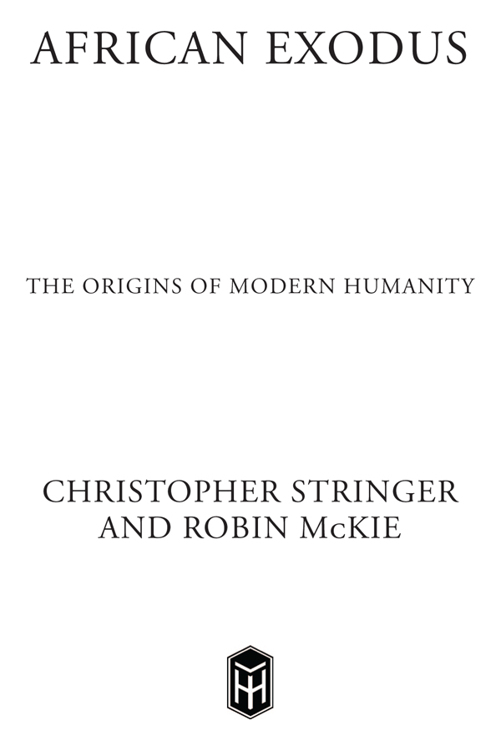

Chris Stringer - African Exodus: The Origins of Modern Humanity

Here you can read online Chris Stringer - African Exodus: The Origins of Modern Humanity full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2015, publisher: Henry Holt and Company, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:African Exodus: The Origins of Modern Humanity

- Author:

- Publisher:Henry Holt and Company

- Genre:

- Year:2015

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

African Exodus: The Origins of Modern Humanity: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "African Exodus: The Origins of Modern Humanity" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

African Exodus: The Origins of Modern Humanity — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "African Exodus: The Origins of Modern Humanity" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Thank you for buying this

Henry Holt and Company ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on Christopher Stringer, click here.

For email updates on Robin McKine, click here.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To our families

and our futures

Ex Africa semper aliquid novi.

(There is always something new out of Africa.)

Pliny the Elder

We would like to thank the friends and colleagues who have contributed to the discoveries and ideas discussed in this book, although they will not all agree with our conclusions. Yoel Rak, Jean-Jacques Hublin, Maryellen Ruvolo, and Walter Bodmer read chapters and provided helpful comments. Robert Kruszynski, Rosie Stringer, and Sarah Mitchell gave invaluable general help, and Irene Baxter patiently typed much of the manuscript. We would also like to thank all those who provided material for the illustrations, particularly Akio Morishima, Ian Tattersall, Barbara West, and the Photographic Unit of the Natural History Museum. Last but not least, we would like to thank the Natural History Museum and the Observer for their support.

For the past few years, a small group of scientists has been accumulating evidence that has revolutionized our awareness of ourselves, and our animal origins. They have shown that we belong to a young species, which rose like a phoenix from a crisis which threatened its very survival, and then conquered the world in a few millennia. The story is an intriguing and mysterious one, and it challenges many basic assumptions we have about ourselves: that races deeply divide our populations; that we owe our success to our big brains; and that our ascent was an inevitable one. Far from it: people on different continents are closer evolutionary kin than gorillas in the same forest; Neanderthals became extinct even though they had bigger brains than Homo sapiens; while chance as much as good design has favored our evolution. We can see evidence of this startling 100,000-year-old genesis not only in the bones of the dead, but in the genes of people alive today, and even in the words we speak. It is a remarkable, and highly controversial narrative that has generated headlines round the world and has been the subject of a sustained program of vilification by scientists who have spent their lives committed to the opposing view that we have an ancient, million-year-old ancestry. The debate, which reverberates in museums, universities, and learned institutions across the world, is one of the most bitter in the history of science. How these events came about and how we learned about our true nature, and our African Exodus 100,000 years ago, is explained by a scientist at the very center of the arguments and a journalist who has closely followed every twist and turn of this dramatic scientific story.

All great truths begin as blasphemies.

George Bernard Shaw

I have never been able to trace the source of my passion for fossils. Neither, to their eternal bafflement, could my family. Indeed, it was the basis for some unease that I spent so much of my childhood drawing and painting skullsscarcely a healthy hobby for a growing boy, after all. I was also famed (if that is the right word) in our family for asking, as a youngster on one of my frequent visits to Londons Natural History Museum, if the attendants could give me any old bits of skeleton they didnt need. Fortunately, their rebuff was of such gentleness that my ardor for ancient bones was left undented.

Indeed, such was my eagerness to spend my life among fossils that when I discovered it was possible to study human evolution as a special subject in its own right, I promptly discarded my dearly won place at medical school in order to devote myself to anthropology. The decision horrified my headmaster and my biology teacher, the latter concluding a sorrowful lecture with a prediction that I would never get a job doing that subject. My parents, to their eternal credit, suppressed their uneaseand backed my decision.

I have since had many reasons to be grateful for their support. My mother and father helped me to pursue a career which has involved me in one of the great scientific dramas of modern times: the unfolding of a radical new understanding of our birth as a species and about the source of what are commonly called racial differences. This new theory has, in turn, triggered one of the fiercest, most bitter debates about our originsa considerable achievement for a field already infamous for polemical divisions and open rivalry. As a result, I have been permitted to be both observer and participant in one of the great intellectual clashes of this century.

At the time of my introduction to the subject, however, I was merely concerned with trying to make a career in it. I graduated from University College London, still imbued with a love of the study of human evolution, and began to plan my Ph.D. research in 1969in an intellectual climate dominated by a widespread antipathy towards social science, an aftermath of the student troubles of 1968. In addition, none of the hard science councilswhich distributed cash for medical, scientific, or environmental projectswould take responsibility for research on fossil humans. The subject seemed to fall between all three. Despite the efforts of Michael Day (then at the Middlesex Hospital Medical School), Nigel Barnicot of University College London, and Don Brothwell of the Natural History Museum, I failed to raise the interests of any of these organizations.

By the summer of 1970, there were still no signs of a grant and my prospects of becoming a paleoanthropologist looked bleak. My biology teachers forebodings about my future occupation were beginning to look ominously prescient. Indeed, I was on the verge of giving up my temporary job at the Natural History Museum to go to a teachers training college when, at the last minute, a spare Medical Research Council post came up at Bristol Universitys anatomy department: for a student to conduct research on human evolution. Jonathan Musgrave, a lecturer at the department, phoned Brothwell, who gave him my name. Within a month I was on my way to Bristol.

Jonathan Musgrave had studied Neanderthals, that mysterious, sturdy lineage of human precursors who had lived, died, and been buried in the caves of Europe tens of thousands of years ago, and whose relation to our own species, Homo sapiens, underpins our understanding of ourselves and our evolution. In Musgraves case, he had analyzed their hand bones, using a technique called multivariate analysis that exploits mathematical methods for examining many measurements at once. Two or more different objectsa pair of skulls, for exampleare carefully surveyed, and a host of different measurements which mirror their shape are collected. Then, using the complex statistical methodology of multivariate analysis, it is possible to produce an overall measure of how much the two objects differ from each other. It is a powerful technique and I intended to use it on Neanderthal heads to determine just how similar they were to those of the Cro-Magnons, a race of early European members of Homo sapiens who thrived about 25,000 years ago and who were very similar to men and women today. As we shall see, this relationship is the source of considerable dispute among scientists today, for at its root lies the resolution of our own origins and nature. Did Neanderthals evolve into Cro-Magnons (and modern Europeans), or did the two represent distinct lineages or even species? I intended to bring an objectivenot an emotionalapproach to resolve these questions. I would use precise instruments such as calipers and protractors to determine skull height, breadth, and width; angle of forehead; projection of browridge; and dozens of other features to place Neanderthals and Cro-Magnons in their evolutionary context.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «African Exodus: The Origins of Modern Humanity»

Look at similar books to African Exodus: The Origins of Modern Humanity. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book African Exodus: The Origins of Modern Humanity and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.