This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books picklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1959 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2015, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

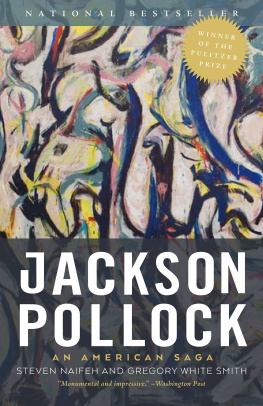

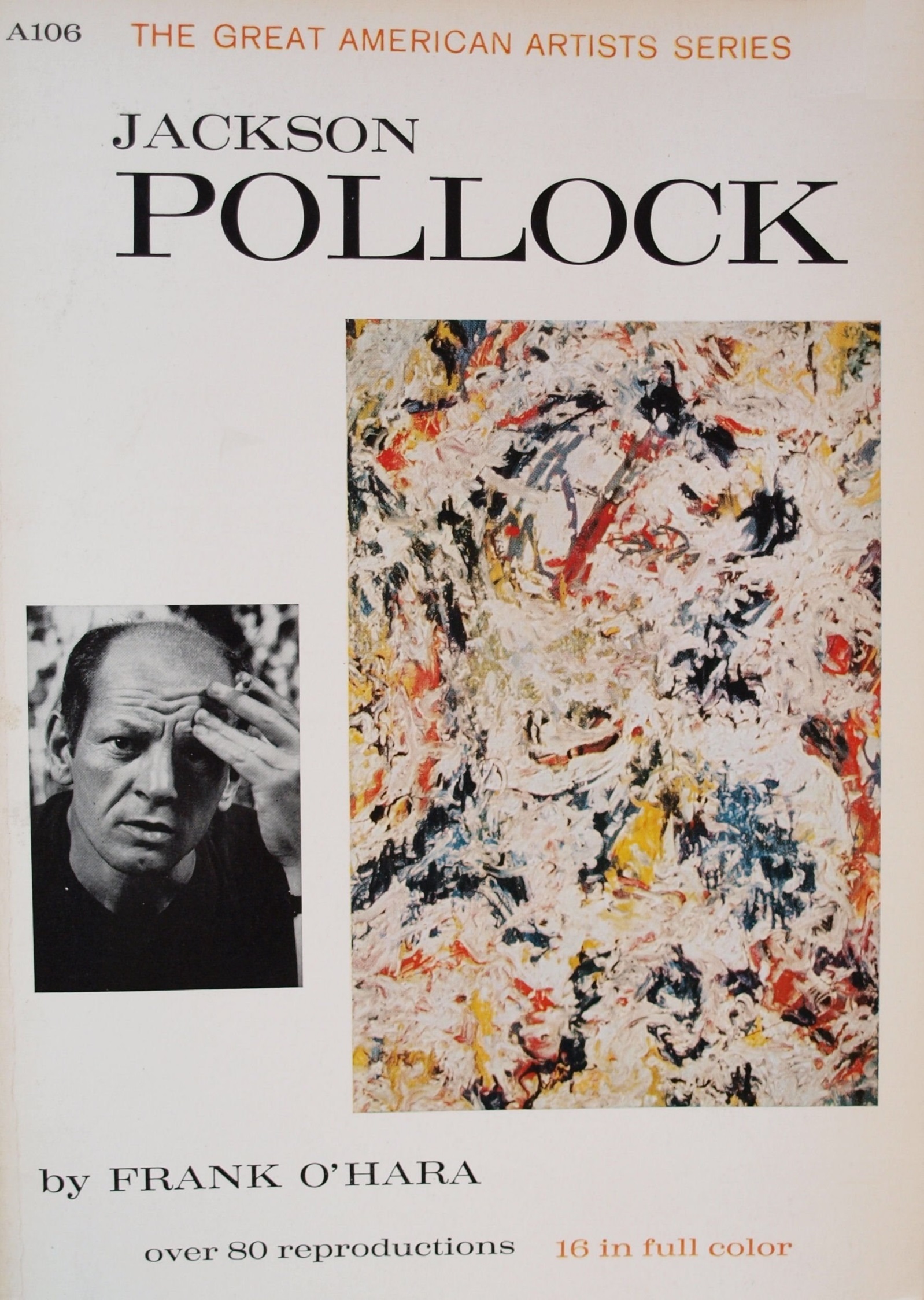

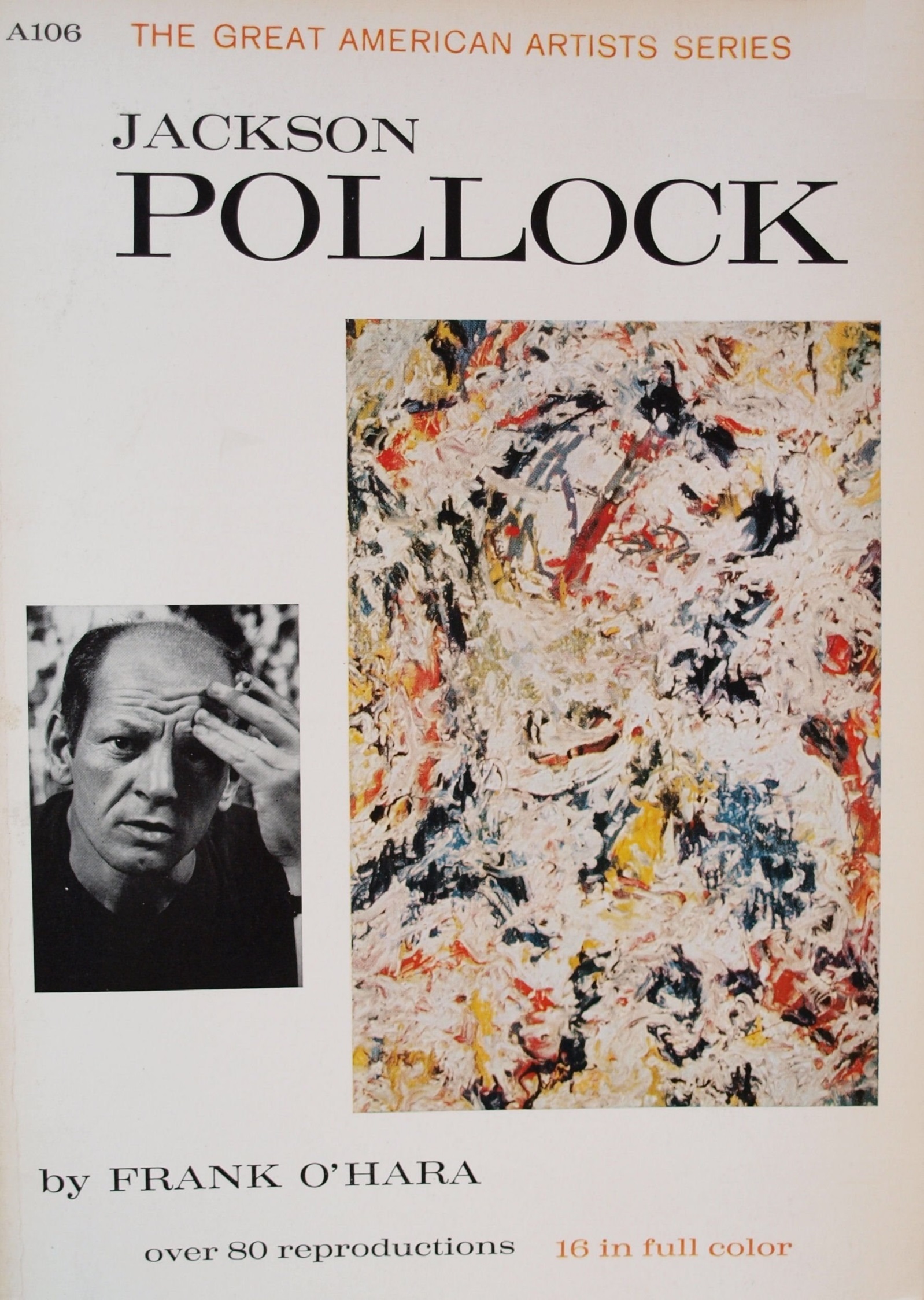

JACKSON POLLOCK

BY

FRANK OHARA

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

THROUGH THE YEARS of my acquaintance with Pollocks work I have absorbed, consciously and unconsciously, many of the insights of artists and friends, a debt which is difficult to acknowledge. I would like, however, to thank those whose help in assembling the present material on Pollock and his work, whether through conversation or critical writings, directly or indirectly, has been so great: Mrs. Lee Krasner Pollock, Clement Greenberg, Harold Rosenberg, James Schuyler, Robert Motherwell, Sam Hunter and Thomas B. Hess, to name only a few. It is to Grace Hartigan that I owe an awareness of certain aspects of Pollocks genius, and to Larry Rivers a particular appreciation of the beauties of Number 29 , 1950.

The brief chronology is based on those prepared by Sam Hunter for the catalog of the exhibition he directed at the Museum of Modern Art and by Clement Greenberg for Evergreen Review. The bibliography is based on material organized by Bernard Karpel, librarian of the Museum of Modern Art, for European catalogs of the exhibition of Pollocks work circulated in Europe by the Museums International Program.

Our thanks go also to the many public and private collections through whose kind cooperation we have been able to reproduce the works included in this book.

F. OH.

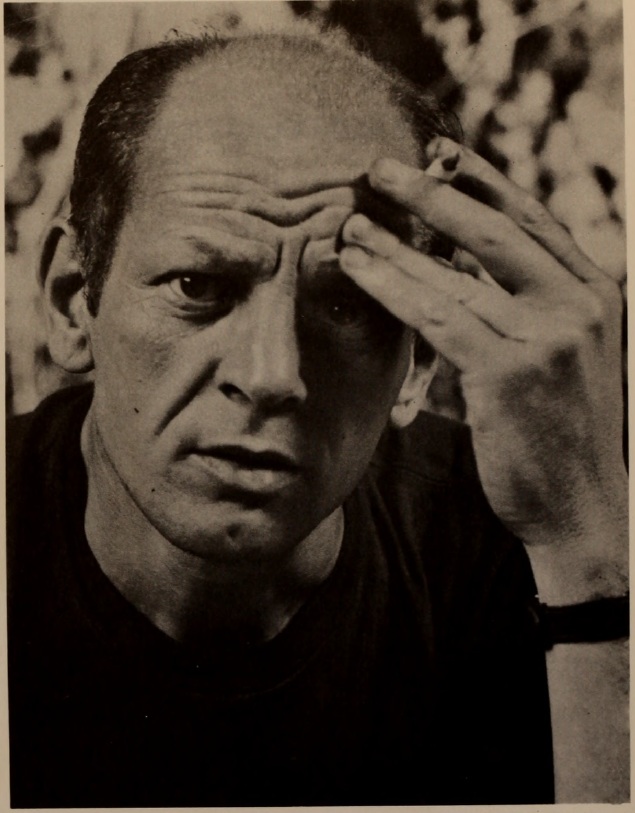

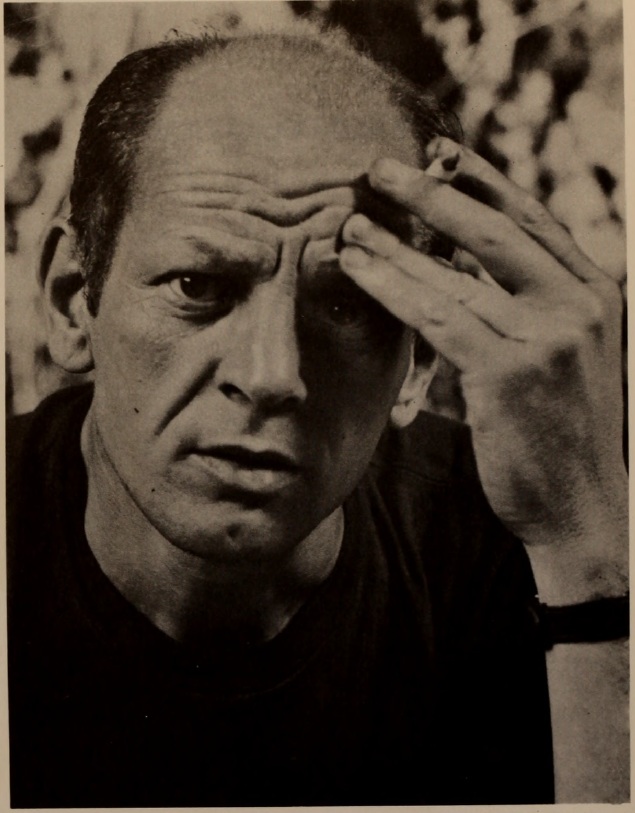

Photograph by Hans Namuth

JACKSON POLLOCK

Art is full of things that everyone knows about, of generally acknowledged truths. Although everyone is free to use them, the generally accepted principles have to wait a long time before they find an application. A generally acknowledged truth must wait for a rare piece of luck, a piece of luck that smiles upon it only once in a hundred years, before it can find application. Such a piece of luck was Scriabin. Just as Dostoievsky is not only a novelist and just as Blok is not only a poet, so Scriabin is not only a composer, but an occasion for perpetual congratulations, a personified festival and triumph of Russian culture.PASTERNAK, I Remember (Essai dAutobiographie)

AND SO IS Jackson Pollock such an occasion for American culture. Like the Russian artists Pasternak mentions, his work was nourished by international roots, but it was created in a nation and in a society which knew, but refused to acknowledge, the truths of which Pasternak speaks.

We note that Pasternak puts these general truths in the plural, for culture is capable of entertaining more than one truth simultaneously in a given era. Few artists, however, are capable of sustaining more than one in the span of their activity, and if they are capable they often are met with the accusation of no coherent, unifying style, rather than a celebration. Even Picasso has not escaped from this kind of criticism. Such criticism is panoramic and non-specific. It tends to sum up, not divulge. This is a very useful method if the truth is one, but where there is a multiplicity of truths it is delimiting and misleading, most often involving a preference for one truth above another, and thus contributing to the avoidance of cultural acknowledgment.

If there is unity in the total uvre of Pollock, it is formed by a drastic self-knowledge which permeates each of his periods and underlies each change of interest, each search. In considering his work as a whole one finds the ego totally absorbed in the work. By being in the specific painting, as he himself put it, he gave himself over to cultural necessities which, in turn, freed him from the external encumbrances which surround art as an occasion of extreme cultural concern, encumbrances external to the act of applying a specific truth to the specific cultural event for which it has been waiting in order to be fully revealed. This is not automatism or self-expression, but insight. Insight, if it is occasional, functions critically; if it is causal, insight functions creatively. It is the latter which is characteristic of Pollock, who was its agent, and whose work is its evidence. This creative insight is the greatest gift an artist can have, and the greatest burden a man can sustain.

The Early Works

Although Pollock is known as the extreme advocate of nonfigurative painting through the enormous publicity which grew up around his drip paintings of the late 1940s and early 1950s, the crisis of figurative as opposed to non-figurative art pursued him throughout his life. Unlike his European contemporaries, art for him was not a matter of deciding upon a style and then exploring its possibilities. He explored the possibilities for discovery in himself as an artist, and in doing so he embraced, absorbed and expanded all the materials which he instinctively reached for, and which we later find to be completely pertinent to the work. His method was inclusive: he did not exclude, from one period to another, elements in which he had found a previous meaning of a different nature. Thus it is that we find a relationship, however disparate in meaning, between the forms of the early Untitled, ca. 1936 (plate 3) and the Moon Vibrations of 1953 (plate 76), between the Untitled, 1937 (plate 5), which Sidney Janis has pointed to as perhaps the first of the radically all-over paintings later to be the preoccupation of a number of his contemporaries, and his own later all-over paintings, such as the Untitled of 1950 (plate 47) and the Frieze of 1953-55 (owned by Mr. and Mrs. Burton Tremaine, Sr.). So the figurative images of the great black-and-white period of 1951-52 relate to the numerous early drawings in which he changed the idioms of Picasso and Andr Masson into his own (naturalistic then) conception of space and incident. A good example of what he accomplished in the latter case, where space becomes the field of incident, may be seen in the White Horizontal , 1941-47 (plate 12), an accomplishment which Pollock did not dwell on, though the ramifications of what he found in doing it linger in his work and the work of others to this day.

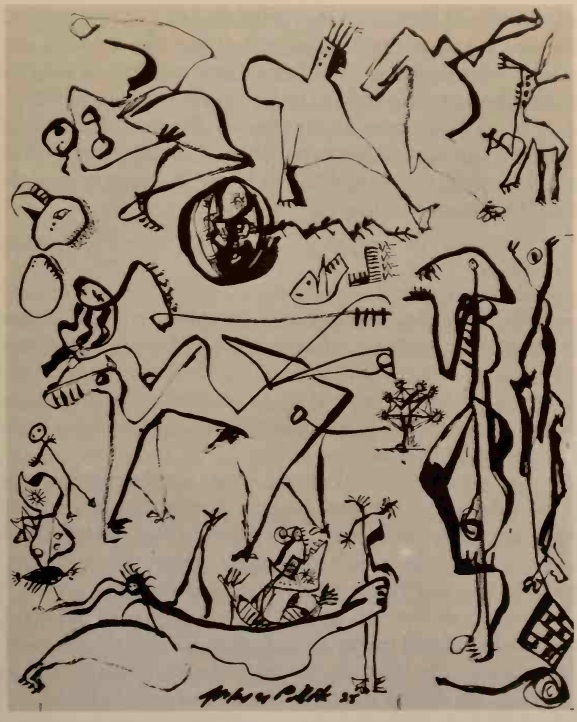

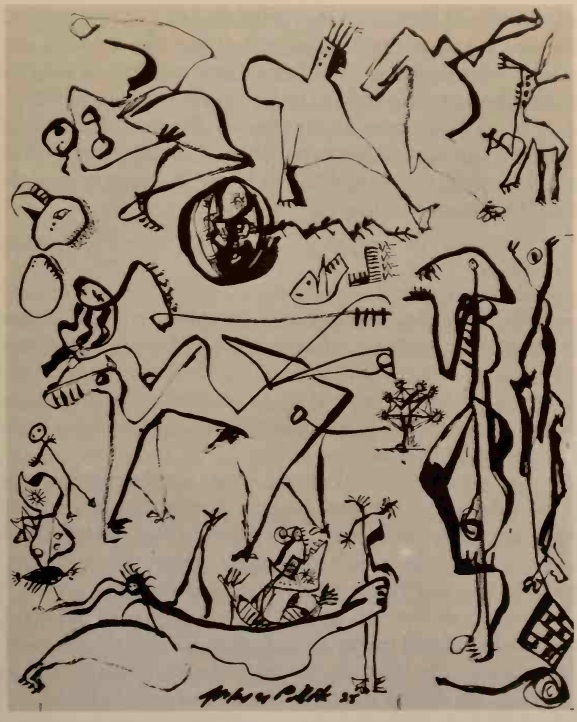

Drawing. 1938. Ink on paper, 17 7/8 x 13 7/8. Collection Lee Krasner Pollock

The Mexicans

Pollock, from the first, had quite apparently a flair for drama, in the sense of revelation through stress and conflict. His student period has been so well and thoroughly expounded by Sam Hunter in the preface of the Pollock exhibition he organized for the Museum of Modern Art in 1956, that a detailed retracing of his development would be repetitive.

Next page