The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

If sorrow settles in your heart, then where is the home of joy?

The sorrows and joys of life are all mixed together.

No one can separate them, except the One who created them.

Real men do not die of death; death finds its death in man.

Real men do not die of death; death finds its name in man.

When a mans name is respected, then death has no name.

My grandfather said

Contents

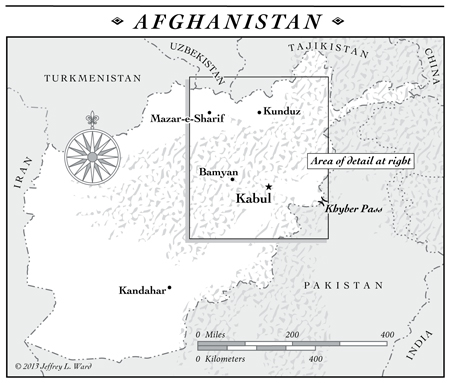

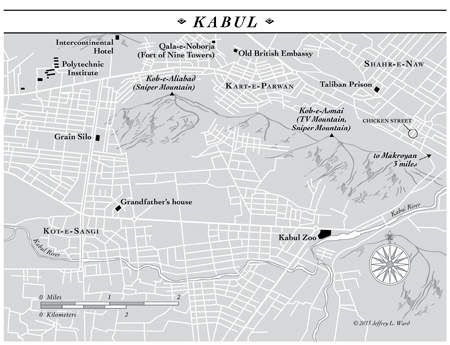

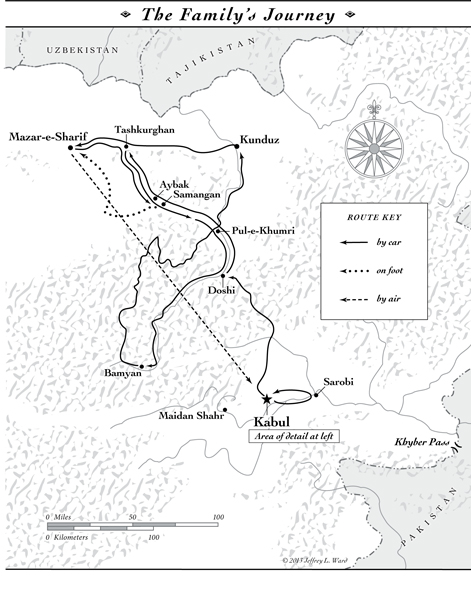

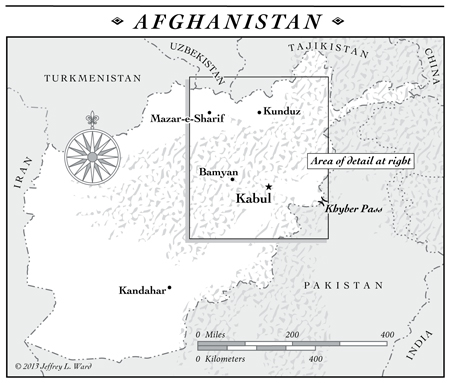

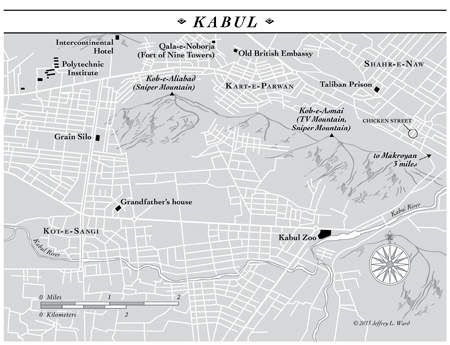

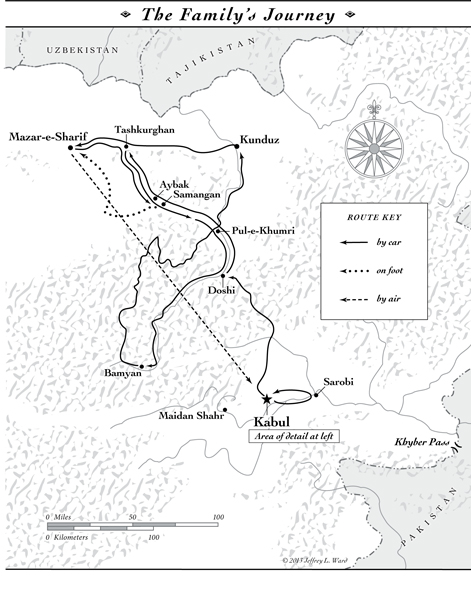

MAPS

Prologue

The calls always come early in the morning. Sometimes I am still praying when I hear my mothers phone ring upstairs. I lean forward and touch my head to the carpet and make an extra effort to focus on the ancient verses streaming through my mind.

Alla-hu-Akbar. Subhanna rabbiyal Aala

Even before my mother answers it, I know who is calling.

It is my aunt, in Canada. She has just come home from a wedding party where she met a family with a daughter, a beautiful girl, very intelligent, and funny. A very good family. They are from Kabul, or Kandahar, or Mazar-e-Sharif, and our grandfather knew their uncle, or her father went to Habibia High School with the cousin of our neighbor who used to manage the Ariana Hotel before it was destroyed, or

Qul Huwa All hu 'A adun, All hu A - amadu, Lam Yalid Wa Lam Y lad, Walam Yakun Lahu Kuf an 'A adun.

My aunt has been in Canada for thirty years. I think she knows all the other Afghans there. She helped many of them when they first arrived, even though she herself was a young widow with a small daughter in a strange land whose language she struggled to master. Afghans never forget a kindness, though. Now, everywhere she goes, she is welcomed by those she helped and respected for the kindness in her heart. Almost every week, except during Ramazan, she is invited to a wedding.

Weddings are where my aunt tracks the young women whom she has known since they were babies. She has watched them become young women, and seen them taking full advantage of opportunities they would never have had in Kabul had their families stayed there over the past three decades. Through it all, she has kept a list of future husbands for them in her mindnephews, neighbors, sons of former students from her days as a teacheralways waiting for the day when she can be of help.

Inn a ayn ka al-kawthar, Fa- alli li-Rabbika wan ar, Inn shaani-aka huwal abtar.

I am twenty-nine years old. I have a university degree. I run my own carpet business and sometimes work with the foreigners. I have both arms and legs, which is an issue in mine-ridden Afghanistan. I come from a good family and am not yet married. I am a Pashtun with Hazara eyes thanks to a great-great-grandmother whose name no one remembers because she was a woman, and who was from some Central Asian tribe with Mongolian roots. I am the embodiment of this world-spanning mixture of peoples we call Afghan.

I give my aunt a reason to go to weddings on the nights she is tired, or when the snow is deep. I give her something to talk about, and someone to boast about. I sell carpets. She sells me. Her great hope is that I can live someplace where I can prosper and be safe.

How do I tell her, then, that though it sounds mad, I love Afghanistan? That I love being an Afghan? That I want to help rebuild what so many others destroyed? I know it will take a long time. I understand that. I am a carpet weaver. I know how, slowly, one knot follows another until a pattern appears.

Oh, God, can you not weave my destiny to keep me close to these people who mean more to me than any others in the world?

Ameen .

* * *

When I finish my prayers, I sit near the tall windows that look down over Kabul University and to the mountains beyond. The dust is so thick even at this early hour that I can hardly make out the outlines of the jagged peaks against the dawn.

Kabul has become a very dusty place. How many million people live here now? No one knows. When I was young, there were only eighty thousand of us. A big town with big houses that had big gardens. Now we live on the side of a mountain, like goats, on land sold to us by a squatter.

The sun rises from behind the mountains and burns through the dust with a greasy glare. I lean back on a cushion that was made by nomads who travel each year across miles of arid land in search of a patch of grass for their flocks. My people were nomads until my grandfather settled in Kabul. We have no livestock now, unless you count the cat on the roof.

My youngest sister brings me a thermos of green tea and the news that our aunt has called from Canada. I do not let on that I had already guessed that. I do not want to spoil her excitement at telling me. She has a devilish glint in her eye. I know she wants to make a joke about the girl my aunt was describing. By now, of course, my mother has given all the details to my four sisters who still live at home. My older sister, who is married, will hear everything before long. Marriage discussions in Afghanistan are a family matter, and a major source of entertainment. My youngest sister is trying to decide whether I am in the mood for jokes, or whether I will just send her away.

In the end, she walks off giggling to herself. If I ever leave this place, I will miss her more than I can bear to think about.

Sometimes I wonder whether it was difficult for Grandfather to leave the open lands of his nomad days for the confining walls of the city. I think of my teacher, Maulana Jalaluddin Mohammad Balkhi, known to the world as Rumi. He had to flee our country when the greatest teacher of our warlords, Genghis Khan, swept across our land, destroying everything.

* * *

It is time to go upstairs for breakfast. My father has already ridden off on his bicycle to teach his high school physics classes. My mother is preparing to go to her office where they coordinate relief for natural disasters. My two youngest sisters are leaving for school, adjusting their white headscarves over their black uniforms as they go out the door and head down the hill.

One of my other sisters has laid out some yogurt and fruit for me in the kitchen. She is studying agriculture at Kabul University and will soon go for her classes. My only brother, who is eight years younger than I am, is doing exercises in the room above me, sending down tiny clouds of dust as he skips a rope.

These are the things that happen every day. These are the rhythms of my family in the morning. These simple things will stay with me always; that is the one thing of which I am sure.

* * *

Uncertainty hangs thick like the dust in the air. I cannot see where the path of life will lead me. It is not my nature to sit and wait for something to happen. For the moment, though, unable to look forward, I have settled for gazing backward, to chronicle what I have witnessed in these few strange and turbulent years I have known.