CONTENTS

For Richard and Estie,

who made sure I did not get lost

PROLOGUE

OCTOBER 21, 1942

SOMEWHERE OVER THE SOUTH PACIFIC

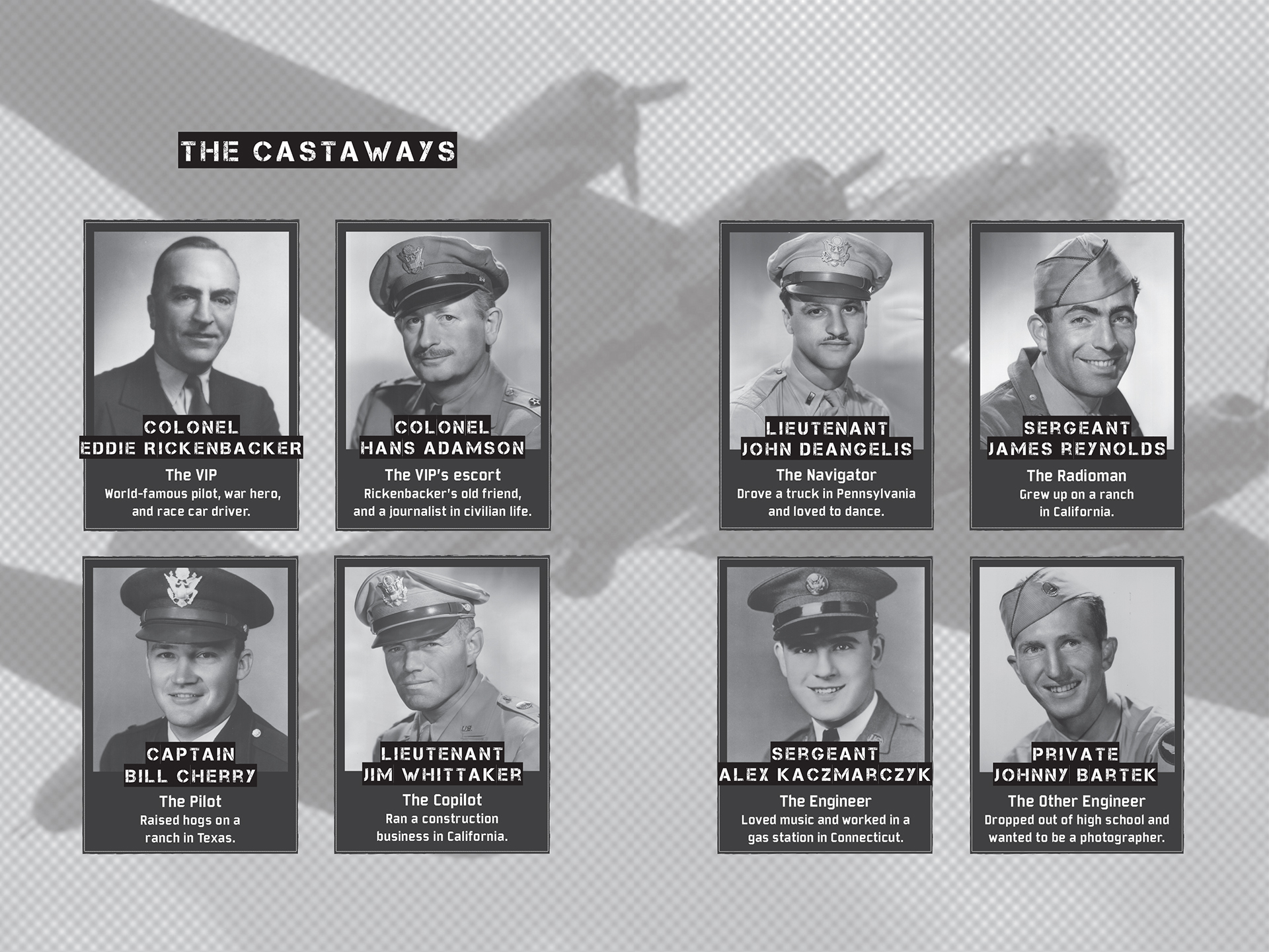

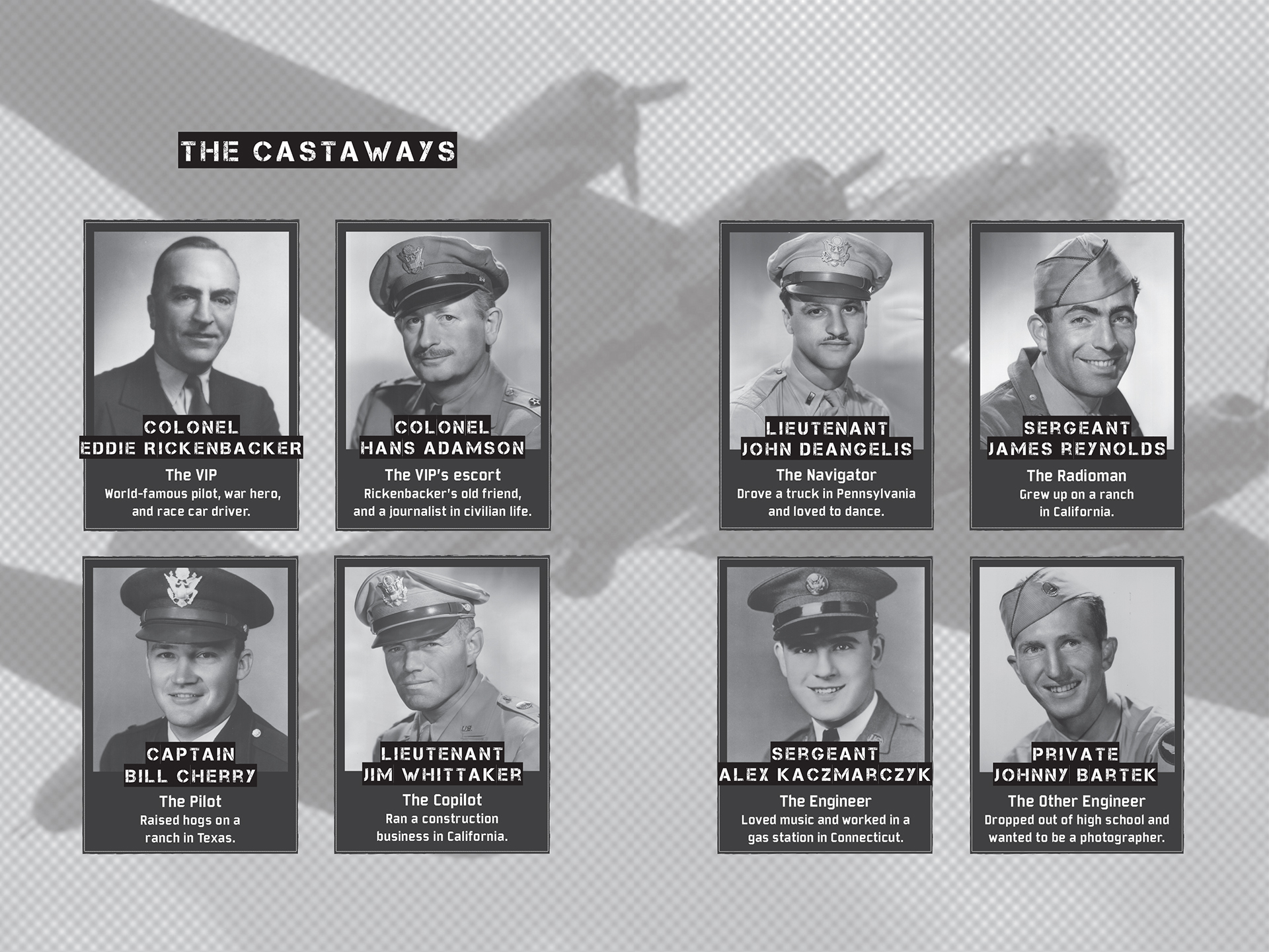

T he Pacific Ocean looked calm and inviting from 5,000 feet up, with the drone of four sturdy motors in Jim Whittakers ear. But he had no desire to land a 15-ton, 4-engine plane down there. To a B-17 bomber, plunging from the sky, the ocean is as unforgiving as a concrete wall.

Yet by 1:30 p.m. on October 21, 1942, that was the only option left. Whittaker was the B-17s copilot. He and the rest of the crew were ferrying a VIP passenger on a top-secret mission deep into the war zone. They had completely missed Canton Island, the tiny speck in the great blue where they were supposed to refuel. Now they were flying in a giant square pattern, hoping to spot land. They took turns staring out the windows at the ocean below, mistaking cloud shadows for islands. Island eyes, the airmen called itthe surest sign that desperation had set in.

The Plane: A 15-ton, 4-engine B-17.

The fact was they were lost, somewhere in the middle of the Pacific. They were nearly out of fuel, and the only landing strip they had was a vast tarmac of water.

No one knew exactly how they had lost their way. Maybe the tailwinds were stronger than the weathermen had predicted. Maybe the compass had taken a hit when they nearly crashed taking off in Hawaii. Either way, the navigator had finally given up trying to figure out where they were. He was a young guy named John DeAngelis who had gotten married just two days before they were called away. Now he was probably wondering if he would ever see his wife again.

Do you fellows mind if I pray? he shouted to the crew over the roar of the engines.

Pray? Whittaker thought. How about keeping your mind on the task at hand: surviving an impact with the Pacific Ocean.

Whittaker decided not to say a word. DeAngelis could swan dive into the ocean and it wouldnt matter. Their lives were in Bill Cherrys hands nowthe twenty-seven-year-old pilot from Texas who sat next to Whittaker with the controls in his hands.

Cherry and Whittaker began to talk strategy. It had been ten and a half months since the United States was drawn into World War II. In that time, plenty of bomber crews had ditched in the Pacific. Not one, as far as they could remember, had escaped without casualties.

If the surface of the ocean were flat, it would be one thing. But today, the water rose and fell in treacherous swells. If you came in across the current you would have to time it exactly right. Scrape the crest of a swell and the nose would dip, sending the plane plummeting to the depths. Avoid one crest and you could ram the plane into the next one, shattering the entire craft into pieces in an instant.

There was only one way to do it, Whittaker and Cherry agreed. Come in parallel to the swells and set the plane down in a trough. That, of course, was easier said than done. The troughs were a moving target, and the wind blew across your flight path, making it hard to hold a line. Hitting a landing spot just right would still take perfect timing, expert piloting skills, and a whole lot of luck.

While Cherry and Whittaker worked out a strategy, their top secret passenger took charge of the crew behind them. And if luck really had anything to do with their fate, maybe he would tip the scales in their favor. He wasnt some desk-bound politician or stuffy diplomat. The VIP on board was none other than Eddie Rickenbacker.

For anyone who cared about flyingand for most everyone elsethat was all the introduction he needed. Aside from Charles Lindbergh, he was the worlds most famous pilot. He hadnt flown in combat since 1918, when World War I ended. But to millions of Americans, his heroics against the Germans were unforgettable. He had shot down more enemy aircraft than any other American pilot.

The Ace: Rickenbacker in France near the end of World War I.

Now Rickenbacker was a businessmanpresident of Eastern Air Lines. But he had a well-known reputation for surviving close scrapes. He had first become famous as an auto racer, driving primitive cars at breakneck speeds. As a fighter pilot, he nearly had his plane shredded by German bullets several times. Then, in the spring of 1941, he had been a passenger on one of his own airliners when it crashed in a Georgia forest. Trapped in the wreckage, he managed to direct rescue efforts with broken ribs, a shattered elbow, a fractured skull, and an eyeball torn loose from its socket. He was in such bad shape that the famous radio commentator Walter Winchell reported his death on the air. When Rickenbacker heard it from his hospital bed, he picked up a water pitcher and threw it at the radio.

A year and a half later, Rickenbacker still looked frail from the crash and walked with a cane. But now, with another crash looming, he seemed determined to survive one more time. Rickenbacker grabbed the young sergeant, Alex Kaczmarczyk, and pried open the bottom hatch in the B-17s tail. Then he and Kaczmarczyk lightened the planes load to save fuel and lessen the impact when they went down. Out went the cots, tool kit, blankets, empty thermos bottles, and luggage. Sacks full of high-priority mail sailed into the wind, soon to be a soggy, unreadable mess of good wishes that would never make it to the soldiers on the front lines.

Cherry announced he was starting his descent, and the water outside Whittakers window looked more distinct by the second. Back in the radio compartment, the men piled essential provisions by the hatch: a few bottles filled with water and coffee; emergency rations in a small metal box; a two-man raft rolled into a tight package. Once they landed, they might have as little as thirty seconds to get out before the plane went underassuming they were still alive.

The men stacked mattresses in position, padding the aft, or rear, side of the walls that separated the compartments of the plane. They all took their positions. Three menKaczmarczyk, DeAngelis, and Rickenbackers military escort, Colonel Hans Adamsonlay on the floor, braced against the mattresses. Rickenbacker sat near them, belted into a seat near a window. Johnny Bartek, the engineer, sat just behind the cockpit. The plane had two inflatable rafts packed into compartments on the outside of the nose. It would be Barteks job to release them just after they ditched. James Reynolds, the radio operator who went by Jim, sat at his desk in the center of the plane. He tapped out SOS after SOS, hoping that someone out there would register their location before they hit the water. There was nothing but silence from the other end.

How much longer? someone asked.

Not yet, Rickenbacker answered, peering out the window.

In the cockpit, the altimeter showed they were 500 feet above the sea. Cherry cut two of the engines to save fuel. Whittaker grabbed cushions from the seats behind them and stuffed them under their safety harnesses.

Its sure been swell knowing you, Bill, he said, offering his hand.

Next page