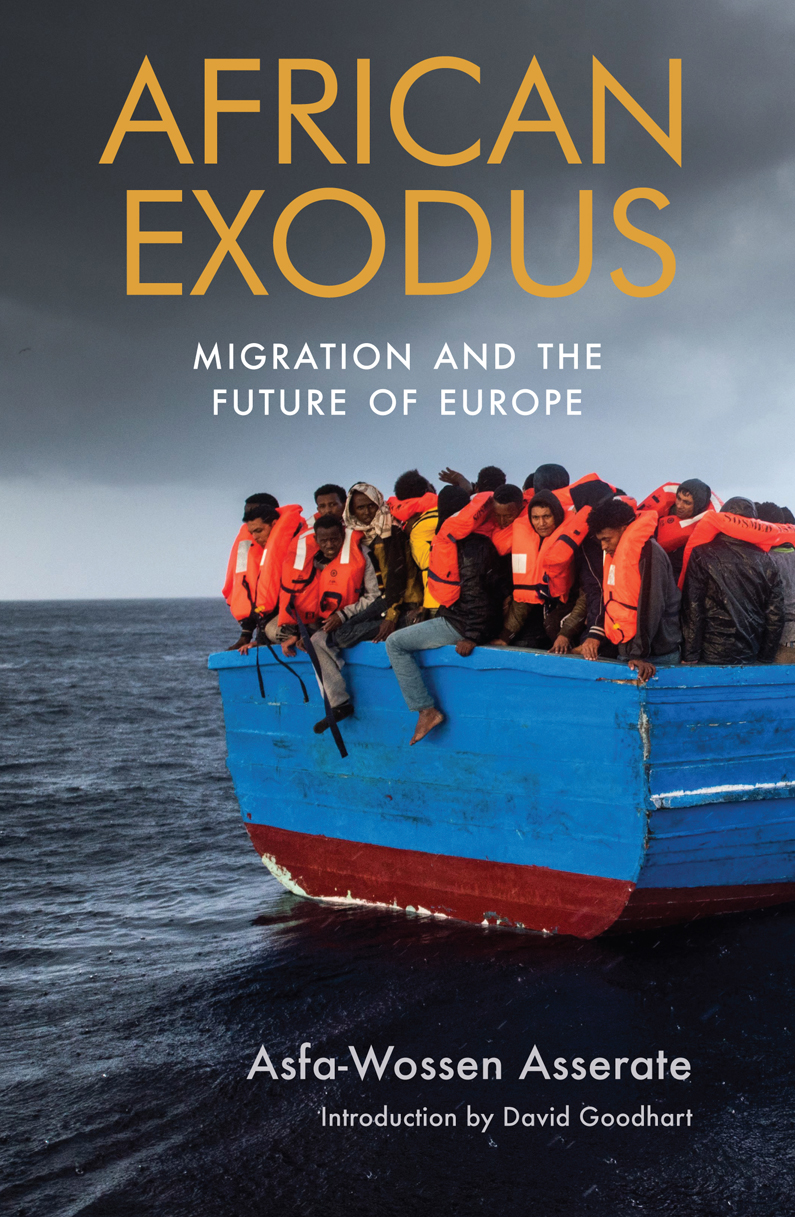

Asfa-Wossen Asserate - African Exodus: Migration and the Future of Europe

Here you can read online Asfa-Wossen Asserate - African Exodus: Migration and the Future of Europe full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2018, publisher: Haus Publishing, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:African Exodus: Migration and the Future of Europe

- Author:

- Publisher:Haus Publishing

- Genre:

- Year:2018

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

African Exodus: Migration and the Future of Europe: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "African Exodus: Migration and the Future of Europe" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

African Exodus: Migration and the Future of Europe — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "African Exodus: Migration and the Future of Europe" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

AFRICAN EXODUS

AFRICAN EXODUS

Migration and the Future of Europe

Asfa-Wossen Asserate

Translated by Peter Lewis

Introduction by David Goodhart

Published in 2018 by

HAUS PUBLISHING LTD

70 Cadogan Place

London swix 9AH

Originally published in German as Die neue Vlkerwanderung: Wer

Europa bewahren will, muss Afrika retten by Asfa-Wossen Asserate

by Ullstein Buchverlage GmbH, Berlin. Published in 2016 by Propylen Verlag

Translation Copyright 2018 by Peter Lewis

Introduction Copyright 2018 by David Goodhart

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-910376-90-4

eISBN: 978-1-910376-91-1

Typeset in Garamond by MacGuru Ltd

Printed in Spain

All rights reserved.

No one leaves home unless home is the mouth of a shark

Warsan Shire, Home

To the millions of African refugees dispersed across all continents who have been forced to swallow the bitter pill of exile, I dedicate this book in solidarity and in the fervent hope that their martyrdom may soon end.

Asfa-Wossen Asserate

PROLOGUE

I was a refugee too

I was once a refugee as well; I too have my personal tale of flight. While the revolution took its course in my homeland during the spring and summer of 1974, bringing about the downfall of the Empire of Ethiopia, I was a student in the German city of Frankfurt am Main. From my small student flat, I listened to the radio to follow the events in my home country, which also engulfed my family. First, my father, Prince Asserate Kassa, a leading politician of the empire, was detained by the military junta that now regarded itself as the new government of Ethiopia. Shortly afterwards, my mother and my siblings found themselves in the firing line, as the military took them into custody too. On 24 November 1974 there came a radio report that more than 60 leading politicians of the imperial government had been murdered in Addis Ababa one of them was my father. No charges had ever been brought against him, nor had he been brought to trial. Like the others, he had simply been taken from the gaol under cover of darkness and summarily executed by firing squad. The atrocity went down in history as Ethiopias Bloody Saturday.

What this meant for me took some time to sink in. My father was dead. My mother and my siblings were incarcerated without charge but at least they were still alive. I was the only member of our family who was living freely and safely. A few months later my Ethiopian passport expired. I arranged a meeting at the Ethiopian embassy in Bonn. The ambassador, whom I knew personally, was astonished that I should still be in possession of my passport. He took a few hours to consult with Addis Ababa. Then he announced that a new Ethiopian passport could not be issued to me because of my counterrevolutionary activities. At a stroke, I had become a stateless person.

The following day I applied for asylum in Frankfurt in those days this was still a very rare occurrence for an Ethiopian. Normally, one would have been required to present oneself in person to the so-called Federal Department for the Recognition of Foreign Refugees, which was located in a small town in Middle Franconia called Zirndorf, but in my case, a decision was reached on the basis of my personal records. It took no more than a week for me to receive a notification that my claim had been accepted, along with a foreigners travel document that guaranteed me the right of abode and the right to work in Germany for the next seven years.

Those who are being persecuted politically have the right to asylum, stipulated Article 16 of the German constitution. I was a textbook case of a political refugee but judging by todays standards I was far from being a typical refugee. I had not had to use the services of a people-trafficker, paying through the nose to do so. I had not had to travel for days on end through the desert with a backpack containing all my worldly possessions, driven on by the fear of being discovered by the military or the police. I had not had to spend months languishing in a detention camp, stigmatised as an illegal alien and hoping that I might somehow, someday, be allowed to continue my onward journey. I had not had to make a perilous sea voyage crammed together with hundreds of others in an unseaworthy rubber dinghy. I had not been locked into the pitch-black trailer of a lorry, fearful of whether the doors would ever be opened again while I was still alive. I had not had to stand in line outside a government department at five in the morning, day after day for weeks and months on end, just in order to be able to submit my application for asylum. I had not had to spend many anxious months or years condemned to inactivity, living in a hall that had been repurposed as mass refugee accommodation and plagued by uncertainty as to whether I would ultimately be allowed to remain in the country. I had not had to undergo the difficult task of coming to terms with a society whose language and culture were totally alien to me, for I had learnt German as a child at school in Ethiopia and had familiarised myself with German customs and practices as a student.

Back in 1974, I was one of very few asylum seekers. In Frankfurt there was just one other refugee from Ethiopia who had been made stateless; in the whole of Germany there may have been around a dozen or so. Now I am one of many. In the environs of Frankfurt alone, there are 10,000 Ethiopian refugees, and throughout the world there are 2.5 million of us. My story ended well: after seven years as an asylum seeker in Germany I was granted German citizenship, and I think I have thoroughly integrated myself into German society. I was lucky something I repeat to myself every morning in great gratitude as a kind of mantra.

Nowadays, as we read daily reports of the streams of people who are on the run worldwide, and as we see the images of the convoys of pick-up trucks laden with people crossing the Sahara, we should always keep in mind one thing: each and every one of these people is an individual with his or her own destiny; with fears and hopes for a better and more secure future; and with the desire to someday be able, after having found a new life, to look back on the time when he or she was fleeing as a refugee and say, just as I did, I was lucky.

Asfa-Wossen Asserate

Frankfurt am Main, December 2017

INTRODUCTION

By David Goodhart

T his is an angry book with plenty to be angry about. When the author, Asfa-Wossen Asserate, claimed asylum in Germany in 1974 after the coup in Ethiopia, in which his politician father was murdered, there were only a dozen Ethiopians in the whole country. There are now about 10,000 in the Frankfurt area alone, where he lives.

The number of Africans trying to leave their countries to build a better life in the West is estimated at more than 1 million each year, excluding those fleeing war or natural disasters.

Why are they coming, or wanting to come, in such large numbers? Because too many African countries are not offering a future. Ethiopia itself produces about 35,000 graduates every year but only around 5 per cent find paid employment in the country. As Asserate says, if you take a room at the Sheraton Hotel in Addis Ababa the likelihood is the that maid who serves you coffee will have a bachelors degree to her name.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «African Exodus: Migration and the Future of Europe»

Look at similar books to African Exodus: Migration and the Future of Europe. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book African Exodus: Migration and the Future of Europe and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.