Family of Earth

This book was published with the assistance of the William R. Kenan Jr. Fund of the University of North Carolina Press.

2016 James Rorex Stokely III and Dykeman Cole Stokely

Foreword 2016 Robert Morgan

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Designed by Richard Hendel

Set in Utopia and Bodoni Oldstyle

by codeMantra, Inc.

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

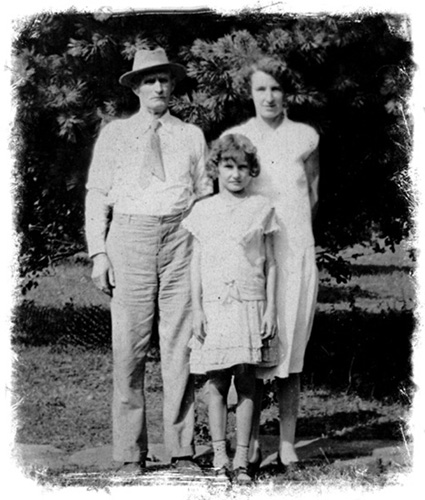

Cover illustration: Wilma Dykeman and her father on the back steps of her birthplace, about 1922. Photograph courtesy of Jim Stokely.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Dykeman, Wilma, author. | Morgan, Robert, 1944 writer of foreword.

Title: Family of earth : a Southern mountain childhood / Wilma Dykeman.

Description: Chapel Hill : The University of North Carolina Press, [2016]

Identifiers: LCCN 2015049261 | ISBN 9781469630540 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469629148 (pbk : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469629155 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Dykeman, Wilma. | Authors, AmericanNorth CarolinaBiography.

Classification: LCC PS3554.Y5 Z46 2016 | DDC 813/.54dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015049261

Contents

A section of photographs begins on page

Foreword

AFTER WILMA DYKEMANS DEATH in December 2006, her son, James Stokely III, searching through papers in her house in Newport, Tennessee, found a box labeled Northwestern. Under material relating to Dykemans graduation from Northwestern University in 1940, he discovered a two-hundred-page memoir which the author had either lost or forgotten. It would appear the manuscript was written during World War II, when the author was in her early to mid twenties, probably after the return to her native Asheville, North Carolina. This memoir, Family of Earth, adds significantly to her legacy of fiction and nonfiction. It is clear that from the first Dykeman was a very accomplished writer.

Wilma Dykeman (May 1920December 2006) belonged to a second generation of gifted Southern and Southern Appalachian writers, following the literary renaissance of Faulkner, Thomas Wolfe, Eudora Welty, James Still, Margaret Mitchell, Erskine Caldwell, among others. Along with Mary Lee Settle, Harriette Arnow, John Ehle, she furthered and deepened the literary heritage of the Southern Appalachian region. In both fiction and nonfiction, in workshops, lectures, classes at the University of Tennessee, in reviews and newspaper columns, she enriched the cultural life of the region for half a century. And with her husband, James Stokely Jr., she played a significant part in the discussion of the social, environmental, and racial issues of her time.

For those of us who have known Dykemans work for decades, and for those just discovering her fiction and nonfiction, the memoir Family of Earth is a treasure. Here we encounter an unusually gifted and observant young writer, exploring her voice, meditating with eloquence and lyrical passion on her life and family and the world from which she came. The writing is alive, with a fresh sense of wonder. The detail is intimate, sensuous, sometimes cinematic. In this memoir there is a special sense of thresholds connecting the past, the traditional, with the modern present.

The two themes that stand out in the memoir are the closeness to the natural world of trees, streams, butterflies, flowers, and the progress of the seasons and the closeness to family and a great variety of other people, including Aunt Maude, the Preacher, Old Man Milligan. As the author says on page 10, The life of one human is the life of every other living thing on earth.

It is thrilling to watch the young Dykeman explore the fresh papyrus of memory (11). The narrative reveals an unusually intense recall of infancy, the discovery of the self as a triumph of lone splendor (16). The truth is Wilma Dykeman was a poet as well as a prose writer, evoking the rumble of stones in a flooded stream, moments of hush, the many varieties of wildflowers, the Aladdins lantern (38) of childhood imagination, the death in nature that feeds life, the beauty of forest fires, butter making, tent caterpillars, dirt-daubers and katydids, hounds baying on the mountain, a rooster crowing in the middle of the night.

On page 37 Dykeman says, I do not believe that any true realist... can help being a romantic. Yet for all the romance and magic in her memories, there is a great deal of realism also as she recounts the pain of the Land Boom collapse in Asheville and the Great Depression, the leanness of mountain children, the loss of childhood imagination, the hurt of missed connections with those we know and love. The portrait of her father and the account of his illness and death are especially poignant.

In this early work Dykeman does not turn away from the tragic, the harsh, the essential loneliness of the human condition. She admits to a sense of not fitting in, either in the mountain community or in the society of Asheville, caught somewhere between two worlds and not belonging wholly to either. At dance lessons she feels like an intruder. Her social conscience is awakened when she realizes that sometimes when one gained, somebody, somewhere paid a price (98).

On page 95 Dykeman writes, I had no talent for boredom, which can serve as the theme of this memoir and all her writing. This long-lost book is her testimony of tast[ing] the fire (118) of poetry and the world around her. She speaks of an infinite curiosity for history, biography, for gardening and the rhythms and routines of the natural world, for travel, for exploration of solitude, for the singularity of my home-life (80). Her words serve as both telescope and microscope, making the distant in time close, enlarging the minute fact until it is luminous.

MY FIRST ENCOUNTER with the writing of Wilma Dykeman was with her nonfiction classic The French Broad. Reading that book was an important event in my discovery of the history of the Southern Appalachian region. The French Broad is such a vivid book and such a loving book, packed with information and insight, memorable writing, environmental consciousness. It gives us a living sense of the land, the watershed of the French Broad, the geology and geography, the Cherokee Indians, and the development of the culture of the area.

If I had to choose one image from The French Broad (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1955) to illustrate what inspired me most, it would be the motif of springs. Dykemans description of the headsprings of the river, and the importance of springs to the people, thrilled me and helped me remember much about my own familys spring. I had grown up drinking from and looking into springs: The cold sweet springs of these mountains... which feed with thousands of steady streams to make a river, have been valued for generations by the families they feed. If halfway up a hillside or deep in the heart of some remote cove you see a house and wonder why its people built there rather than on easier slopes, the answer is probably their water. Cupped in a clear steady pool under a thicket of blackberry vines and old shade trees, their spring bubbles from the earth like a rare gift for the taking (1112).

A little later, when I read her fiction, I made equally significant discoveries about Western North Carolina and about writing. I saw that the inevitable focus of fiction about the region was on the land and the seasons, and the strong women who struggled on the land to raise children and feed large families, to keep families together over the generations, through wars and natural disasters, sickness and poverty. There could be no better model for a young writer than Dykemans first novel,

Next page